In December of last year, the Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences at the University of Southern California hosted a virtual symposium, “Pump to Plug,” on the electric-vehicle future of LA. The event was prompted by Governor Gavin Newsom’s executive order earlier in the fall, requiring that all new passenger vehicles sold in the state be zero-emissions by 2035.

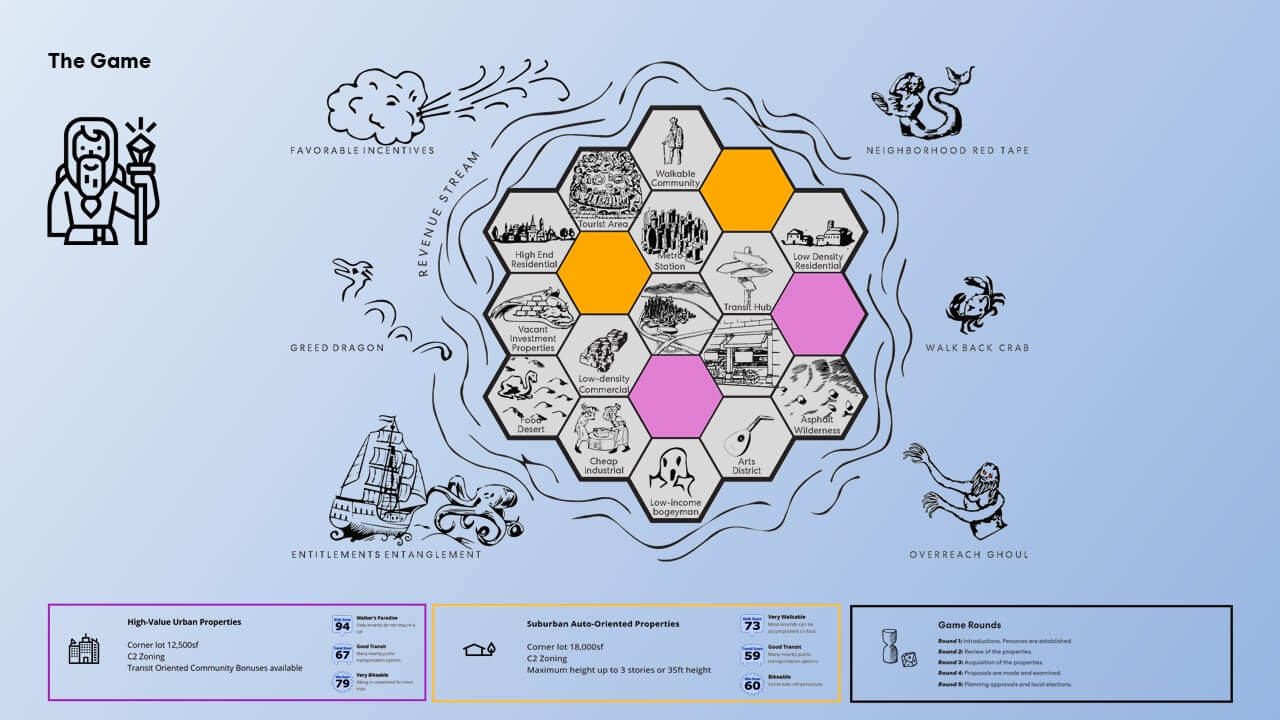

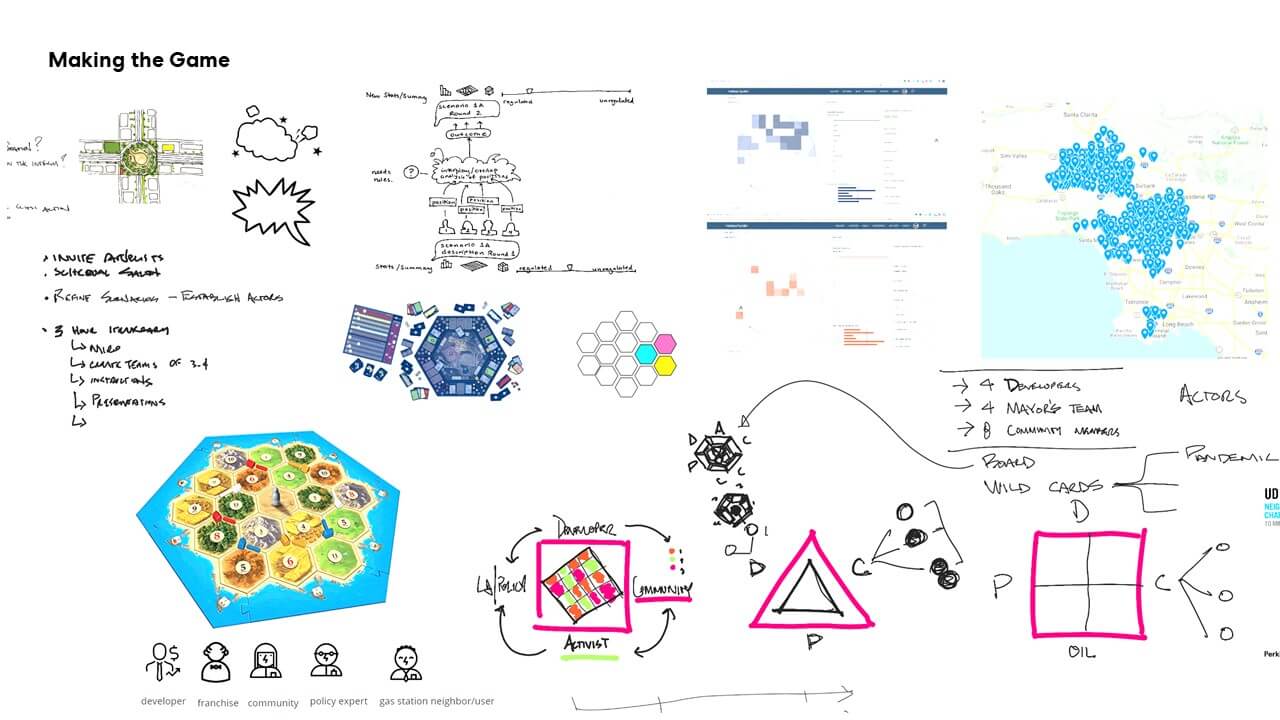

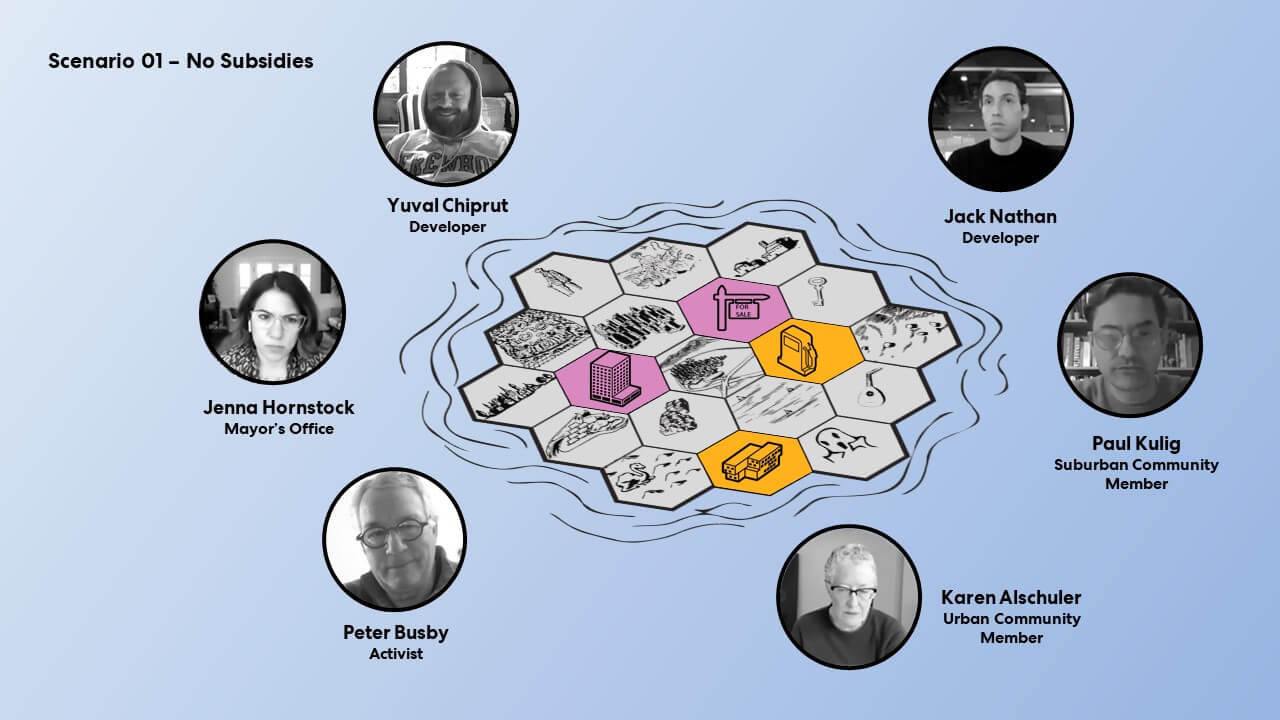

