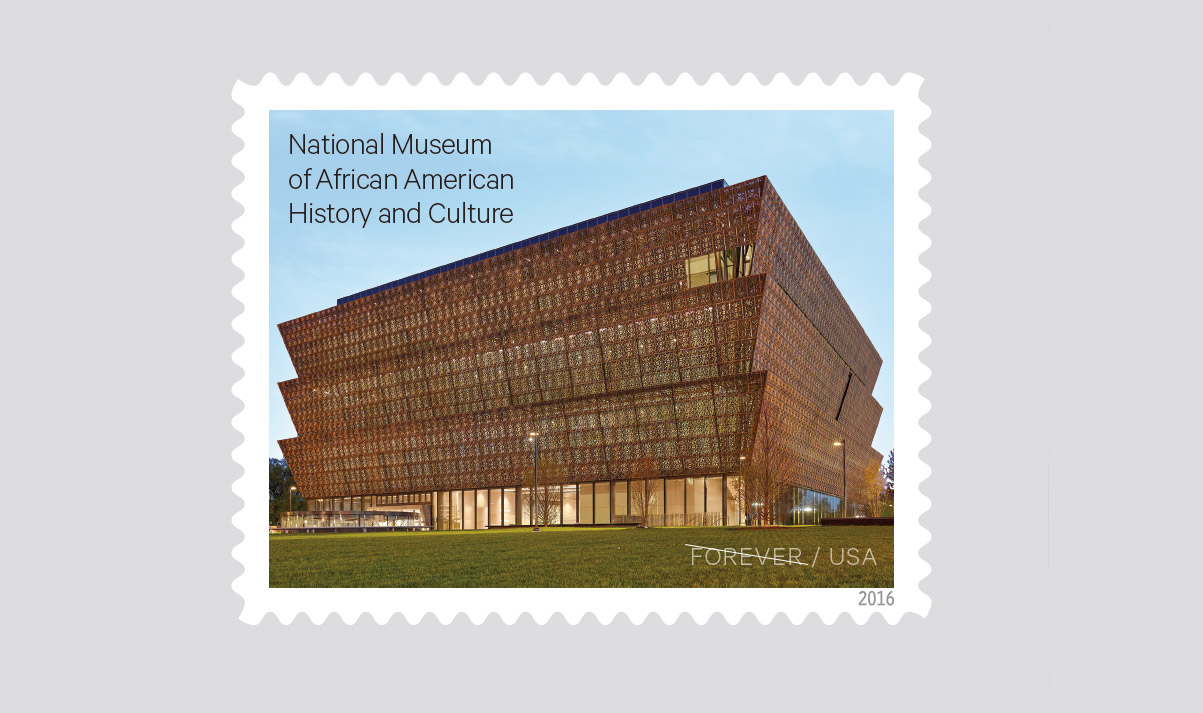

Celebrating NMAAHC’s Five-Year Anniversary

A Perkins&Will Photo Essay

Five years ago, we celebrated the grand opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). As part of the Smithsonian located in Washington, D.C.’s National Mall, this nearly 400,000-square-foot institution honors African American history and culture in a country that has historically overlooked its significant contributions.

