Tucker Dupree has won swimming competitions all over the world. In 2008, he qualified for the U.S. Paralympic Team and competed in Beijing, then in London in 2012 and Rio in 2016. He won four Paralympic medals during his swimming career. The now 33-year-old swimmer, who became 80% blind at age 17 after being diagnosed with Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, recognizes that his story is a relatively unique one. “I was traveling the globe with some of the most capable and athletic people who embodied a variety of neurological and physical differences,” he says. “It was awesome and inspiring, to say the least.”

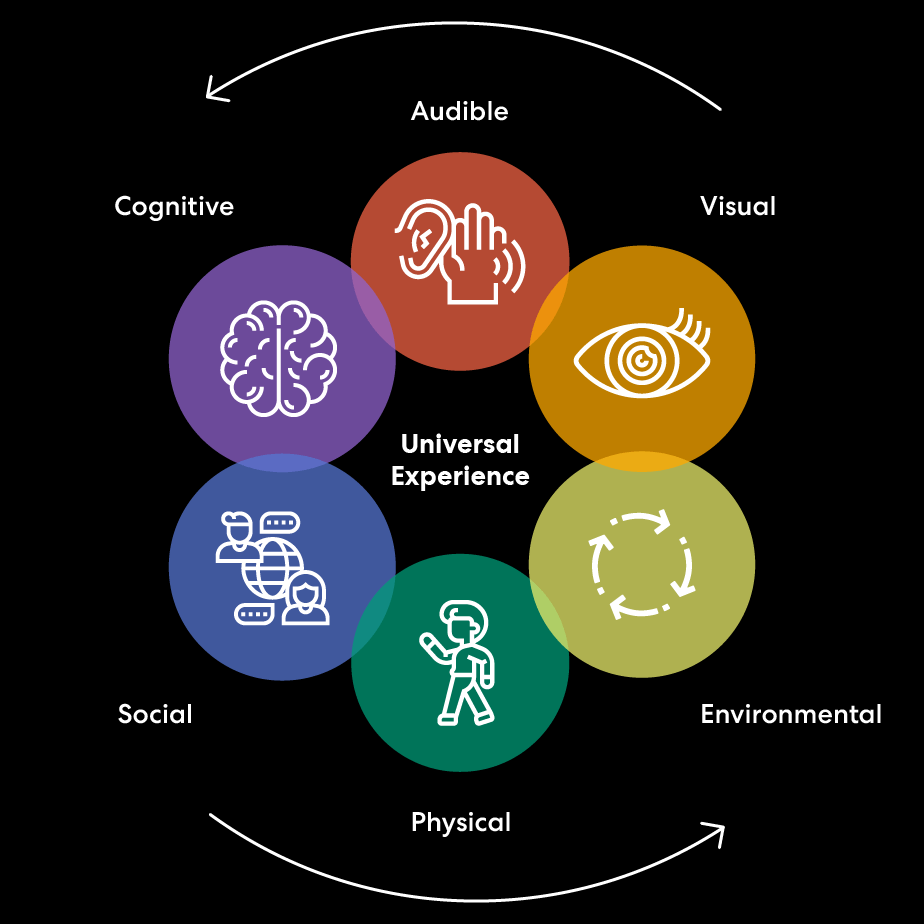

But visiting different countries and experiencing varying accommodations for Paralympians also shed light on the shortcomings that can arise from a lack of universal design standards to support both physical and neurological needs. Dupree cites different elevations of pool decks, which create obstacles for visually impaired people who use a cane, and venues in which the acoustics make it difficult for teams to communicate when the crowd cheers.

It’s fitting, then, that Dupree is now part of BP’s global Workplace Colleague Experience team, responsible for creating engaging and inclusive workplace environments in the Americas region. “At the Paralympics, I saw thoughtfully designed spaces and not so thoughtfully designed spaces,” he explains. “Back then, swimming was my job, so I understand how awful it can be coming into an environment where you have to excel while you also can’t be your true self.”