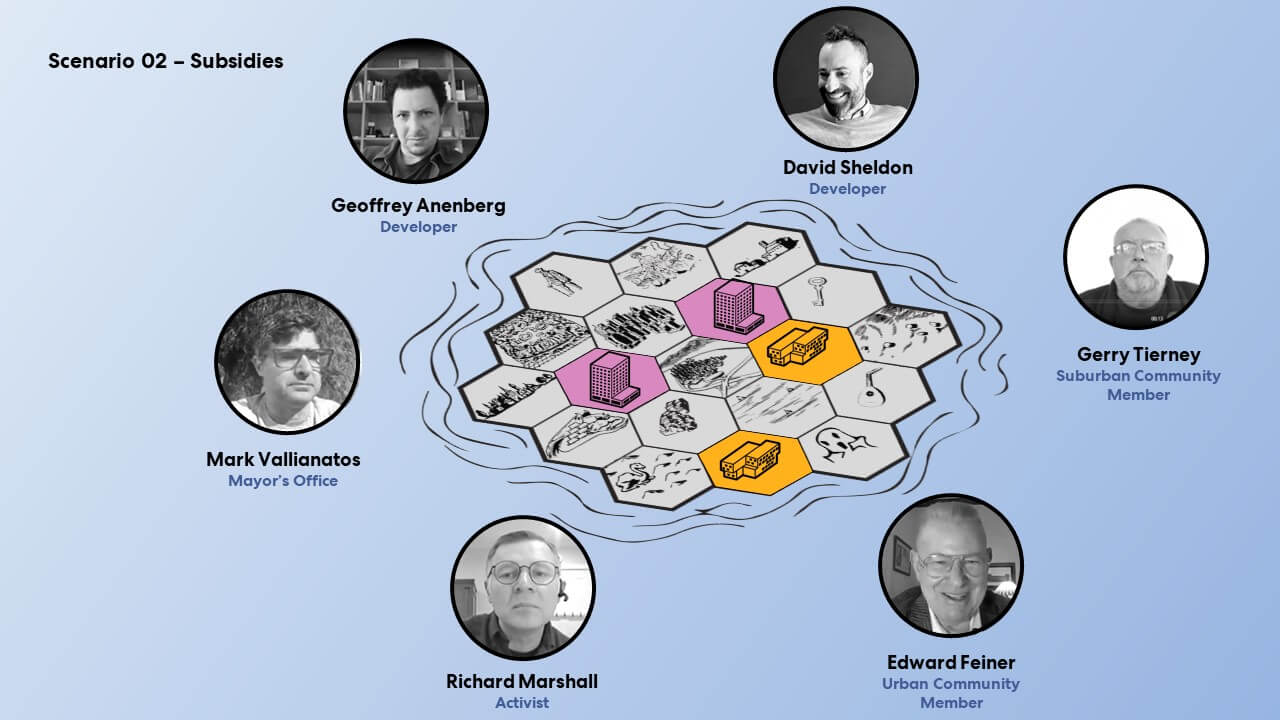

We in the LA studio were invited to participate, alongside a handful of other design and architecture firms, by developing conceptual solutions in any of three categories: The Design of Charging Stations, The Future of Gas Station Sites, and The Design of Electrified Long-Haul Trucking Depots. Our team’s approach—which gathered prominent city policy makers and developers into a D&D-style role-playing game—ultimately inspired us to propose an array of far-out concepts for the future of LA County’s 550 gas station sites.

Looking back on it, it’s hard to believe that we structured our process around the notion that our role as architects and urban designers is limited to information gathering and facilitating a conversation. Passionate and invested as we are—myself; our Urban Design Practice Leader, Martin Leitner; and designers Ashley Stoner, Ksenia Chumakova, and Kayla Ching—we almost surrendered our most critical role in the reprogramming of our city’s infrastructure.

