A call to action at a colleague’s speaking engagement crystalized Mary Dickinson’s dedication to healthy materials more than a decade ago. Dickinson, now a regional sustainability practice leader in our Dallas studio, recalls healthcare practice leader Robin Guenther passionately theorizing, “Shouldn’t cancer centers be built without materials that contain cancer-causing substances?” At the time, Dickinson was working on the design of a cancer center where her own mother was receiving treatment. Guenther’s words had an indelible impact.

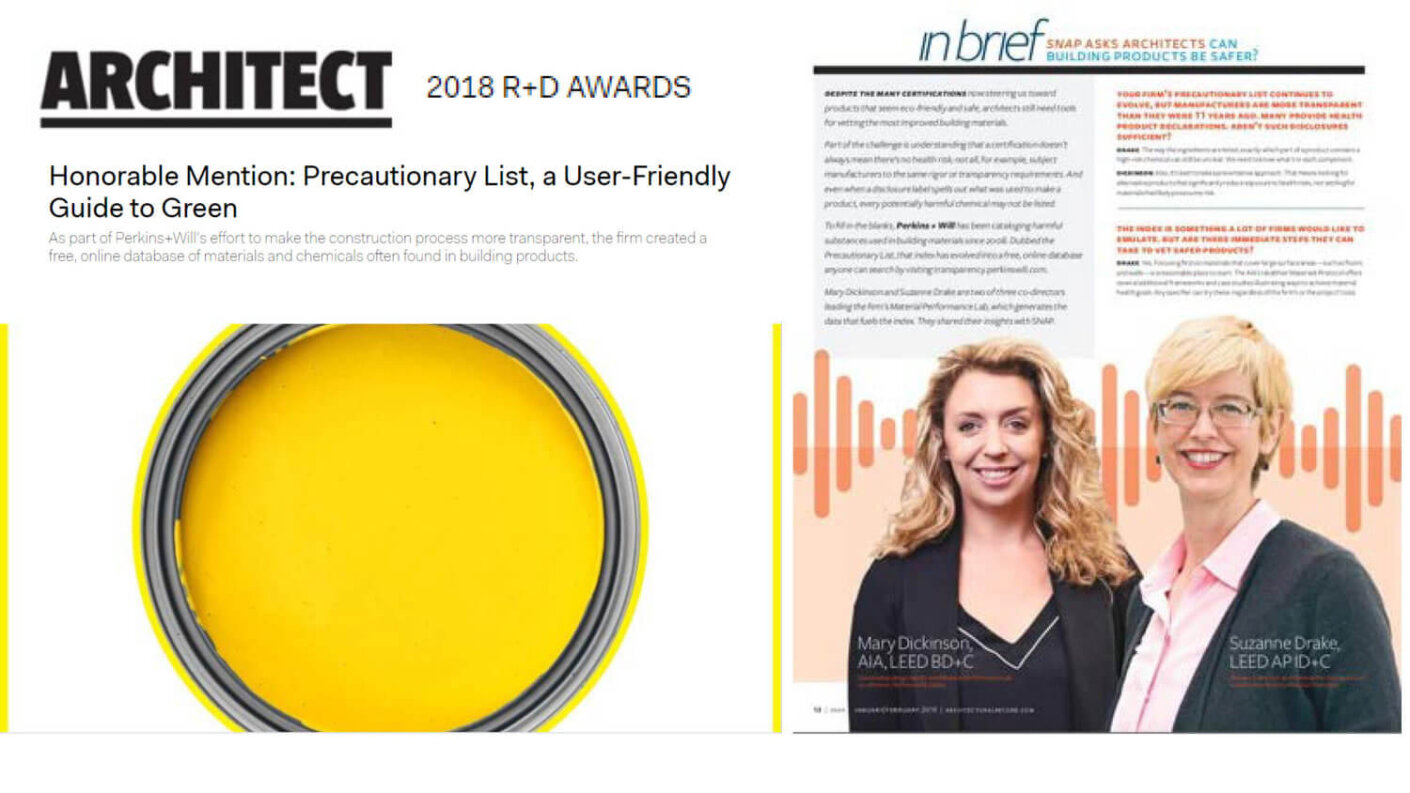

When a pervasive inquiry into the built environment’s impact on human health ignited a movement over a decade ago, we were well positioned to respond with meaningful action. In 2008, we launched the Precautionary List, a compilation of the most ubiquitous problematic substances in the built environment. Three years later, we debuted the Transparency website, a user-friendly digital database of these materials. Dickinson was instrumental in carrying this initial step forward, advocating for the importance of the work and managing future updates to the list as well as the site.