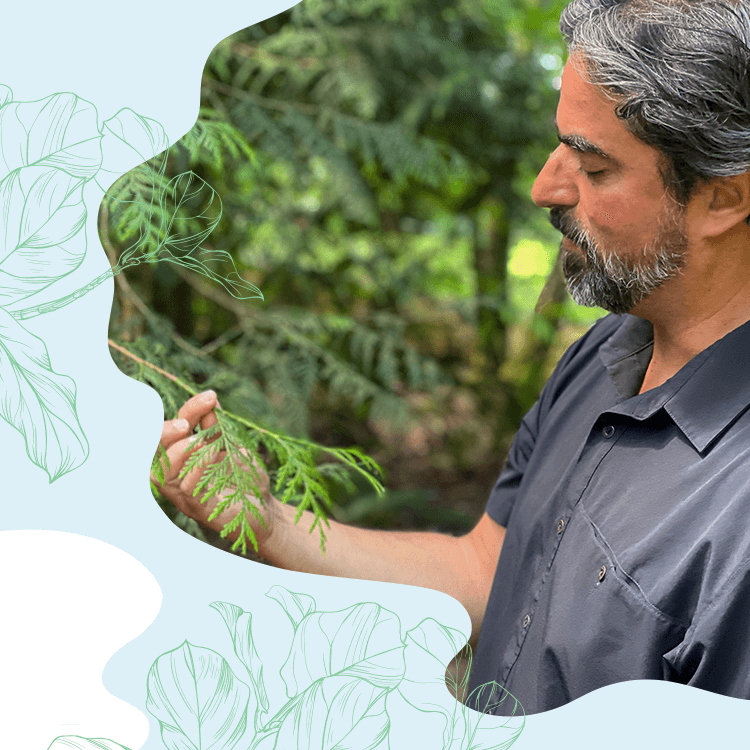

Ecologist Juan Rovalo brings new perspectives to the design process

According to the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the earth’s surface temperature has risen faster over the past 50 years than ever before. At the same time, biodiversity is shrinking and life-sustaining habitats are being destroyed or pushed to the margins. Despite humans’ impact on the natural world, Juan Rovalo thinks the built environment can shift toward a more positive future. And as Perkins&Will’s first firmwide director of ecology, he’s in a position to influence designers’ habits—and mindsets—across the globe.