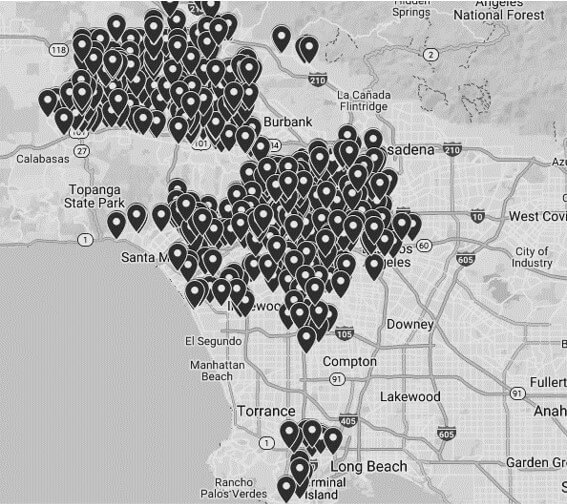

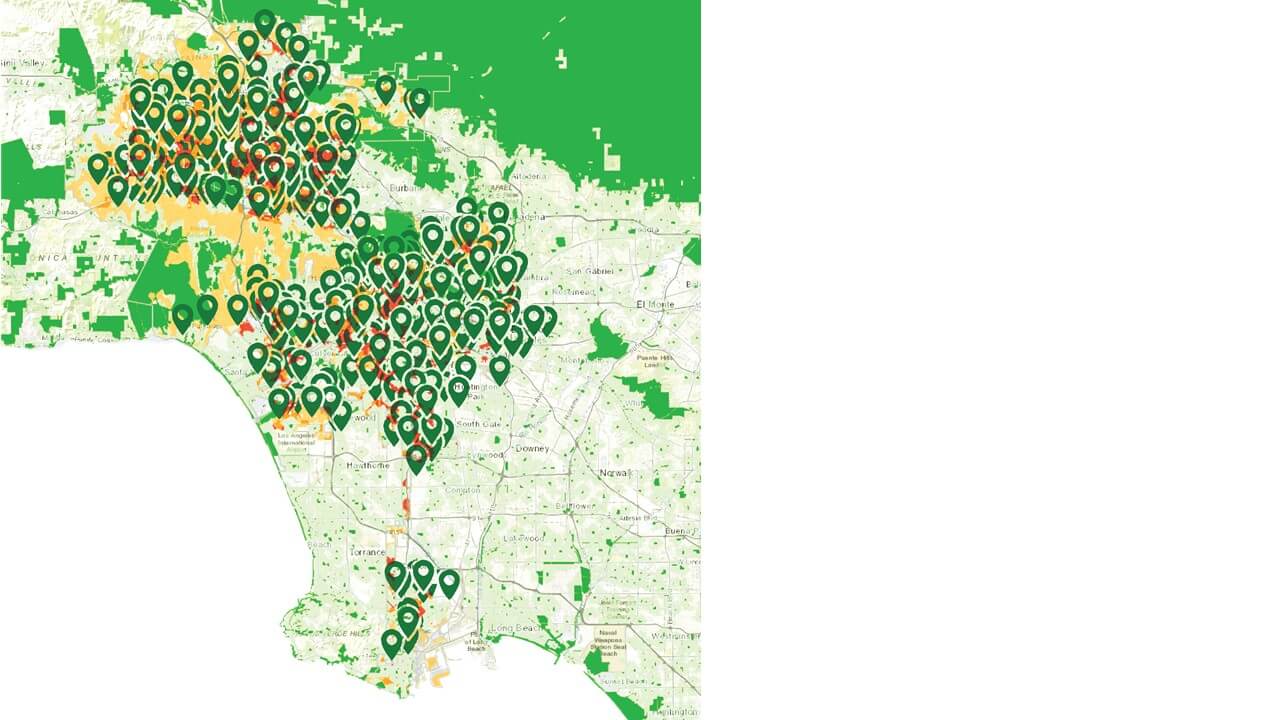

When we got the brief from Christopher Hawthorne, LA’s Chief Design Officer and director of the 3rd LA project at Dornsife, we got really excited looking at the scale of all the gas stations pinned on the LA County map.

Just think of the potential impact: reduced carbon emission, improved health, preemption of injury and death, a widely accessible quality of life. It would be a whole new LA, a whole new American city.

So we dove into the engagement. Inspired by the Radiolab episode “What If?”—which I of course heard while driving my car—we conceived a role-playing game and invited our real-life policy maker and developer friends to come roll the dice with us. Our team played their counterparts as urban and suburban community members and activists, and together we gamed out the redevelopment of some of the gas station sites.

We designed the game to ask realistic questions: What really are the possibilities for reuse on this not-at-all-blank canvas? Can those outcomes shape policy?

A few invaluable insights emerged from our two game scenarios:

- Our city’s policy makers and developers are really good at playing their roles.

- Remediation may not be the significant factor we think it is in LA.

- There will be an authentic desire and need to preserve some gas station sites.

And 4: If we make the game and play it by all the rules we know, our outcomes will just be more of the same in our city—however thoughtful and context sensitive we design the redevelopment to be.

It was our Global Design Principal, Peter Busby, who got us to this last one. As we wrapped up the discussion at the end of the engagement, he made the following statement:

Our plan had been to play the game, document the results, and present our findings at the symposium. But as Peter’s closing remarks echoed in our heads, we began to realize that we hadn’t even thought to dedicate a role for the visionary in our game.

Christopher Hawthorne had organized “Pump to Plug” to create a platform for us to be visionary, and we brought to the table some of the visionary players we regularly see at City Council meetings and public engagements. But for all the creativity and design intelligence that went into the engagement, we had missed something essential for inspiring the transformative policy we so desperately need.

