Yan Krymsky and the Process of Placemaking

Yan Krymsky sits in his home office surrounded by bookshelves that stretch far past the lens of a webcam, the whole space drenched in the strong, slanted California morning light. The architect moved to Los Angeles, California from the seaside city of Odessa, Ukraine when he was a child. Since then, he’s fallen in love with his adopted metropolis and the effortless suave of America’s west coast. From childhood to university to Perkins&Will, Krymsky has called the City of Angels home for over 40 years, observing an influx of new residents as the city continuously takes on new types of civic challenges. “It’s a socially complex city, vast and difficult to really get to know, but it still retains a little of that wild west spirit. It’s easy to see why some of the icons of Modernism moved, worked and thrived here.” With his knack for imbuing projects with impactful stories, and a distinctly inclusive design ethos, Krymsky is using his vision to create places that tell stories as diverse as the city itself.

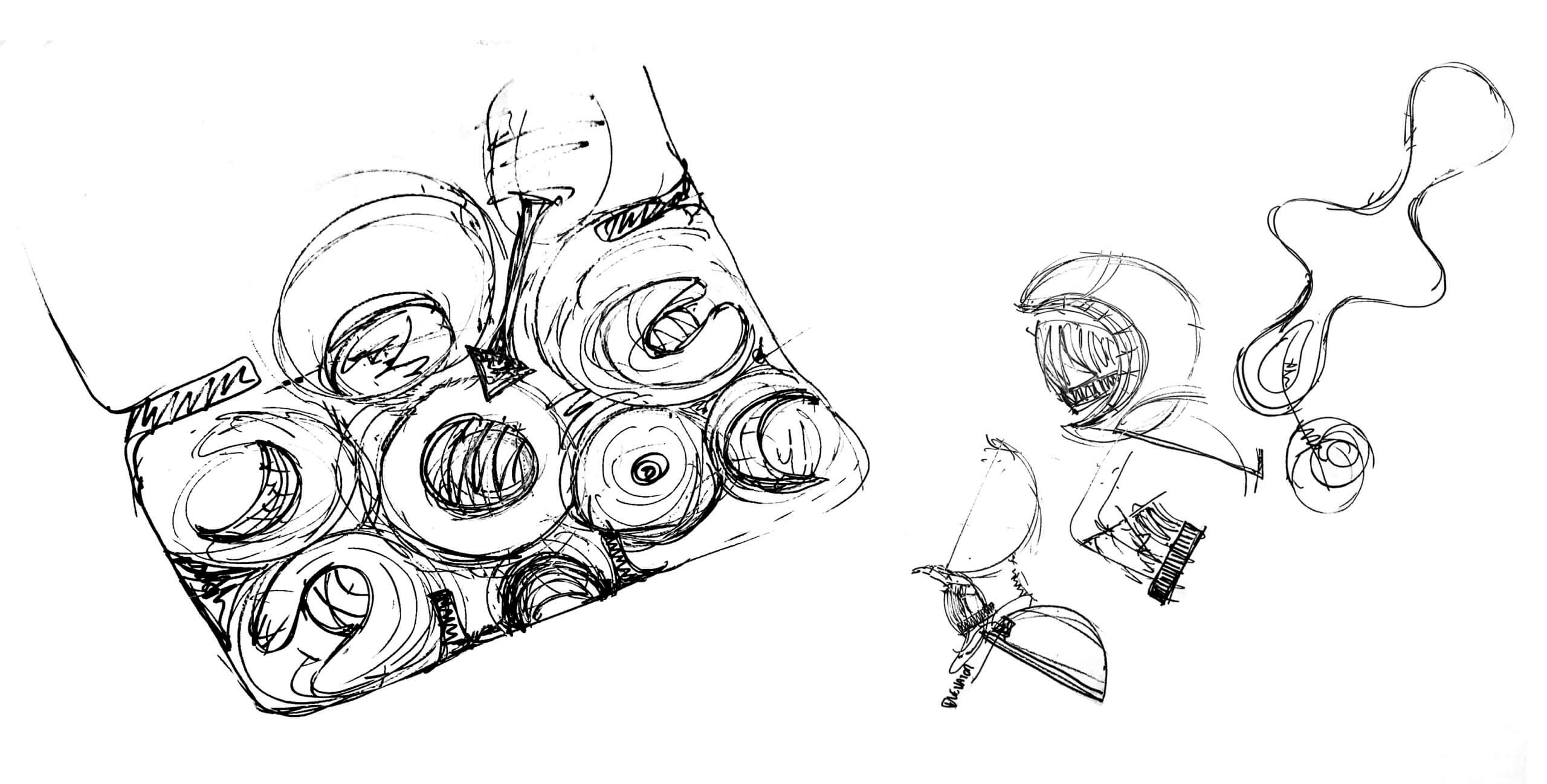

Krymsky’s passion morphed from an original interest in art into an aptitude for architecture, and eventual admission to the University of Southern California’s (USC) architecture program. He immediately found inspiration in the Los Angeles design community, and in the culture it fostered. “Soon after arriving at USC, I became enamored with the process of making, and communicating my thoughts through the meditative practice of imagining place,” he says. “It made all of my other subjects more vital and interesting, and that’s why I’ve stayed with it my entire life.”