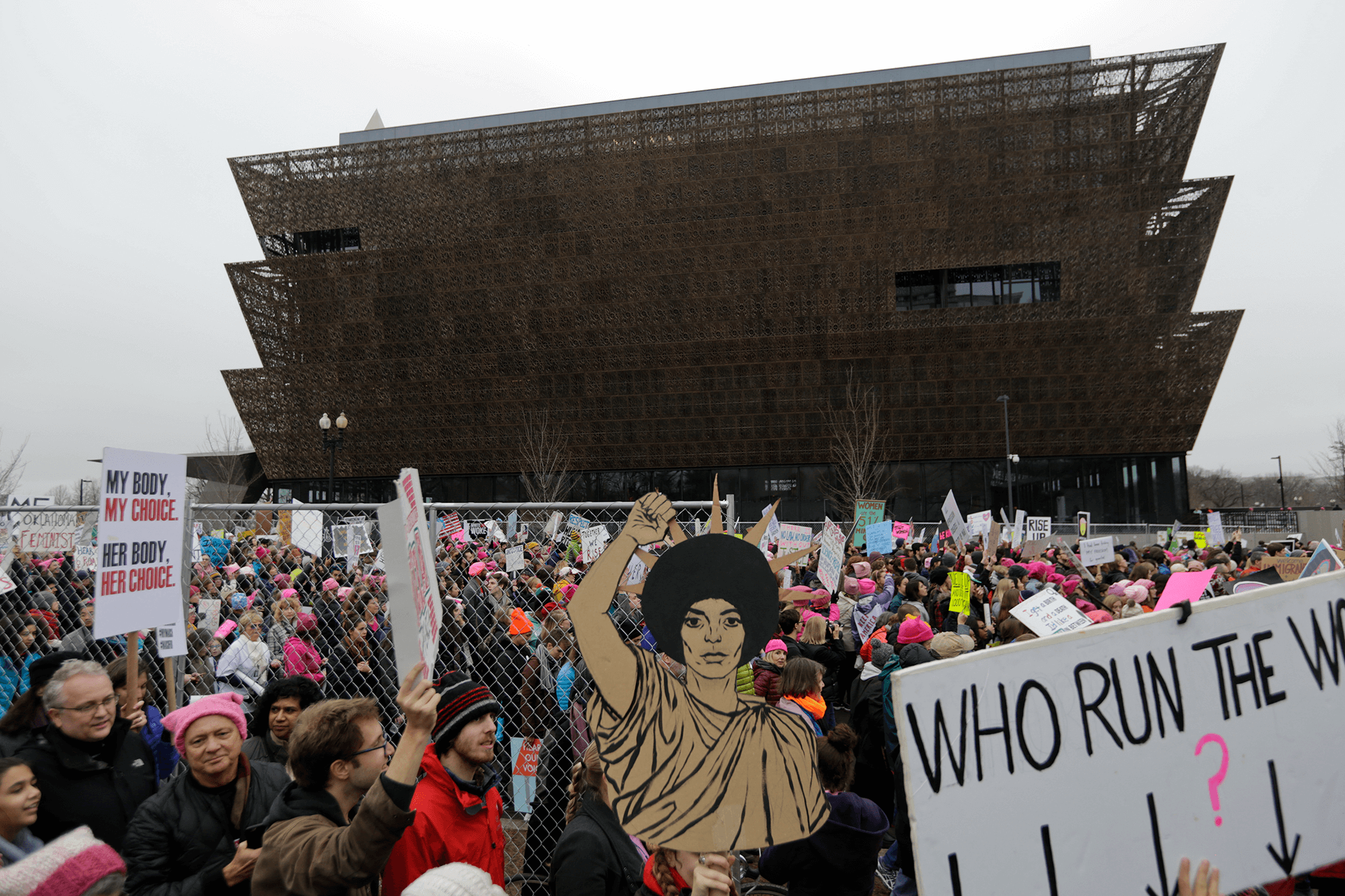

Designed by the collaboration known as Freelon Adjaye Bond / SmithGroup, the building rethinks the role of civic institutions offering forward-thinking modes of visitor experience and engagement. While its intended use was to be a museum, memorial, and space for cross-cultural collaboration and learning, it was later activated as a place for peaceful protests and demonstrations in 2017 and 2020 in the wake of racist violence.

This break from programming proves its architectural staying power, underpinning why now, more than ever, we need cultural institutions to represent historically marginalized communities’ experiences and to act as a driver for positive social change.

The Smithsonian named Lonnie G. Bunch III the founding director of the NMAAHC.

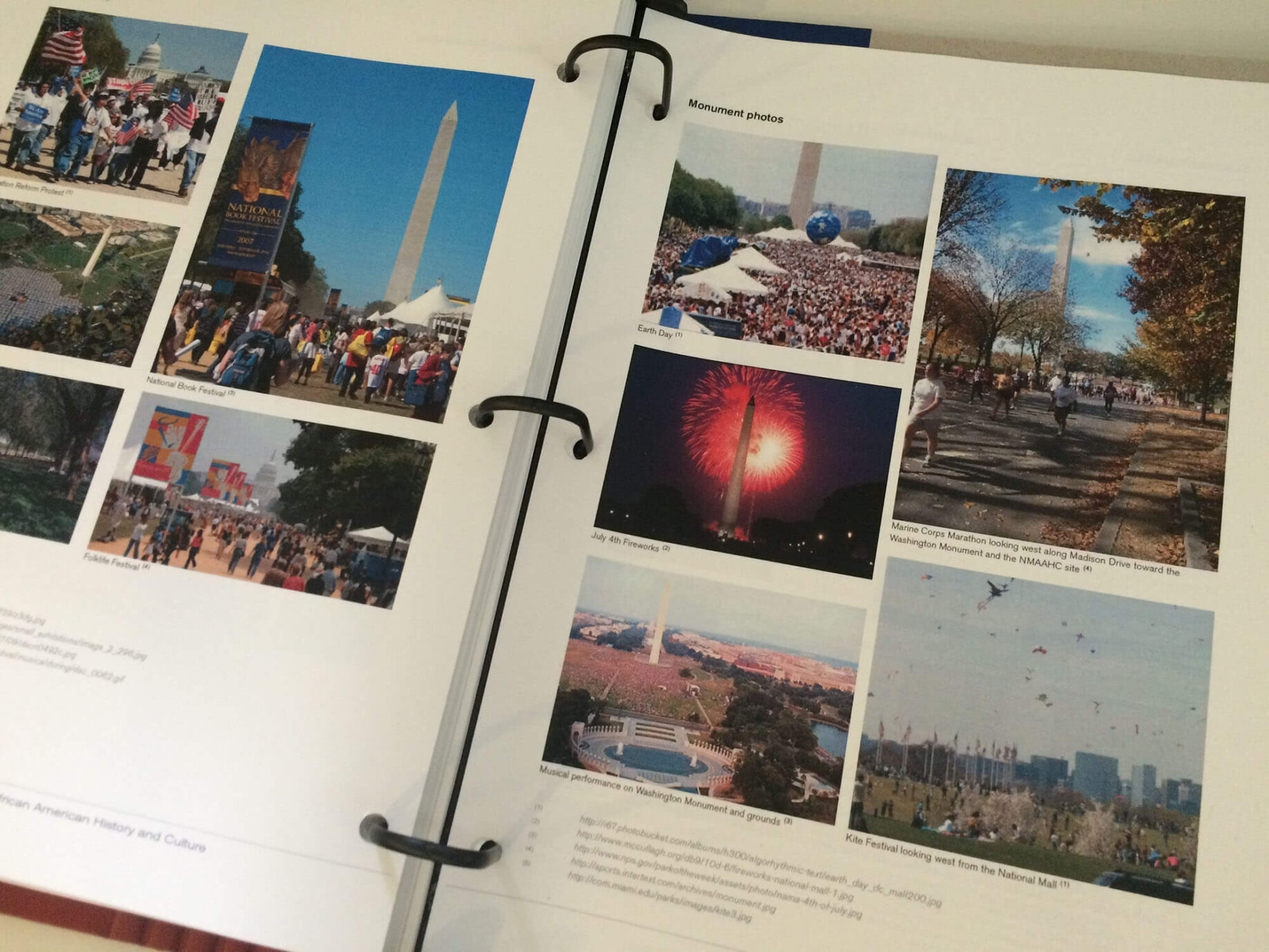

The Smithsonian announced the NMAAHC will be built on the National Mall between the Museum of American History and the Washington Monument.

The Smithsonian selected Phil Freelon and Max Bond, both prominent African American architects, to carry out the museum’s first phase of planning and pre-design work.

