Breaking Barriers to Entry, Linzi Cassels Designs for a More Equitable Future

At the intersection of science and art, architecture draws individuals who have both technical aptitude and untethered creativity. Linzi Cassels always saw herself at that intersection, yet never stopped pushing the limits of her creative side. Both an architect and artist by training, the Scottish-born Interior Design Director chose to chart her own course through the design profession through an education in the arts. Now, she’s at the helm of an award-winning architecture and interiors studio in London, uplifting the voices of other women in the industry, too.

“Growing up in social housing, I didn’t expect to have the same opportunities as others who chose to pursue art. From the moment I decided to attend the Glasgow School of Art, I understood what it meant to be an outsider.”

Cassel’s mother was a drama teacher who moved the family into social housing after a divorce left her with few resources, but a commitment to educating her children in the arts. One of Cassel’s earliest memories is a day trip with her to see a Salvador Dali painting. “[My mother] understood that there’s nothing like seeing art face-to-face, and having that visceral experience of seeing. I’ve carried that with me my whole life.”

While much of her family was involved in the fine arts, Cassels was attracted to a more professional career—one that could offer stability and reliability if the capriciousness of life got in the way.

“Early on, I’d shown a penchant for more academic work, and I was interested in combining my creative and intellectual passions rather than pursuing one or the other. Architecture seemed to be the natural fit. But looking back, I had no idea what architecture was.”

At the time Cassels was in school, girls took courses like home economics, and boys had exposure to more engaging courses like woodworking and principles of engineering. She saw this disparity reflected in her incoming university class, where women were often behind in the basics—from drafting techniques to model making—than men. “I looked around the studio, at all the drawings hung on the walls and the models on the tables. And I thought to myself, ‘I don’t even know how to begin to create a drawing.’ It was incredibly daunting, and though I’d been artistic my entire life, I felt wholly unprepared.” Little by little, though, she got her bearings.

Cassels’ time at architecture school culminated in a thesis project on crematorium design. “I know, it might appear to some to be an odd choice, but my crematorium was a space richly situated in its landscape. It’s also a deeply symbolic form, and I nestled it in this rural, forested setting. I was interested in humanizing a space that no one really thinks about entering until some humanity is gone. That was the challenge.”

After graduation, Cassels found herself in London in the ‘90s at the peak of trend toward designing speculative, and often uninspired, office spaces. “I became disenchanted, to say the least,” she says, recalling that the work was often anonymous, and a far cry from her heavily experiential work in university. “My family would make fun of me, asking me what sorts of toilets I’d designed that day.” Still under 30 at that time, she knew she had the flexibility to rework her career. She decided to return to school and pursue the degree in fine art that always lingered in the back of her mind.

The ‘90s were also explosive years for the British contemporary art scene, as artists like Damien Hirst captured the public imagination and expanded the idea of what fine art could be. Cassels started at the renowned art school, Central St. Martins, part-time, keeping a job in an architectural office during the day and taking courses or working in her studio at night. But what she conceived of as her day-job turned out to be the source of much of her inspiration throughout her art studies. “It was an amazing feeling to go to work not in solitude, but surrounded by teams engaged in collaboration.”

All of the interior designer’s work is a product of invaluable and integral collaborations between her team members, collectively working towards a beautiful solution.

One pivotal project for Cassels was a design for a large pharmaceutical company interested in an immersive brand experience that went above and beyond the ‘one-size-fits-all’ layouts of her previous experience. In 1989, the client’s vision was quite forward-looking for the time. “In a way, [the client] foreshadowed the trends in workplace that we’re seeing now, in 2020. These are the trends I was hungry to design and deliver, that put people first.”

An early adopter of the concept of the playful, interdisciplinary office design that’s been embraced and in-demand for several years now, Cassels finds inspiration in the creation of new spatial types, combining only the best and most expressive elements in her designs and forgetting the rest. “I was always focusing my lens on interior landscapes and the storytelling ability they held. I was still very much entrenched in the built environment, and in design. It was a hard realization, but an easy choice, to return to the design sphere after that, and as an interior designer.”

Specializing in corporate interiors, Cassels uses her sense of interior landscape to tell the story of a company, weaving unique narratives through her spaces and furnishings. She and her team often arrive at their solutions and predictions through hands-on modeling and prototyping, engaging with unbuilt concepts and competitions to sharpen their thinking.