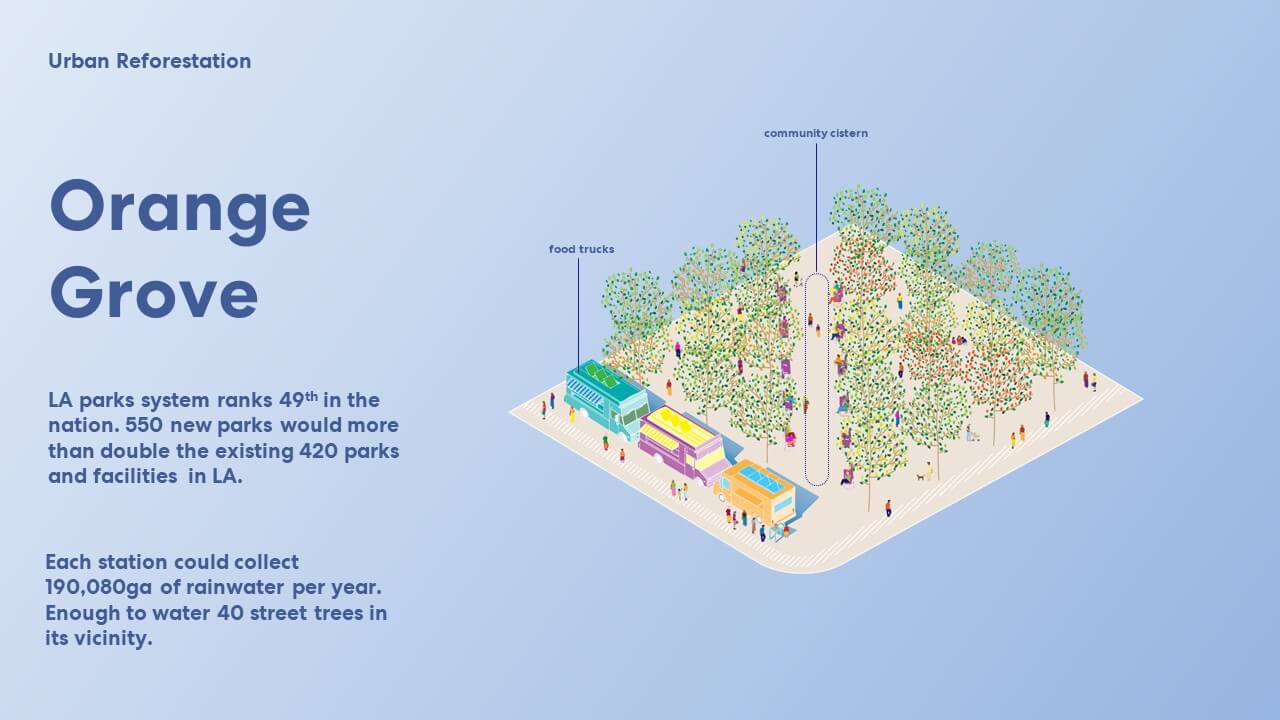

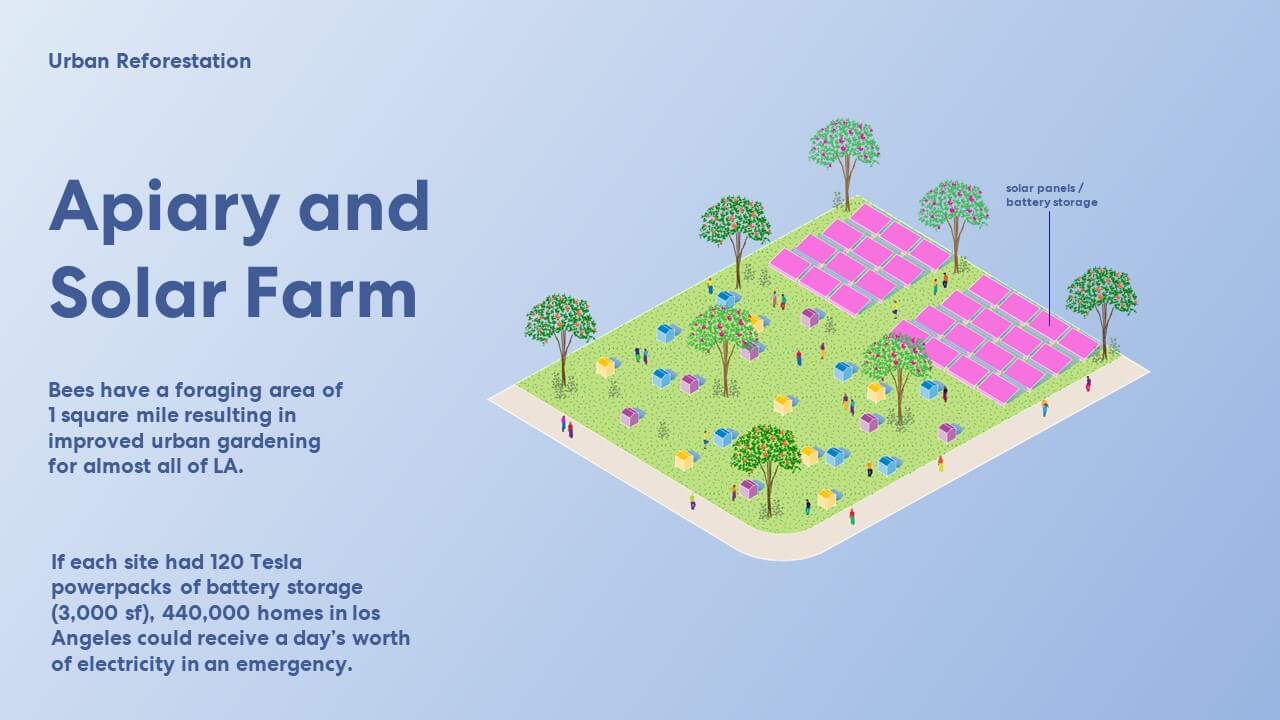

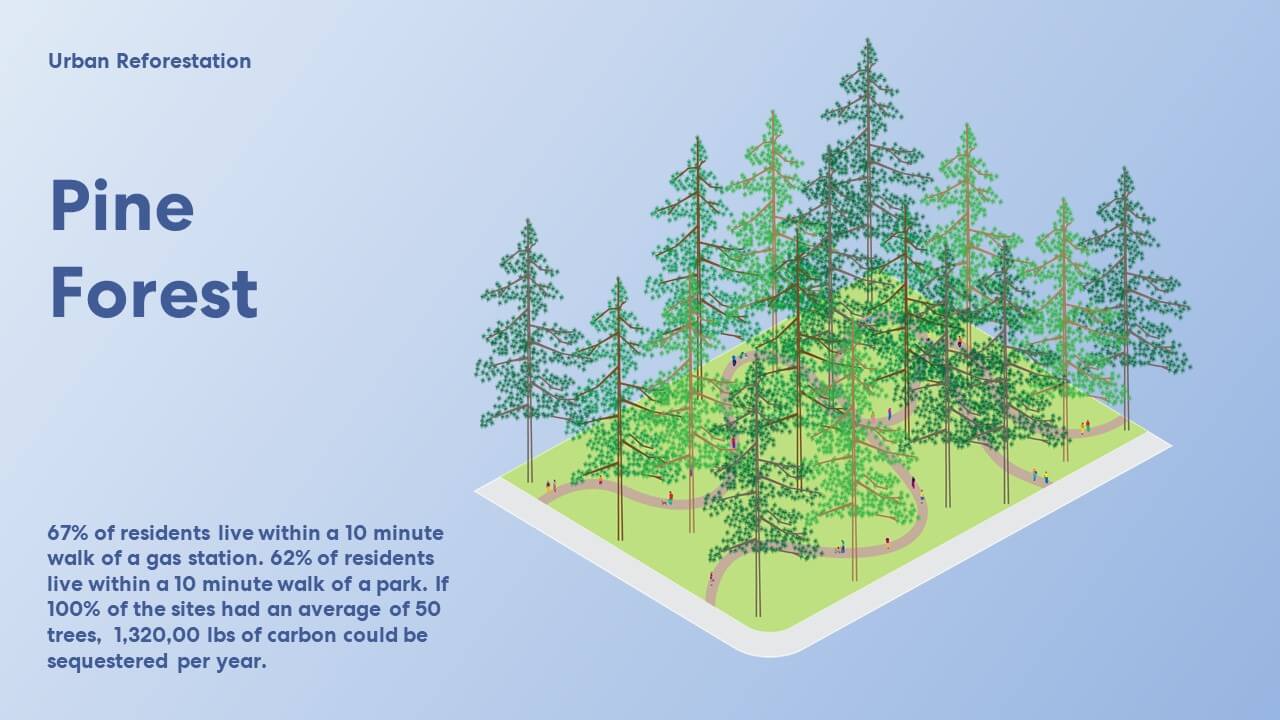

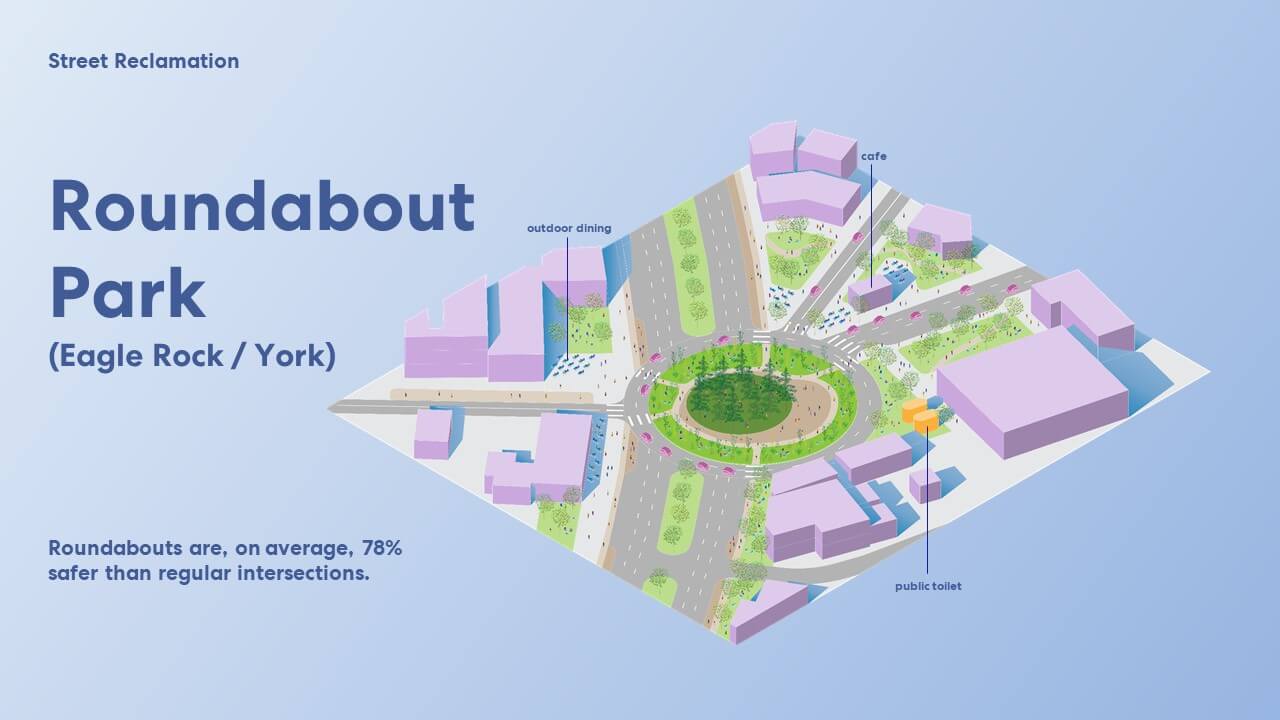

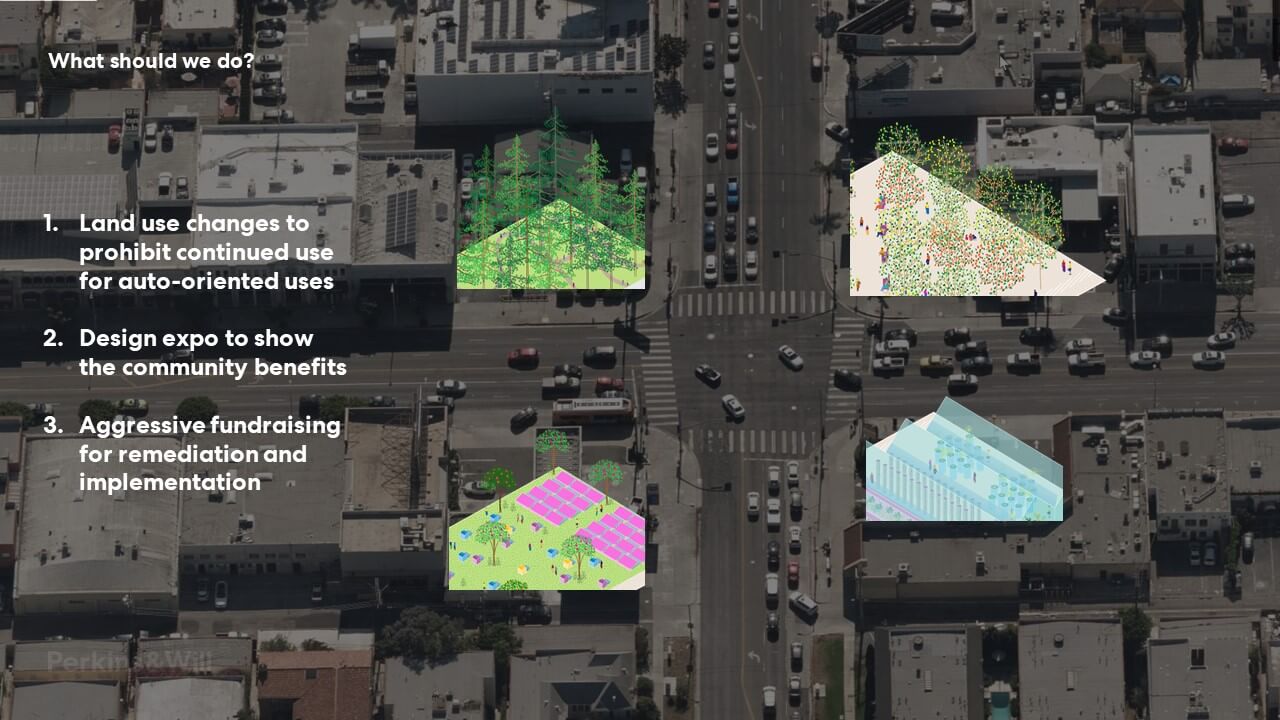

So we threw out our thoughtful development schemes and stopped being realistic. We said, “Let’s be free to imagine what we’d like our city to be.” The second phase of our process kicked in, and we dove into a much more aggressive reimagining of the character and urban fabric of LA. What can we do with 550 gas stations across LA County? Urban reforestation. Social infrastructure. Housing equity. Street reclamation.