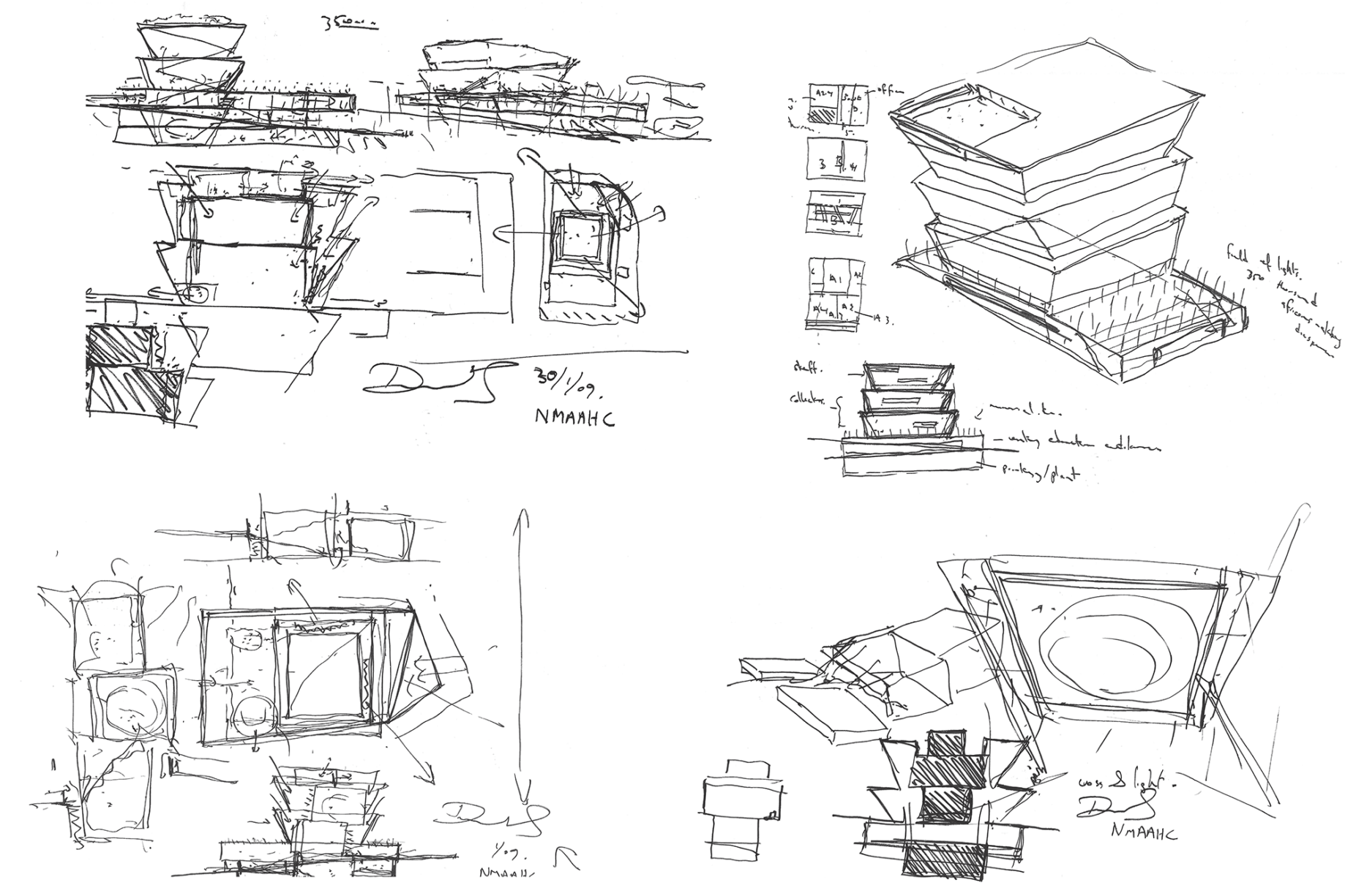

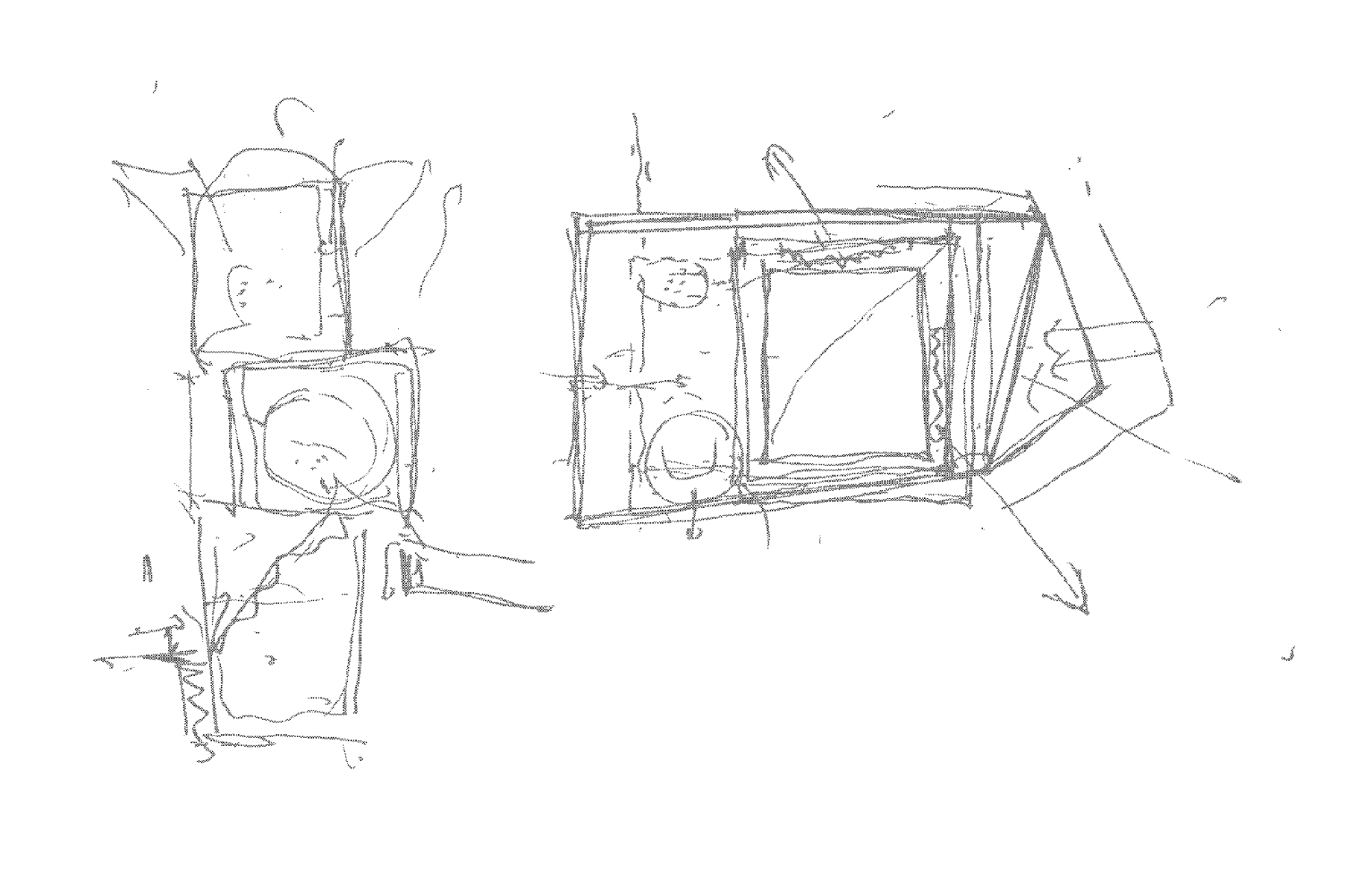

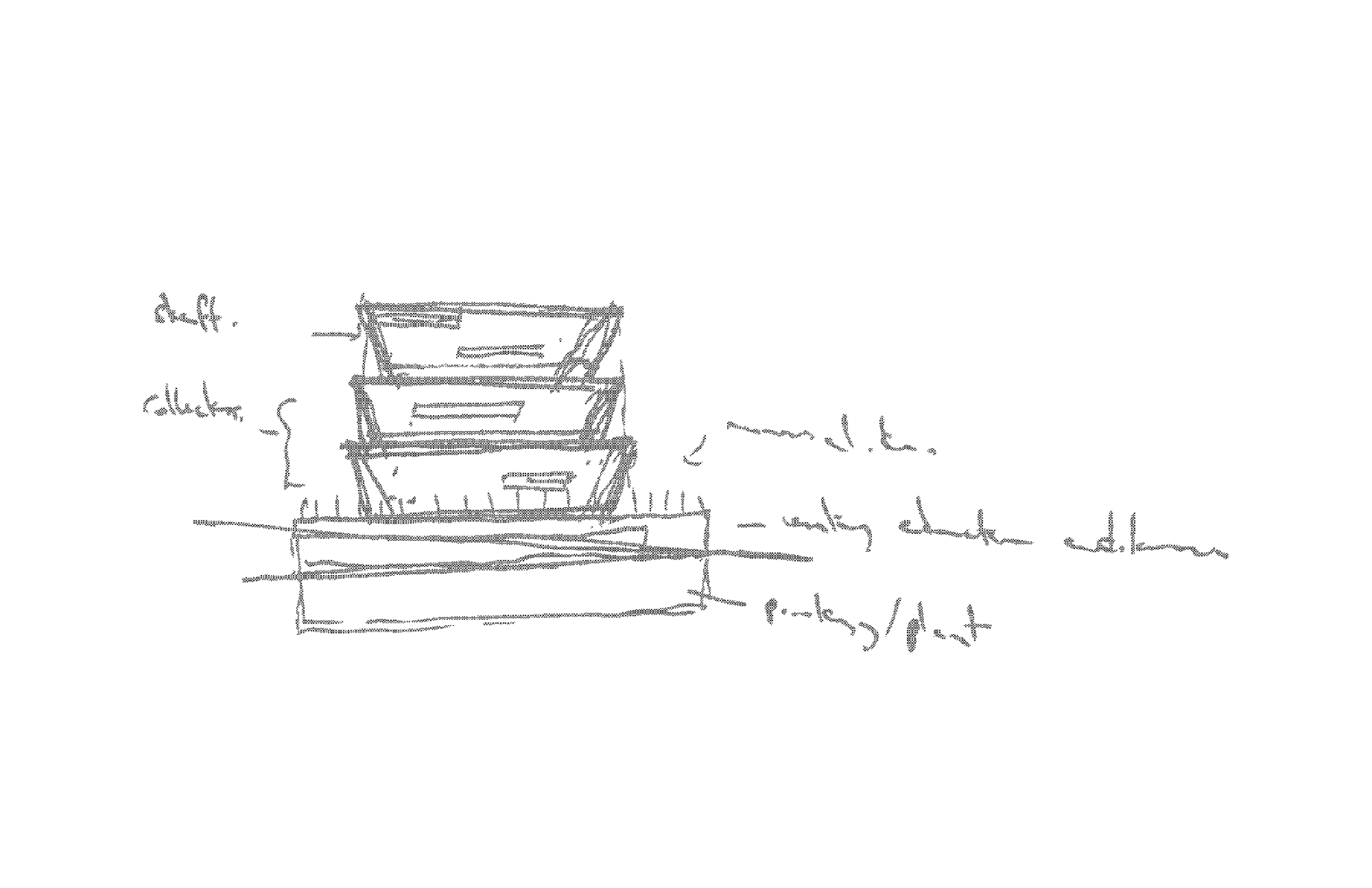

Phil Freelon and Max Bond completed the six–volume Phase 1 Master Program and Planning document, which served as the basis of the design of the museum. This document provided recommendations for the design of the museum based on visitation and audience research, public engagement, collections storage plan, site analysis, facility and exhibition master plan, accessibility, engineering systems, sustainable design, and other museum requirements.