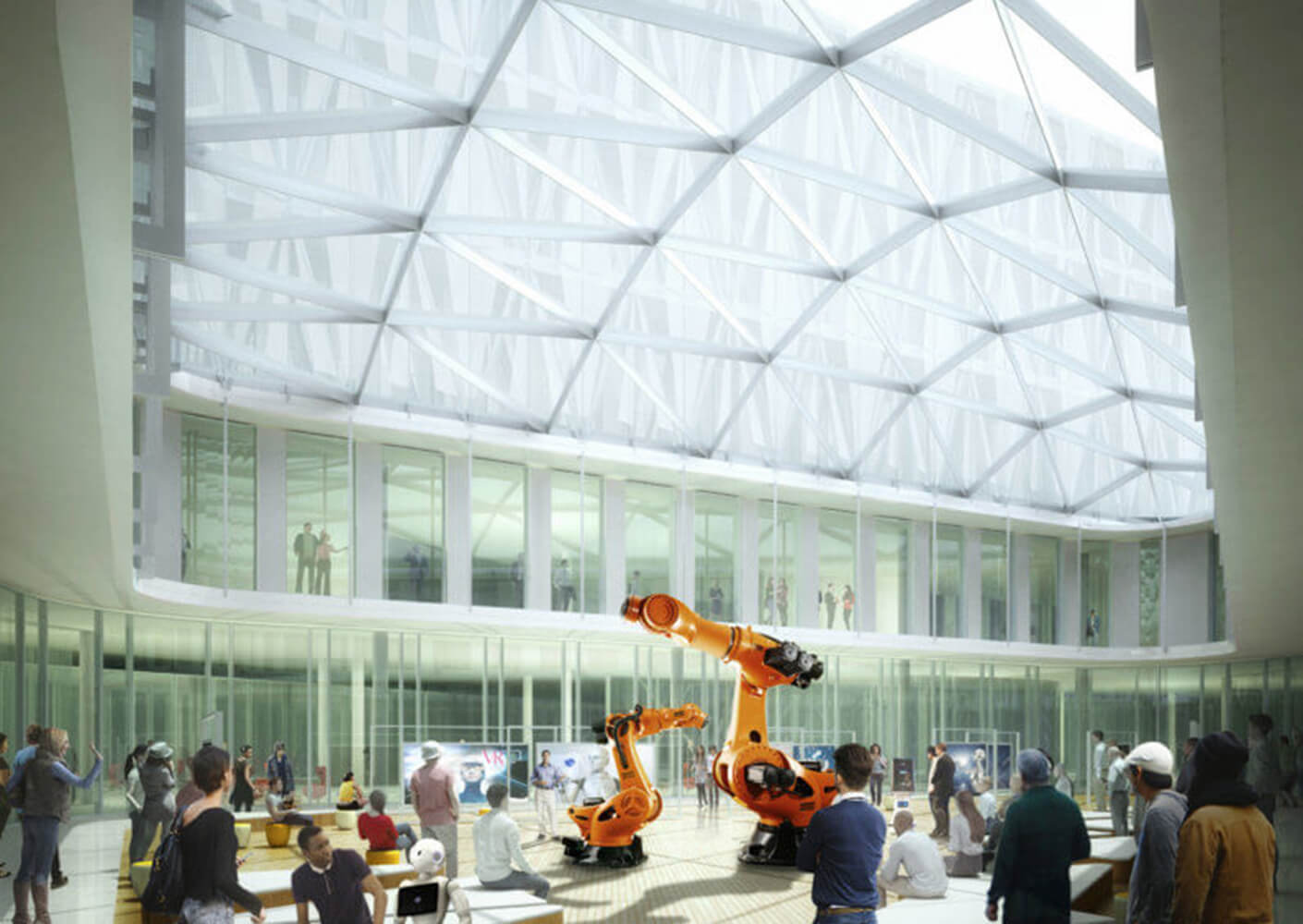

As a first-generation American, Krymsky has made a commitment to engage socially conscious work, saying that the alignment feels “natural.” Through his work as a design director, he has strived to dismantle the myth that one must ‘earn’ the right to access good design, as a luxury reserved only for the wealthy and impractical for everyone else. LA has a well-documented housing crisis, rooted in generations of planning for the traditionally White, single-family home model. But in a city where everyone has a “bubble”—delineated at times by a highway or a racially-segregated neighborhood. Krymsky is interested in popping them: “Every day, I think about taking design to places where it has not historically been,” he says, delivered with a voice full of passion and drive, yet soft around the edges. His natural leadership style allows his clients, collaborators, and team members alike feel more at ease.

Krymsky’s confident demeanor, coupled with a wealth of local experience, allows him to pull back the curtain on some of LA’s most urgent social issues. Both the designer and his home studio are at the forefront of J.E.D.I.—justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion—efforts in the profession and the community at large. “NIMBY was practically defined in this city,” he says, referring to “Not in My Backyard,” a colloquialism for resident-driven opposition to new, socioeconomically inclusive projects. “We’re so diverse, but not so integrated. This is something our LA studio is actively addressing in all our work, from social housing initiatives that creatively address the housing shortage here to blue-sky transit planning that would effectively and sustainably connect the next generation.”

