When it comes to passenger rail, North America is moving at much slower speeds than most of the developed world. But that may soon change. Several groups across the continent are planning to connect cities tied together by region and economy with high-speed rail—specialized passenger trains that run on dedicated tracks at cruising speeds of up to 220 miles per hour.

To highlight just one, consider Cascadia Rail. The State of Washington, with support from Oregon, the Province of British Columbia, and a host of private companies located in the region, want to build a high-speed rail line linking the 345-mile Cascadia Innovation Corridor, which spans Vancouver, British Columbia; Seattle, Washington; and Portland, Oregon. Boosters say it could swiftly and safely cycle 32,000 people an hour through its various stations. This would be a welcome pressure release on the traffic sure to accompany the 4 million people the Washington State Department of Transportation expects to move to the area in the next few decades.

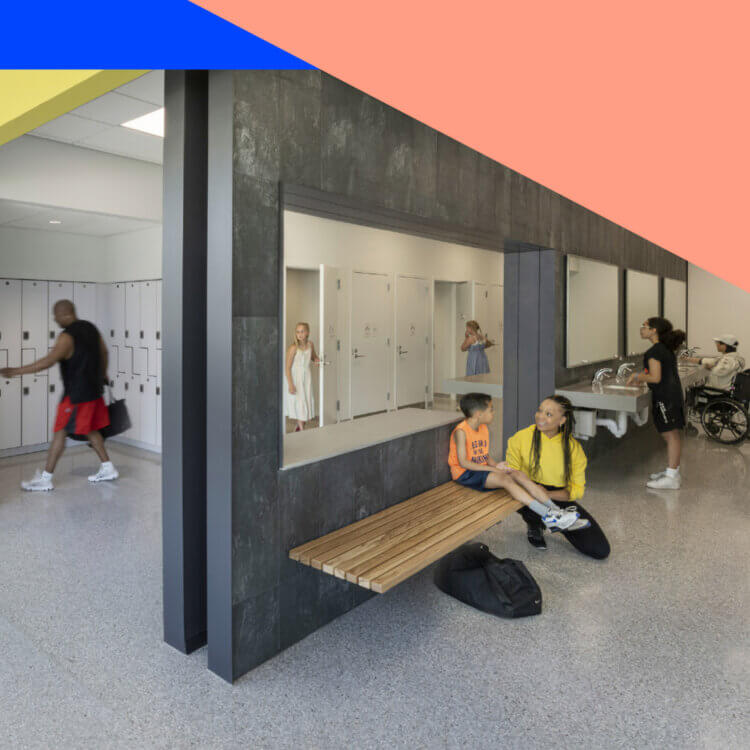

While high-speed rail doesn’t entirely reinvent passenger train travel, there are unique considerations that come along with developing these projects. “Cascadia follows along with the 35 or 40 years of work that have been going on in the region,” says Oregon Metro Council President Lynn Peterson, including existing light rail and high-density, mixed-use stations. “The difference is, the higher the speed, the longer the spacing between stations, and the more volume coming off. So, you’re trying to accommodate what you can do with the land use on a scale that’s, well, different.”