The museum began soliciting design proposals through an internal design competition. Lonnie G. Bunch III, the museum’s founding director, led the competition selection committee. The nine-member group included notable design community members, such as Linda Johnson Rice, co-chair of the Museum Council and Chairman of Johnson Publishing Company Inc.; Robert Kogod, member of Smithsonian Board of Regents and president of Charles E. Smith Management LLC; and Robert Campbell, an architecture critic at The Boston Globe.

The committee of judges for the NMAAHC design competition selected Freelon Adjaye Bond/SmithGroup to carry out their vision for a museum dedicated exclusively to showcasing African American life, art, history, and culture.

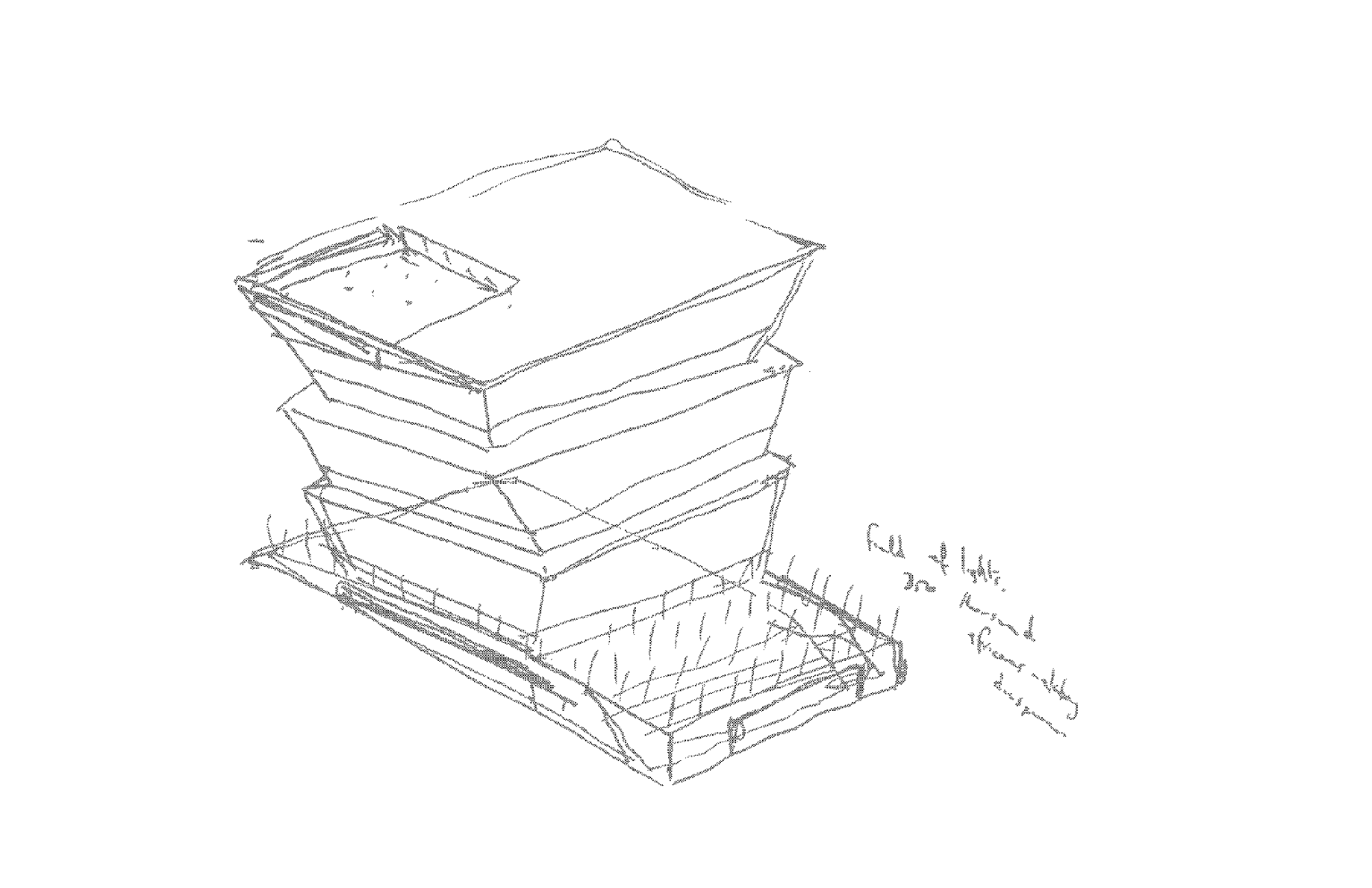

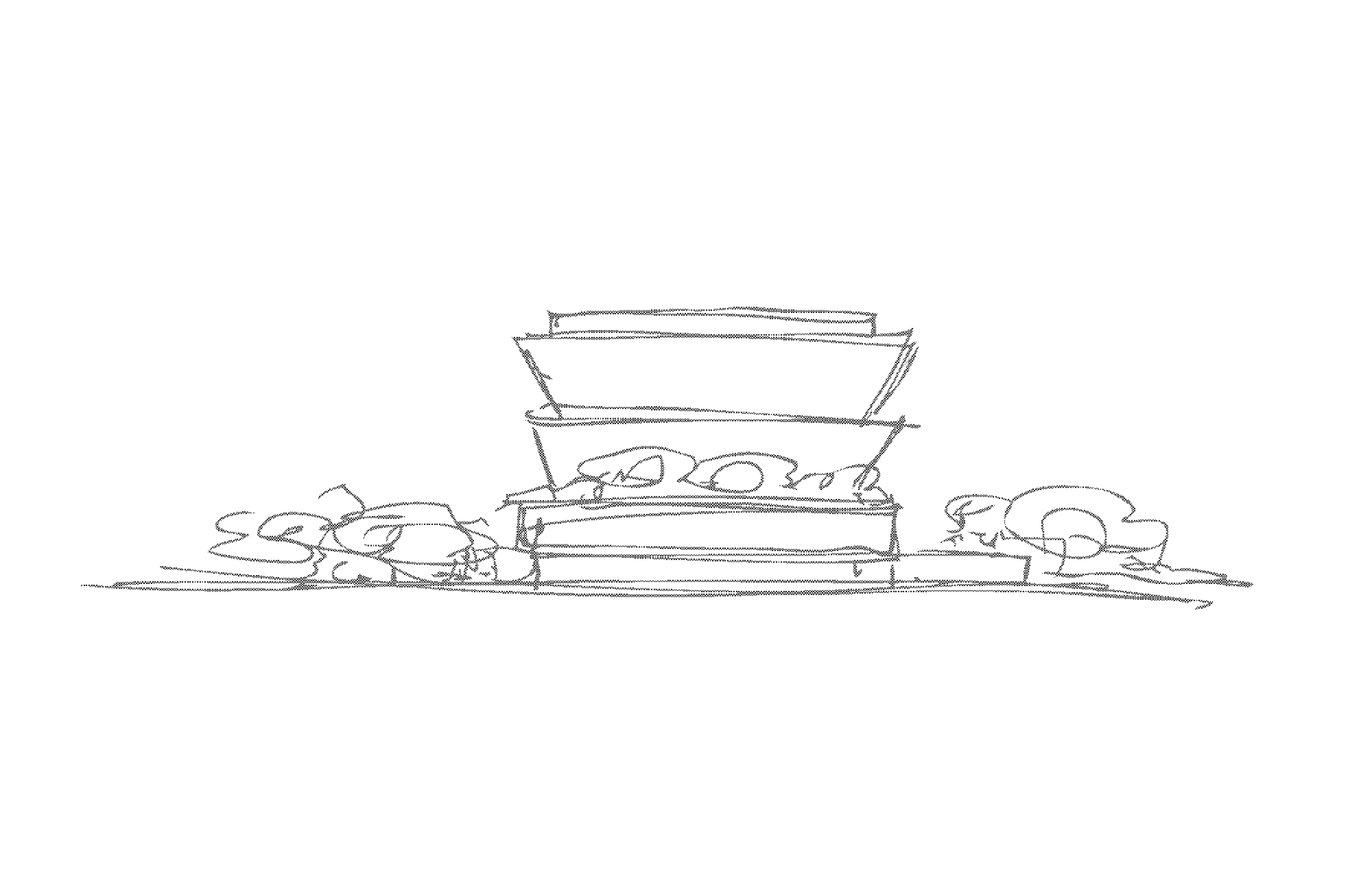

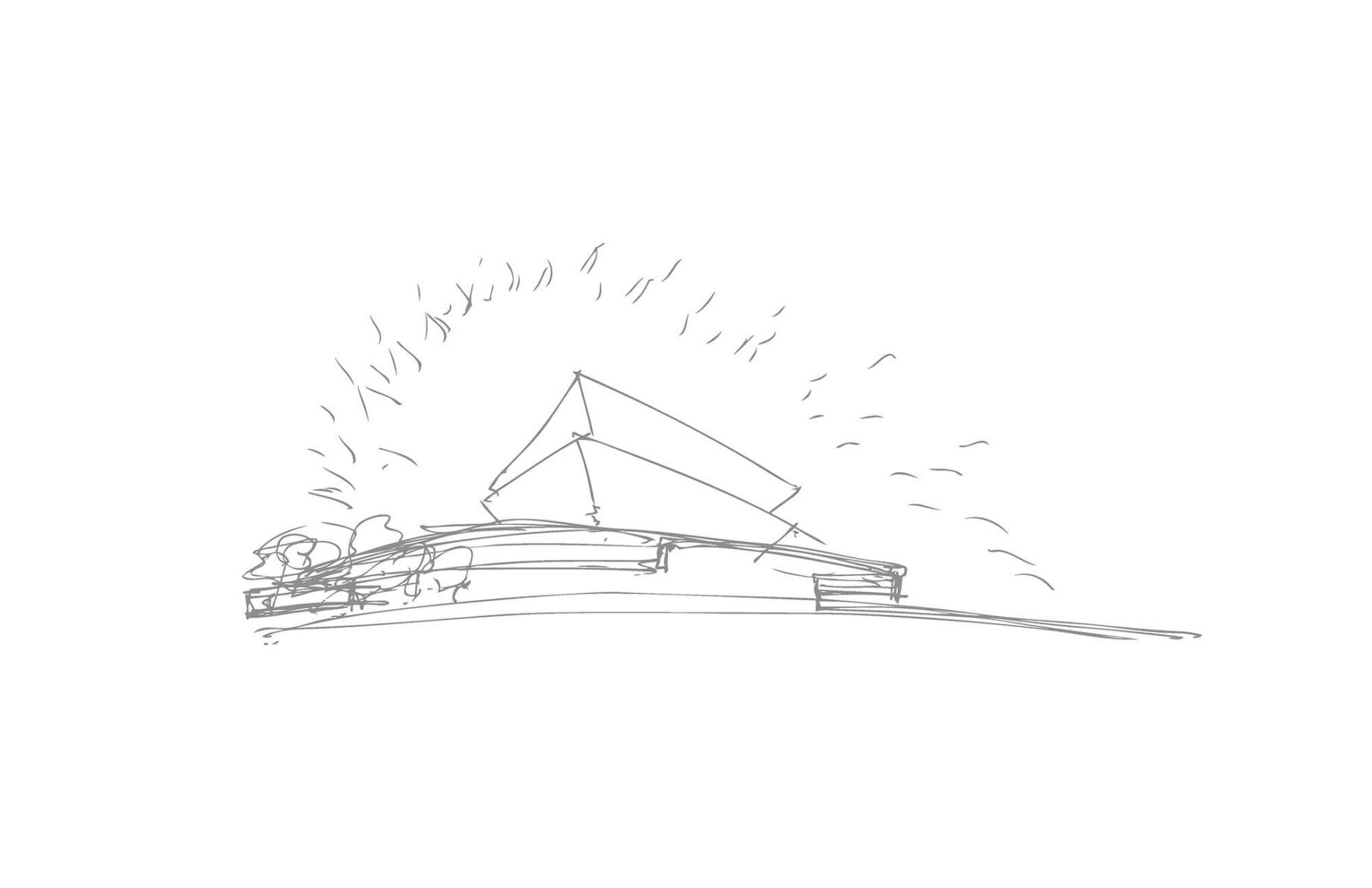

The multidisciplinary team gets to work, and designs come to life with the NMAAHC leaders’ input. Principals Phil Freelon and Zena Howard are tapped to lead a team with over 30 consultants, honing in on their cultural expertise and perspectives as Black architects.