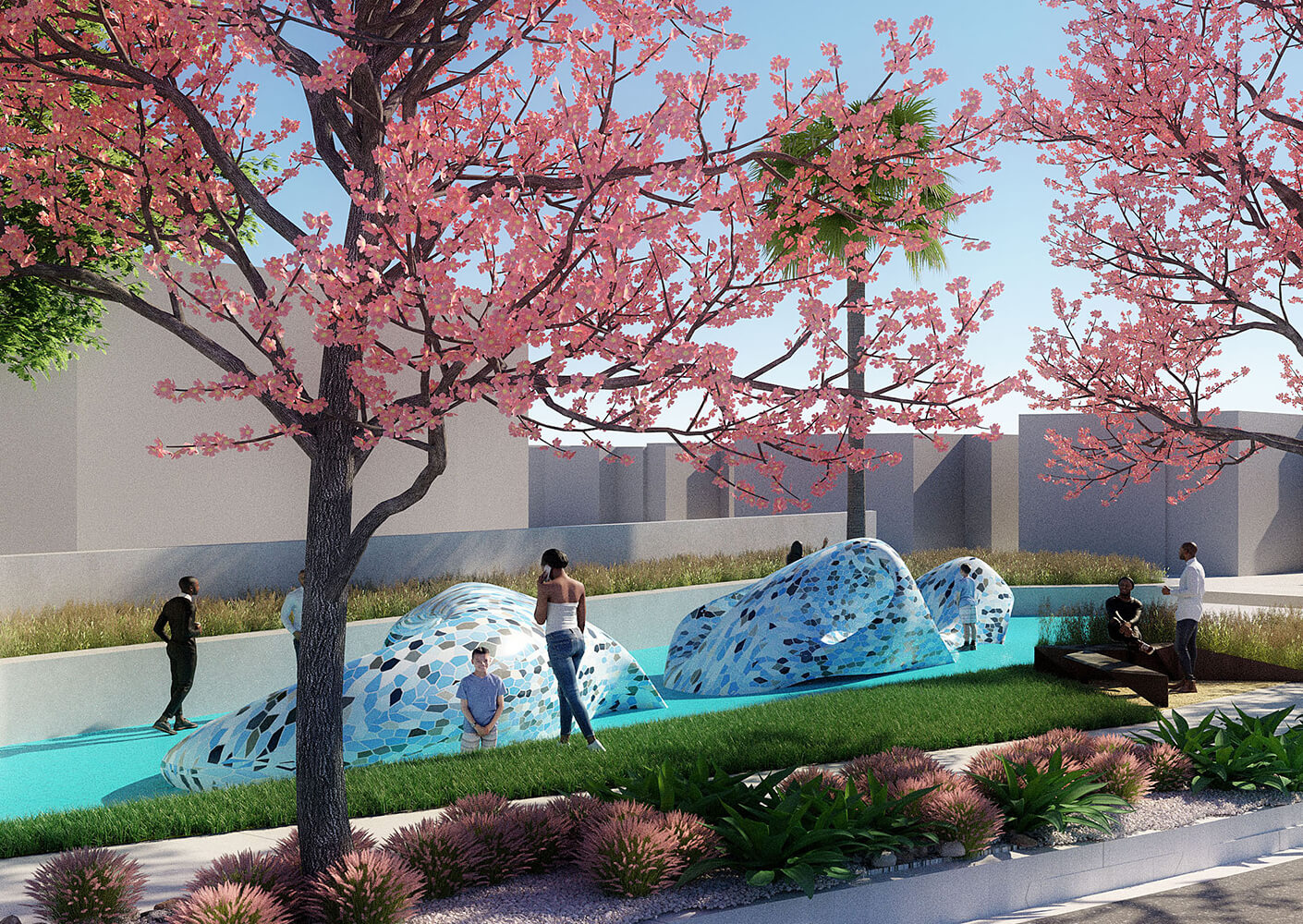

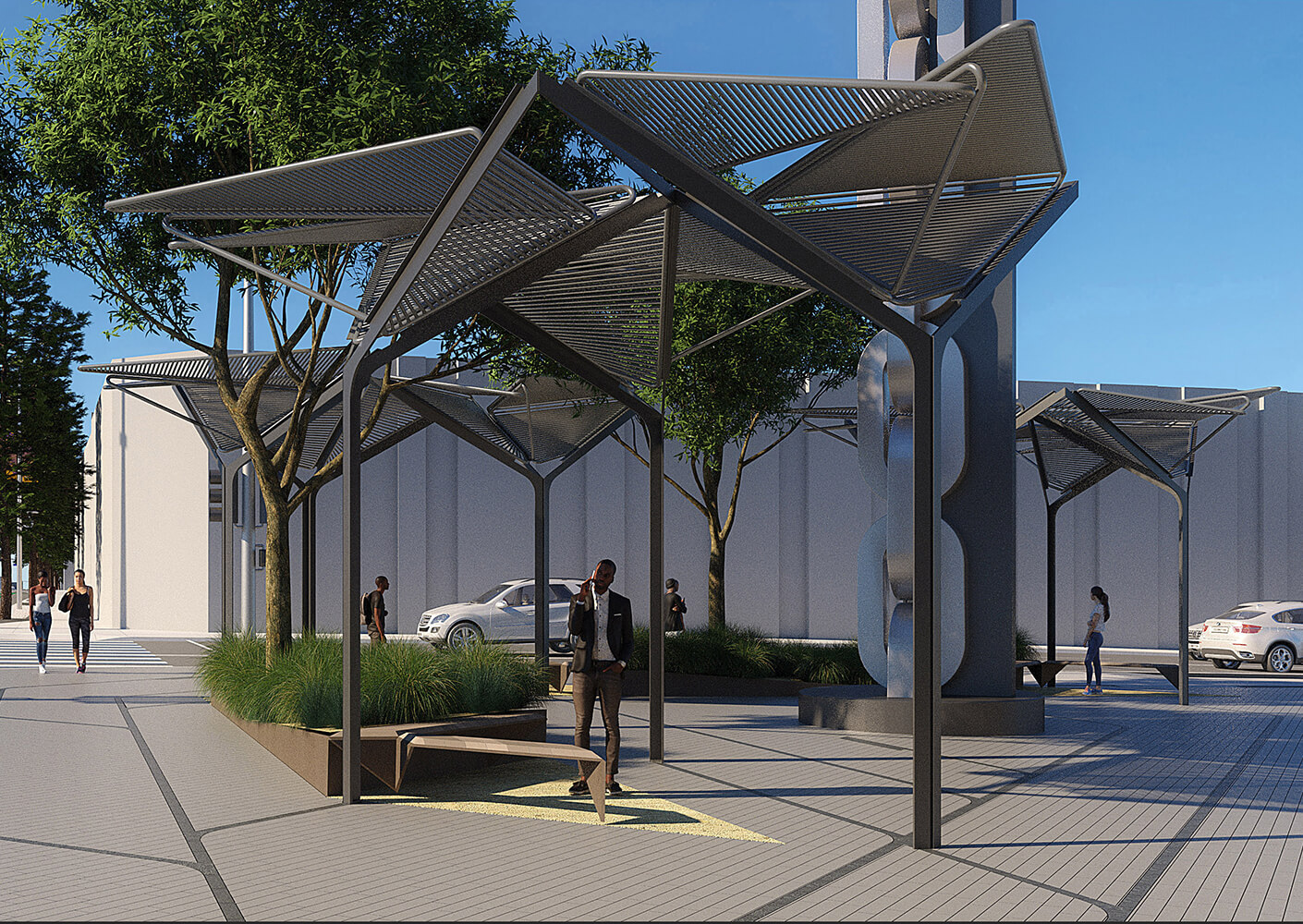

The LA studio is also the home base of Perkins&Will’s director of global diversity, Gabrielle Bullock. Both champions of J.E.D.I. in the design industry and our world’s cities, the two have collaborated on several projects that demand high cultural competence, notably Destination Crenshaw, a 1.3-mile-long outdoor gallery highlighting the arts and cultural contributions of the African American community.

Destination Crenshaw resonated with Krymsky not only for its social mission, but also because of the socially responsive narrative embedded in its design: There is a common symbolism, and true cultural relevance expressed throughout the place.