We let ourselves dream big about the LA we want for ourselves and our city’s communities, not because we want an apiary, Amsterdam-style streets, a pine forest, or a half-pipe at every corner—although that would definitely be cool—but because a city needs visionary creative people to capture the imagination of the public.

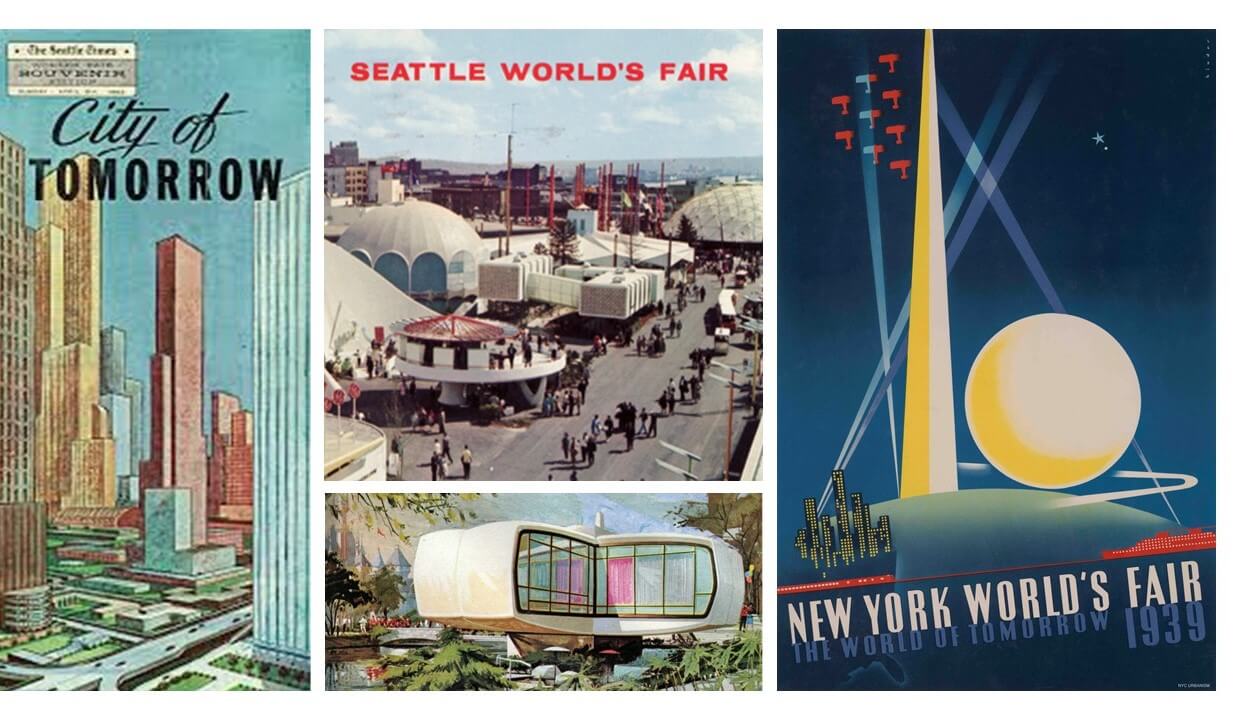

This is not pie-in-the-sky optimism. Large-scale restructuring is possible, and it has been done before. In the middle of the twentieth century, it was the automobile industry that captured the imagination of the public, with visions like GM’s Futurama at the 1939 World’s Fair and Disneyland’s Autopia in 1955 (where the cars still run on gas). Maybe more than any other American city, LA embraced the optimism the auto industry was selling and the idea that car culture is integral to the character of Los Angeles. It’s not untrue. We love our cars.

We also hate our cars. When you overlay the map of pins where all the county’s gas stations are with the Trust for Public Land map showing need for access to green space, there’s a clear, if not surprising, correlation. More Angelenos live within a 10-minute walk of a gas station than live within a 10-minute walk of a park. That puts us at 49th among the parks systems of the hundred largest cities in the U.S., according to the same Trust for Public Land. And that’s nowhere near where we should or could be in terms of park access.

For better and worse, architects like Norman Bel Geddes (Futurama) and Eero Saarinen (GM Technical Center) conspired with the automobile industry to make a built reality out of its dreams of the future. We architects can do it again, but we need to claim a visionary seat at the table, and we need to do it from the place of public interest.

Between all the postcards is our city. If we imagine a Futurama that’s sponsored by our elected leaders, what will we dream up then?