The museum selected Ralph Appelbaum Associates as the exhibit designer.

Construction started on the museum’s grounds, becoming the largest and most complex project in the country, in large part because of the challenges of building 60% of the structure below ground.

The Smithsonian broke ground for its 19th museum and celebrated with a private opening ceremony. Former president Barack Obama spoke to the significance of creating this new building within the five-acre site.

The museum’s base took form while making way for significant artifacts that determined the below-ground makeup.

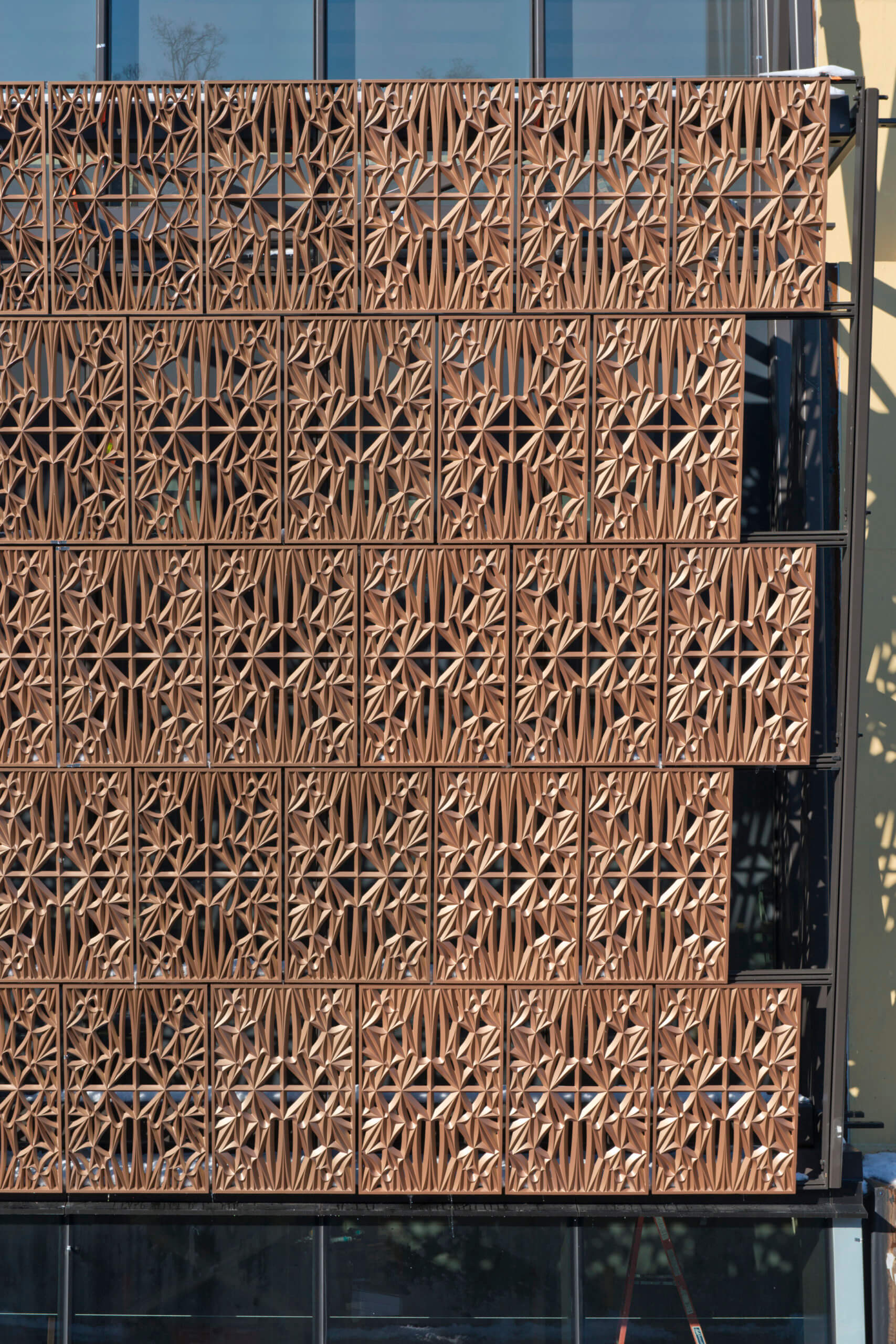

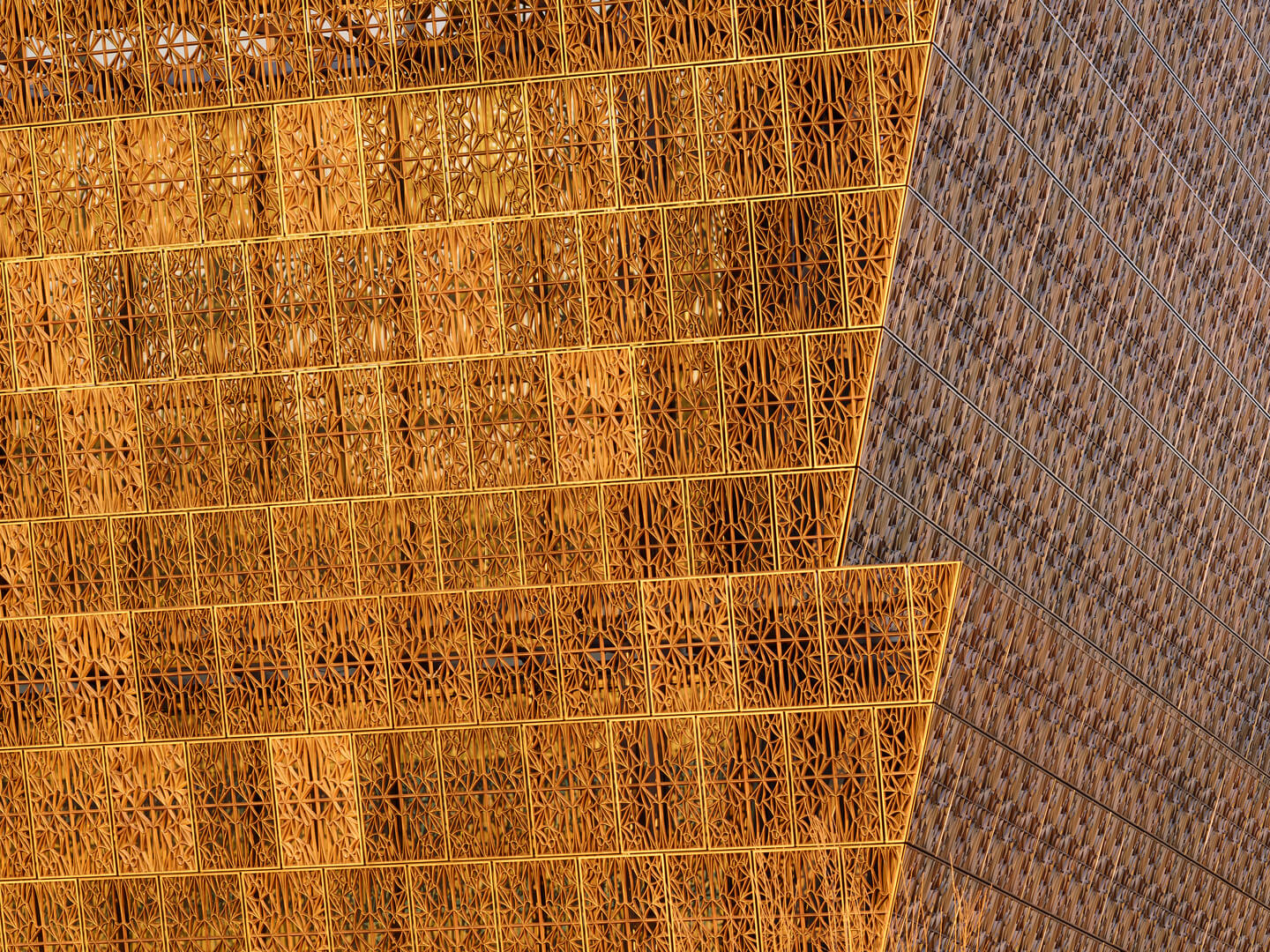

The Commission of Fine Arts and the National Planning Commission approved treatments and materials for the panels installed for the corona.

The team completed the above-grade steel-and-concrete superstructure of the roof level; glass installation began on the fifth floor.

On the morning of September 24, the NMAAHC held an inaugural ceremony outside. Later that afternoon, the institution officially opened as a public museum.

The emotional and celebratory inauguration included a speech from former president Barack Obama in front of 7,000 official guests. An opening ceremony followed, with words from notable figures such as Oprah Winfrey and former president George W. Bush, who signed the 2003 bill that authorized the museum. Singers Stevie Wonder and Ms. Patti LaBelle also performed.

The late Representative John Lewis, a veteran of the 1960s civil rights movement, spoke at the opening ceremony and said, “This place is more than a building. It is a dream come true.”

The museum welcomed 1 million visitors in a span of four months.

To celebrate its third year of operation, the museum held two events depicting how African Americans have influenced life through creative mediums such as architecture, film, food, community planning, and urban design.

From September 27 to 29, the museum held “Shifting the Landscape: Black Architects and Planners, 1968 to Now,” a discussion that investigated Black architects’ and planners’ activism, engagement, and their impact from the previous 50 years.

