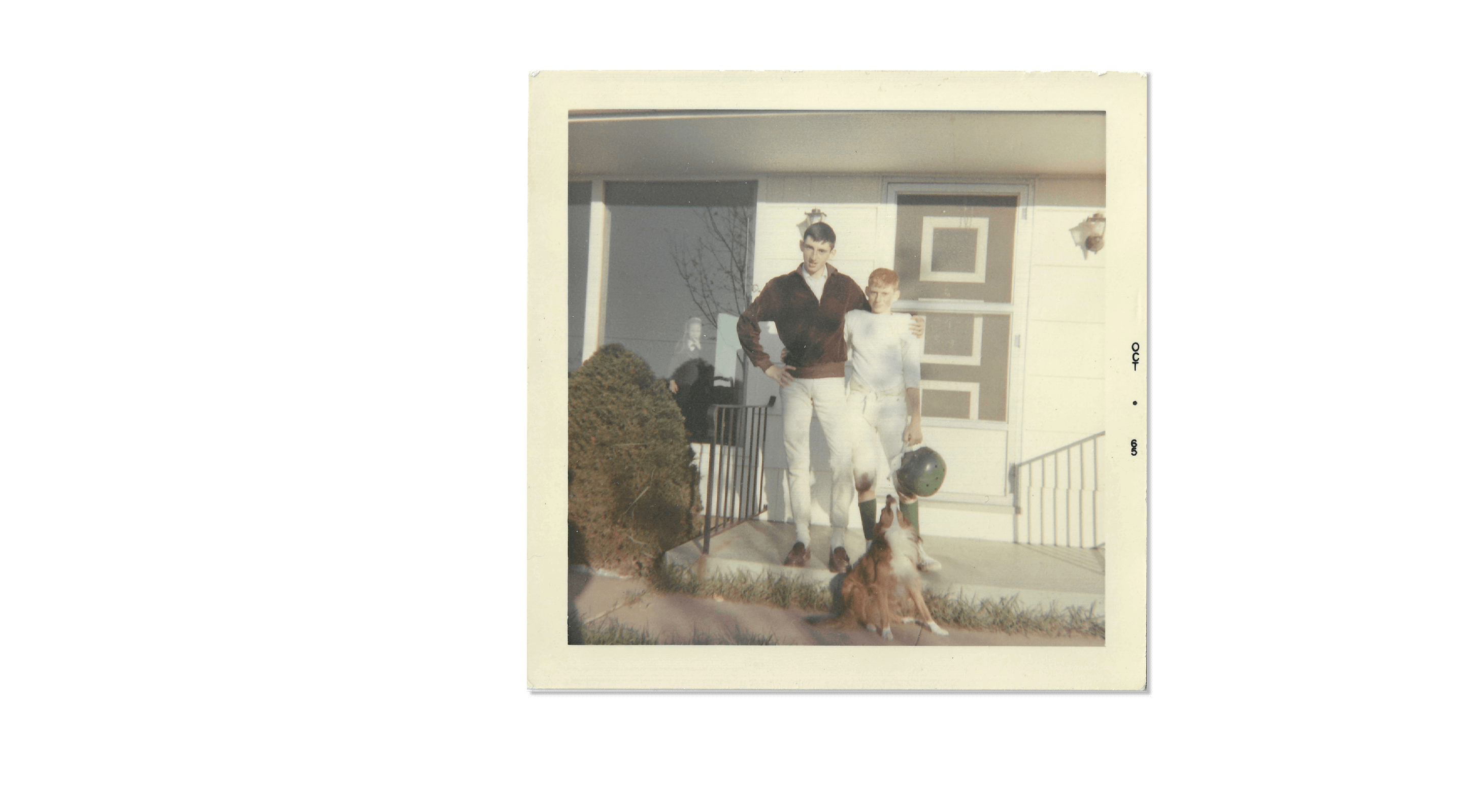

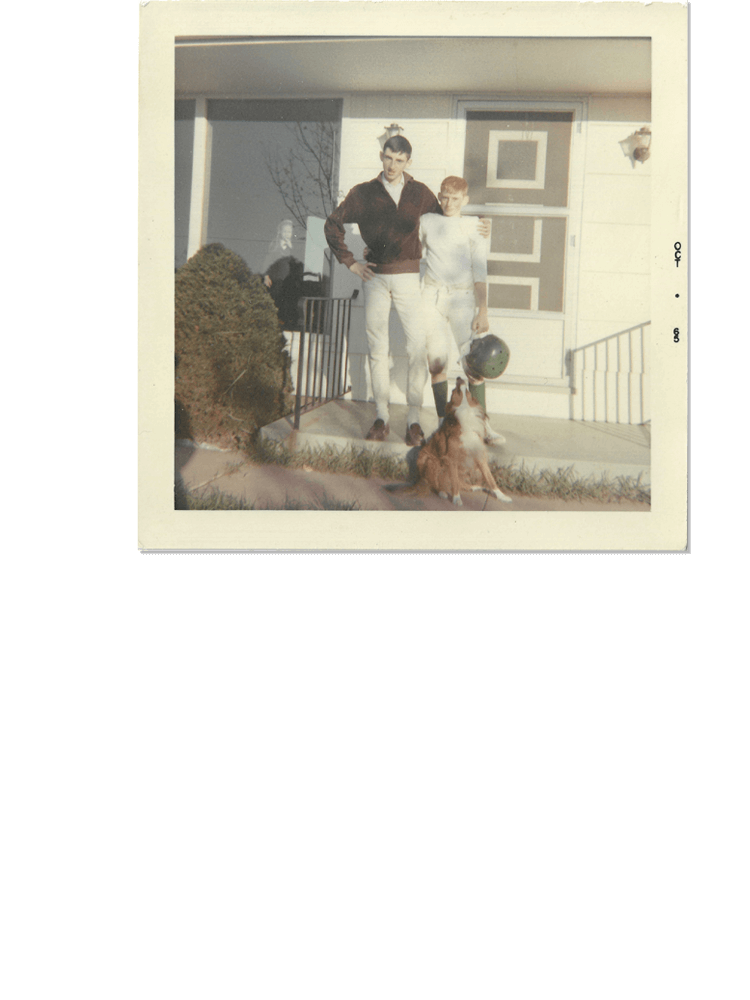

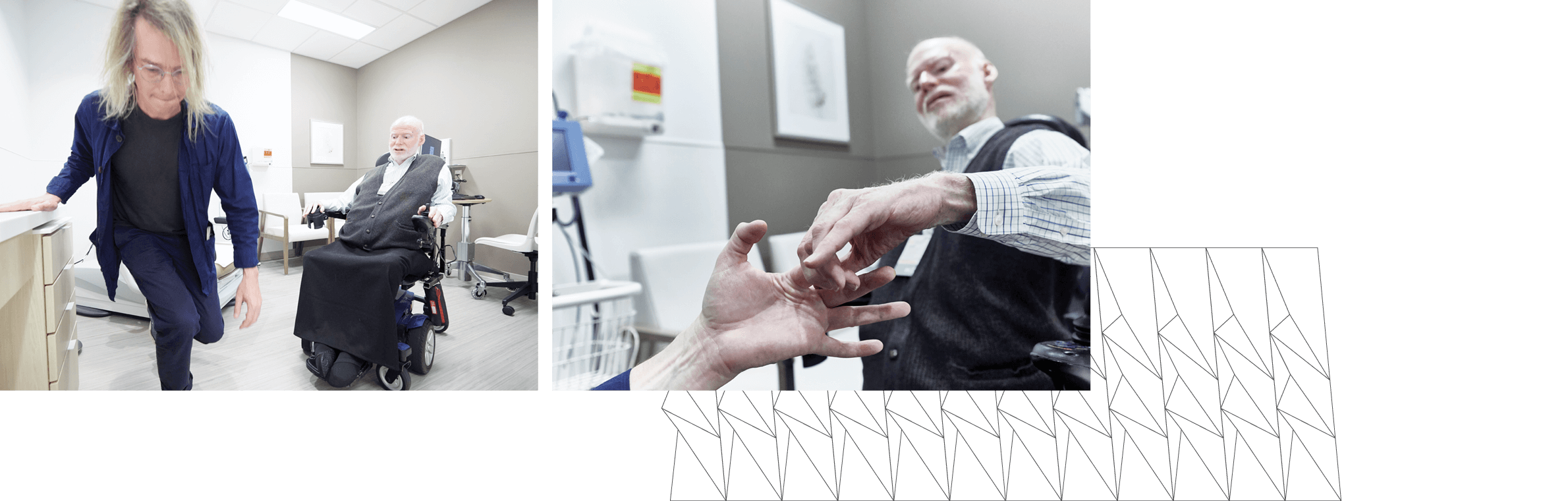

Since then, he’s had to find ways to deal with his physical limitations while pursuing his dreams. “I had imagined myself in a sheepskin jacket driving a Jeep doing house calls in the wintertime, which wasn’t going to work so well, and surgical fields were out of the question,” he says. In medical school, he carried a solid-sided briefcase so that when he fell down, he could set it on one end and push himself back up again.

But today, Quinlan, 70, is looking back at a nearly 40-year-long career as an acclaimed educator and clinician of neuromuscular disorders, which include such diseases as myasthenia gravis, Lou Gehrig’s disease (ALS), and his own.

For 35 years, he was a professor of neurology and the medical director of the neuromuscular center at the University of Cincinnati Gardner Neuroscience Institute (UCGNI). In 2021, he received the Ted M. Burns Humanism in Neurology Award, which honors “a member of the neurology profession exhibiting humanism through humble leadership, advocacy, innovation, and creativity.”

As one of a relatively small number of doctors with a disability—they make up an estimated 1% of the profession—Quinlan brings a unique perspective to his interactions with students, patients, and design professionals. He represented both patients and clinicians during the planning of the University of Cincinnati Gardner Neuroscience Institute (UCGNI), helping to ensure that the new facility would be welcoming to all.