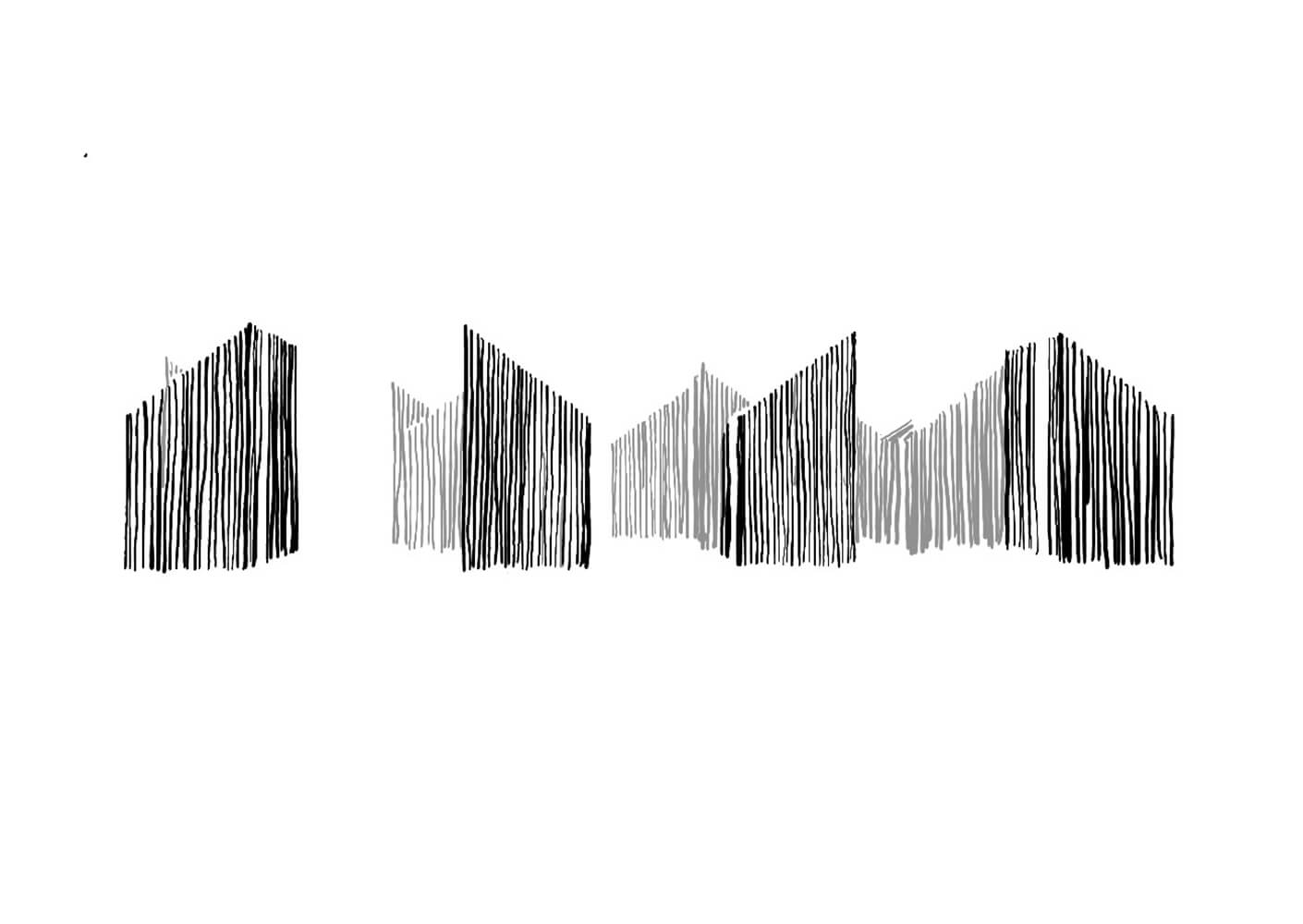

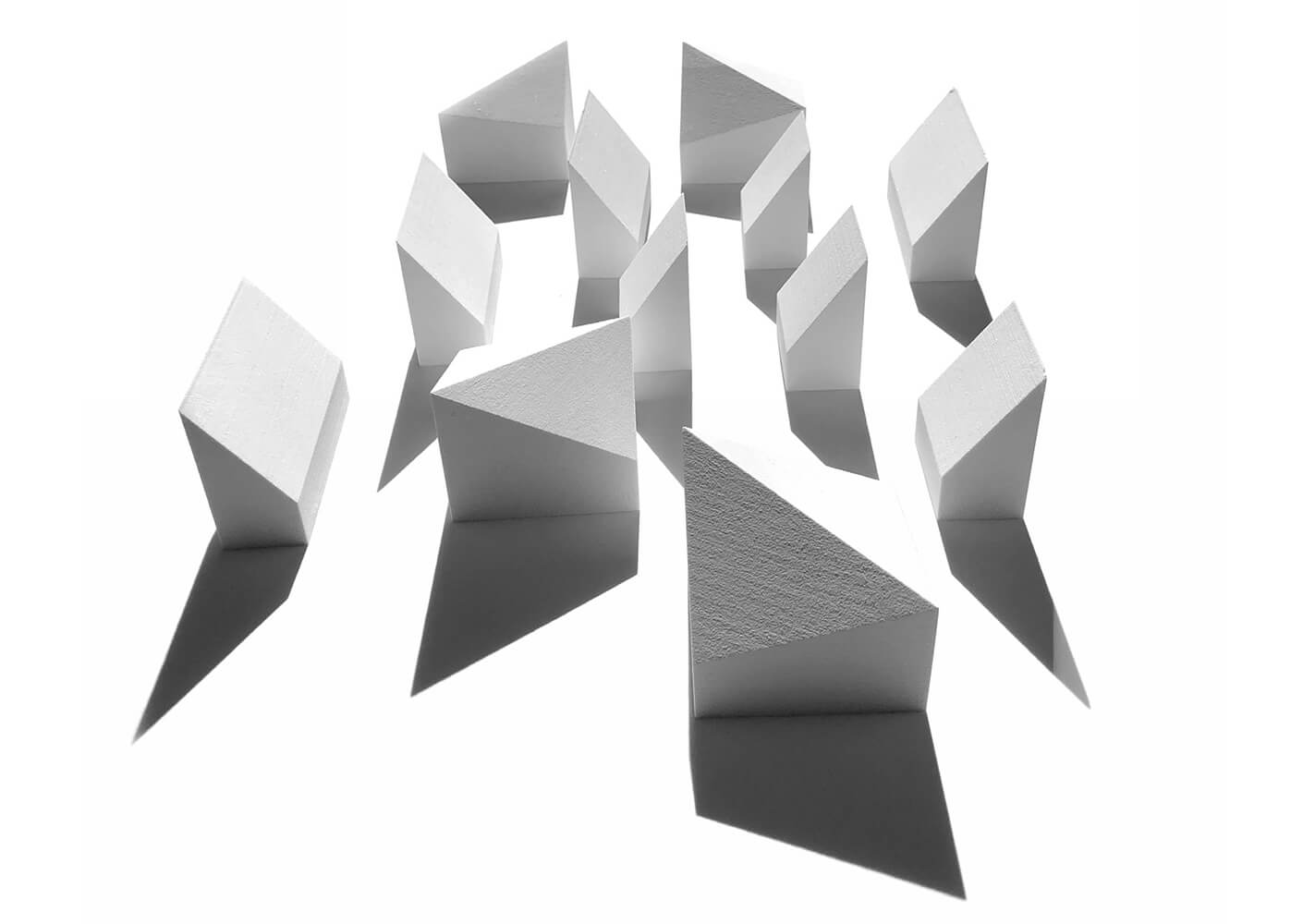

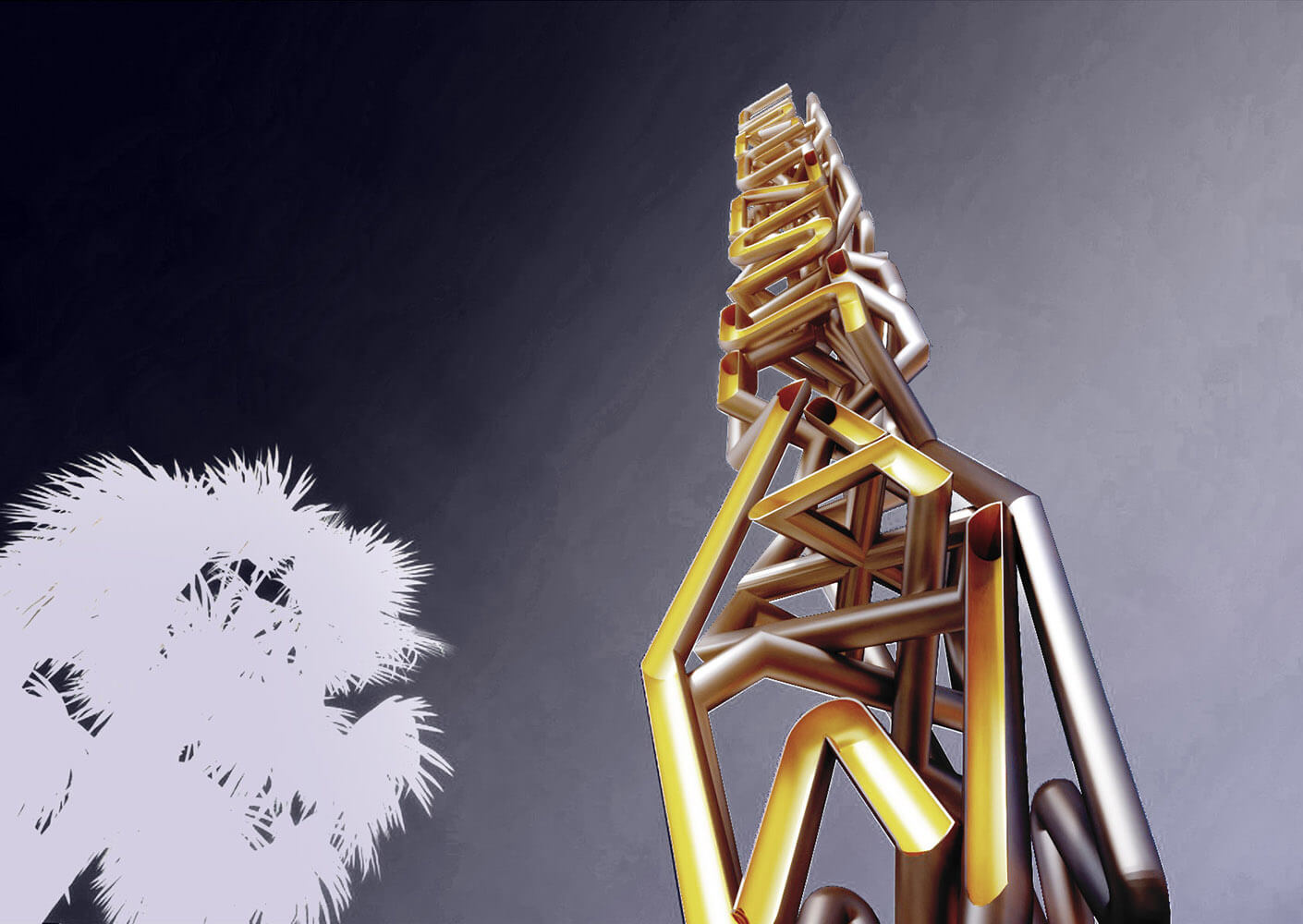

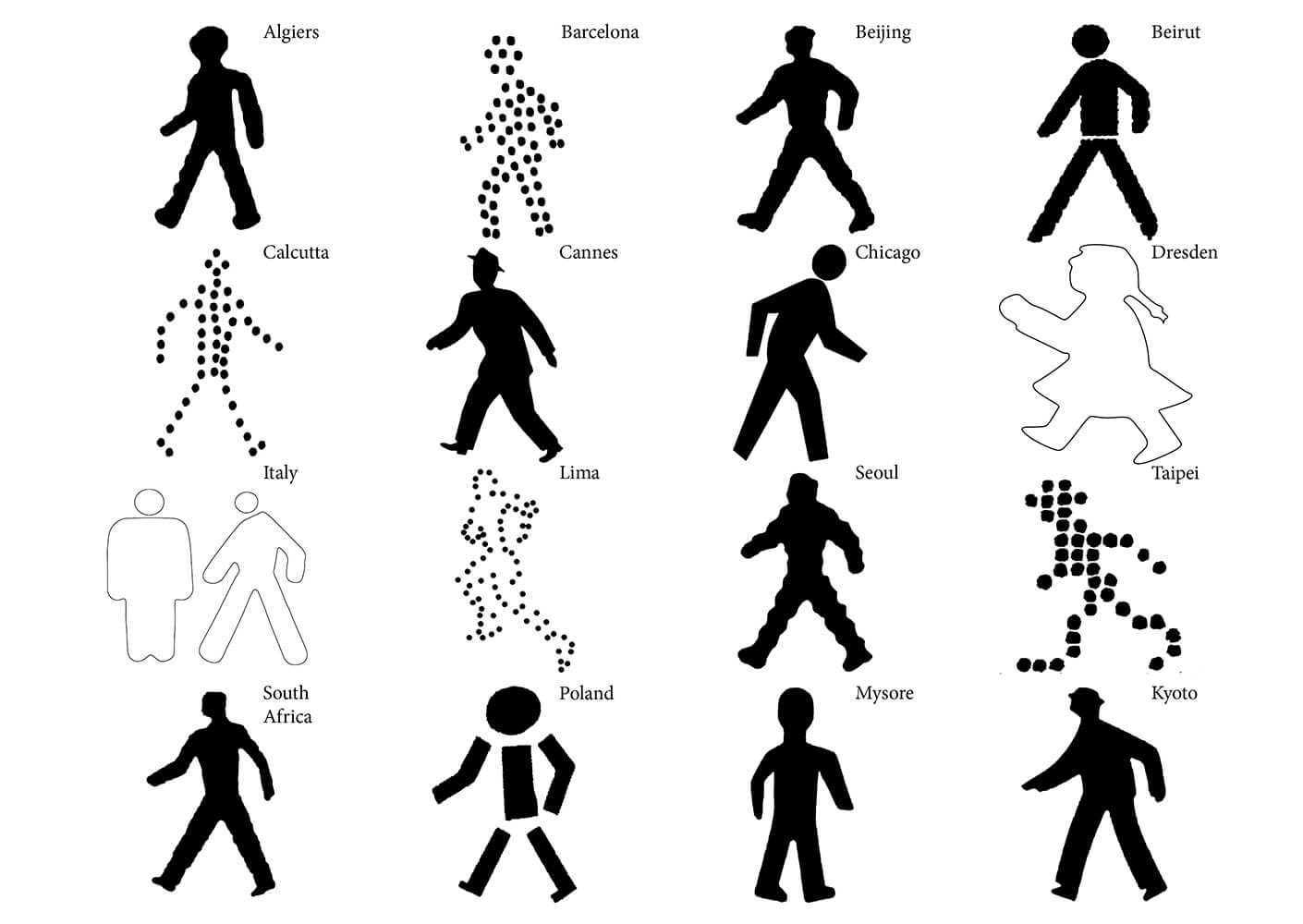

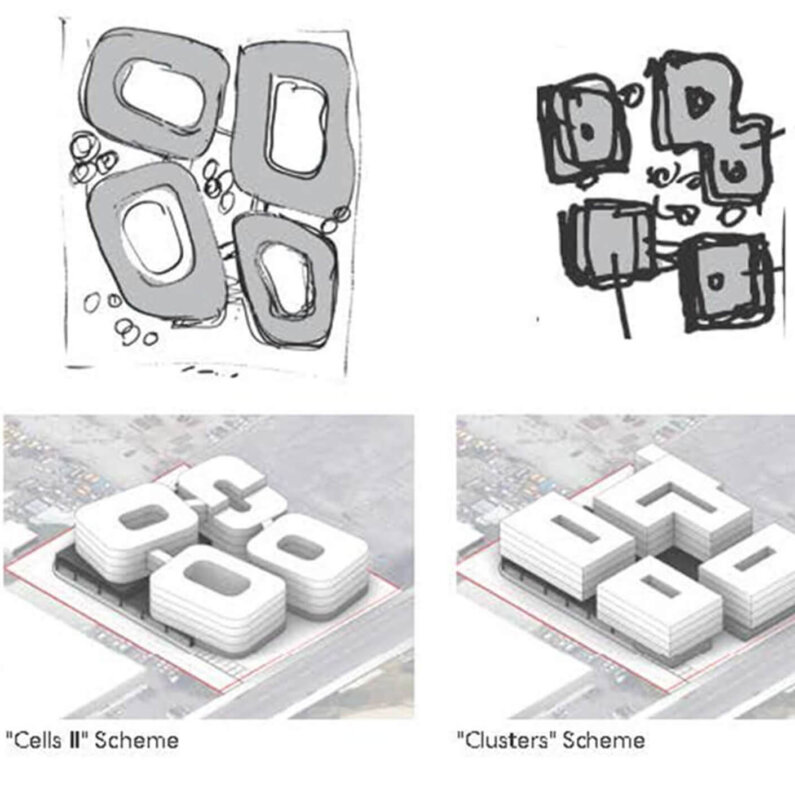

A seminal project that helped Krymsky define his approach to design and narrative came mid-career, when he was chosen to be part of a team competing to design a new museum celebrating the Armenian community in LA. Armenian heritage and identity are far from unilateral. From broad differences in regional dialects to variations in traditional cuisines, the nuanced complexities of Armenian culture made the task of representing it under one roof feel Herculean. Moreover, back at USC, Krymsky studied with a generation of architects heavily involved in Postmodernism, a movement seeking an architecture that could express itself through symbols and allusions to history.