A little under a month later, from October 24 to 27, they celebrated the first Smithsonian African American Film Festival, which displayed both historic films and contemporary works.

The Freelon Group—part of Perkins&Will since 2014—won an American Institute of Architects’ Honor Award for Architecture, the AIA’s highest award, for designing one of the most notable projects in the past decade.

As a public health precaution to COVID-19, NMAAHC temporarily closed to the public starting March 14, 2020.

The NMAAHC formed a coalition to document, collect, and record artifacts from the Black Lives Matter movement left behind at Lafayette Square, located in front of The White House.

After reopening on May 14, 2021, the museum kicked off the month of June by observing both Juneteeth, the country’s second Independence Day, and remembering the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre with virtual programming and educational resources.

Since opening, the museum welcomed more than 7.5 million visitors in person. To commemorate its success, the institution will celebrate with a series of new exhibitions under the theme “Living History,” exploring cultural and social aspects of the Black diaspora. This includes the Smithsonian Anthology of Hip-Hop and Rap CD and book, an art exhibition depicting the Black Lives Matter movement and violence against African Americans, and an art exhibit with pieces that portray resilience in Black communities.

“The National Museum of African American History and Culture is a celebration of how architecture can help create a more just, equitable, and inclusive world. Five years ago, our firm heralded the new Smithsonian museum because it prioritizes the cultural heritage and identity of African Americans—which are historically overlooked in our country.

But the vision to create and rethink the role of a civic institution and how it honors previous generations has been building up much longer. We are proud of the work we’ve accomplished with our NMAAHC partners: The museum is an icon and an inspiration to future generations—a testament to the power of design and placemaking to create positive social change.”

– Gabrielle Bullock, Principal, Director of Global Diversity