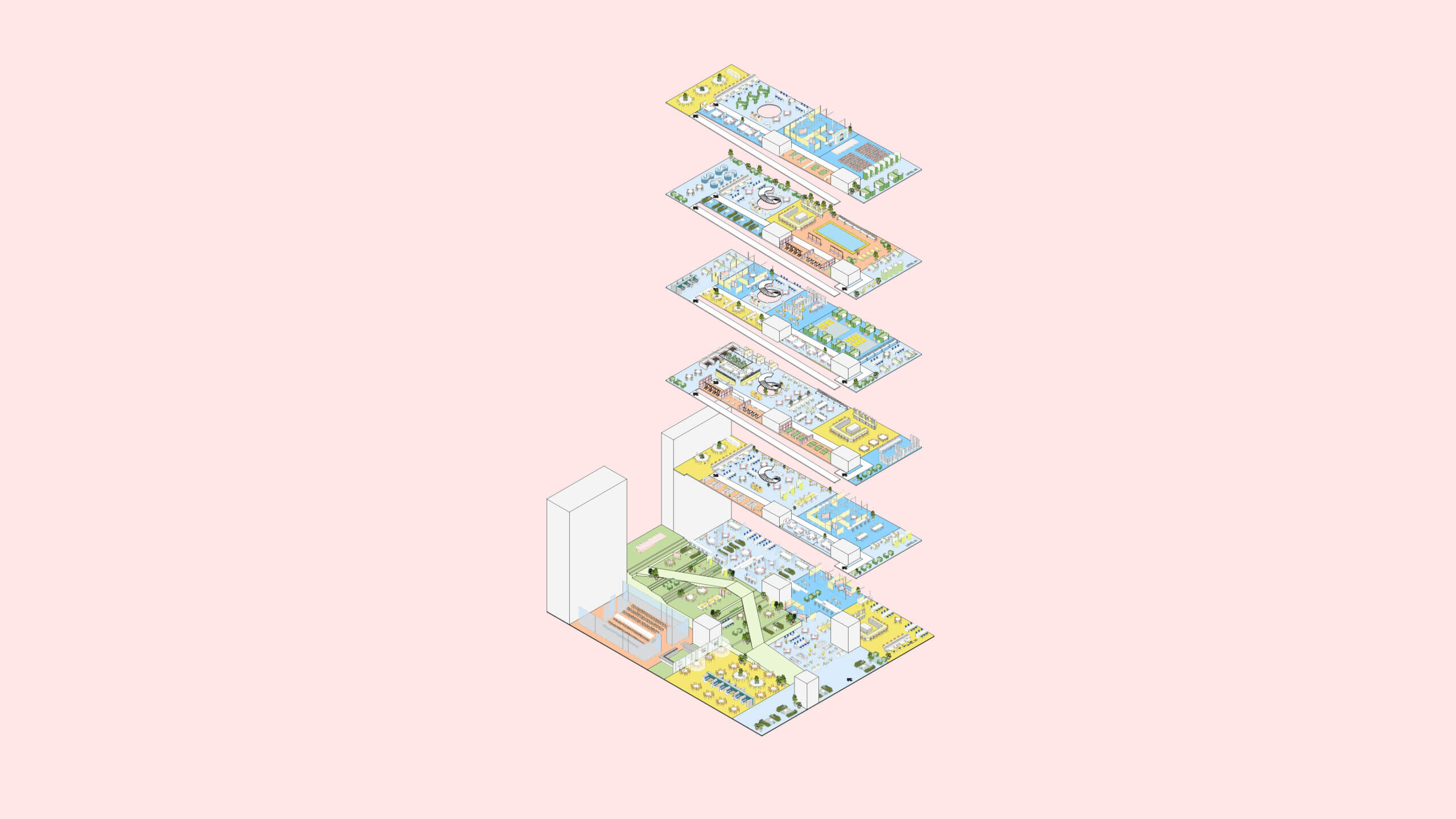

A recent example is a new building type Cassels conjured with her studio: Think of a hotel, but one where only 20 percent of the building is dedicated to guest rooms, and 80 percent is slated for dynamic public spaces. She’s flipped the hotel blueprint on its head. “The studio is full of designers looking to push the envelope and think creatively about what’s to come next. This may have been an unbuilt plan, but we pitched it to competitions and talked about it on our studio-wide podcast, Future Dialogues. It’s a part of the new building type revolution that has already begun to make an impact.”

Cassels has introduced many other projects and cutting-edge innovations to team members and clients through the Future Dialogues platform, including some thought leadership that became very relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Dialogues are delivered like a podcast for the whole studio to tune into. Staff get a glimpse of what’s cooking in all corners of the studio, or hear the ideas of emerging designers. Recently, Cassels hosted one Dialogue inspired by her observations of the workplace emerging from lockdown. Living in London, she and her husband observed how much worse the traffic had been since the onset of the pandemic, with residents relying more on personal vehicles and fearing the risks of public transit. This prompted Cassels to confront the issue of commuting once the rest of the city reopened.

“The ‘new normal’ doesn’t have to regress. We currently have this enormous creative potential that we can either seize and use to impart change, or ignore and lose,” she says. “I see the new normal of the workplace being incredibly more decentralized, with an HQ of sorts in the main business district zone supported by several surrounding satellite offices, allowing colleagues to work closer to home with greater convenience and safety, as social distancing measures will surely be increasingly difficult in dense, inner city locations.”

The “15-minute” city, an urban planning strategy in which city dwellers have access to all essential needs within a 15-minute pedestrian radius of their home, acted as a model for Cassels’ conjecture, designing for not only convenience, but environmental responsibility and an active lifestyle for residents of all neighborhoods.

Cassels has already begun to adopt a new attitude toward healthy work-life balance, making it central to her work as an interior designer: “Now more than ever, we are truly designing for life, not just work. Commute, workplace health, personal well-being, and urban planning are all interconnected in our lives as residents of cities as well as designers of them.” Through self-reflection and a renewed mindset that seeks simplicity, she is ready to make the most of this moment of profound change, and mold it to better the lives of all.