A few decades on, however, postmodernist thought has been reduced to a superficial association with colorful geometric forms, and cartoonish figural representation. This museum for Armenian heritage seemed to be an opportunity for the young designer to apply some of the theory to a more primitive architectural language: “investigating that intersection to find forms that would be both abstract and still identifiable to this really diverse group of people” he says.

Throwing himself into the work, he brought his authentic immigrant background, as well as an academic understanding of historical narrative, to the work. Committed to the cultural research it called for, combined academic research with conversations with as many of his Armenian friends and contacts as would speak to his team. This holistic context became the foundation of the museum’s eventual (winning) design.

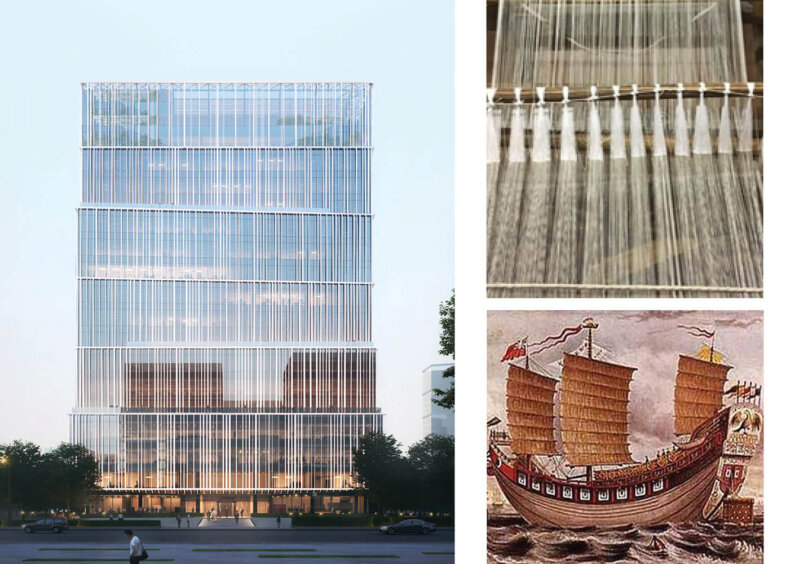

“Humanizing” his work is an ongoing process of discovery for the design director. Expressed through foundational aesthetic decisions like Krymsky’s bold use of color, he’s found a unique way to explore culture in the contemporary landscape. “I always try to take a position on color in my work. It’s an anti-beige mindset,” he says. His bold palette choices—often inspired by raw materials—are refreshing in more ways than one. In addition to offering visual variety, color is closely tied to the expression of cultural traditions. Krymsky understands that it can help weave a story into a single project and enrich an entire city.

Color plays a big role in a project he recently worked on for Clifford Beers housing, one of LA’s most notable permanent supportive and affordable housing advocates, called Corazon del Valle. A permanent supportive and family housing project challenging the existing standard—often poorly landscaped, boxy, neutral-colored structures—Corazon del Valle instead uses undulating forms, lush landscaping, and vibrant colors in the tradition of Mexican Architect Luis Barragán. The color serves as an emotional link to the terra cotta tones of the southwest. Bright pops of pink are an attempt to manipulate perceptions of depth and spatial relationships. “We wanted to create an environment that was the antithesis of the typical multi-family courtyard,” he says. “We wanted to make a place that was intimate, shaded, breezy, and full of plants, and connected to the cultural histories that make up LA.”

Krymsky’s love, understanding, and hope for LA and its residents is palpable in all he designs. An immigrant himself, he brings a strong sense of the need for belonging and tradition to the studio every day. Working on the ground to infuse J.E.D.I. principles into his projects and demanding greater social responsibility in the design world, he is continuously learning and challenging the status quo.

No project becomes a place without stories, humanity, and culture. Through design, Krymsky feels the pulse of the dynamic social landscape of his city, creating places that help to tell, as well as hold, the stories of those who need them most.