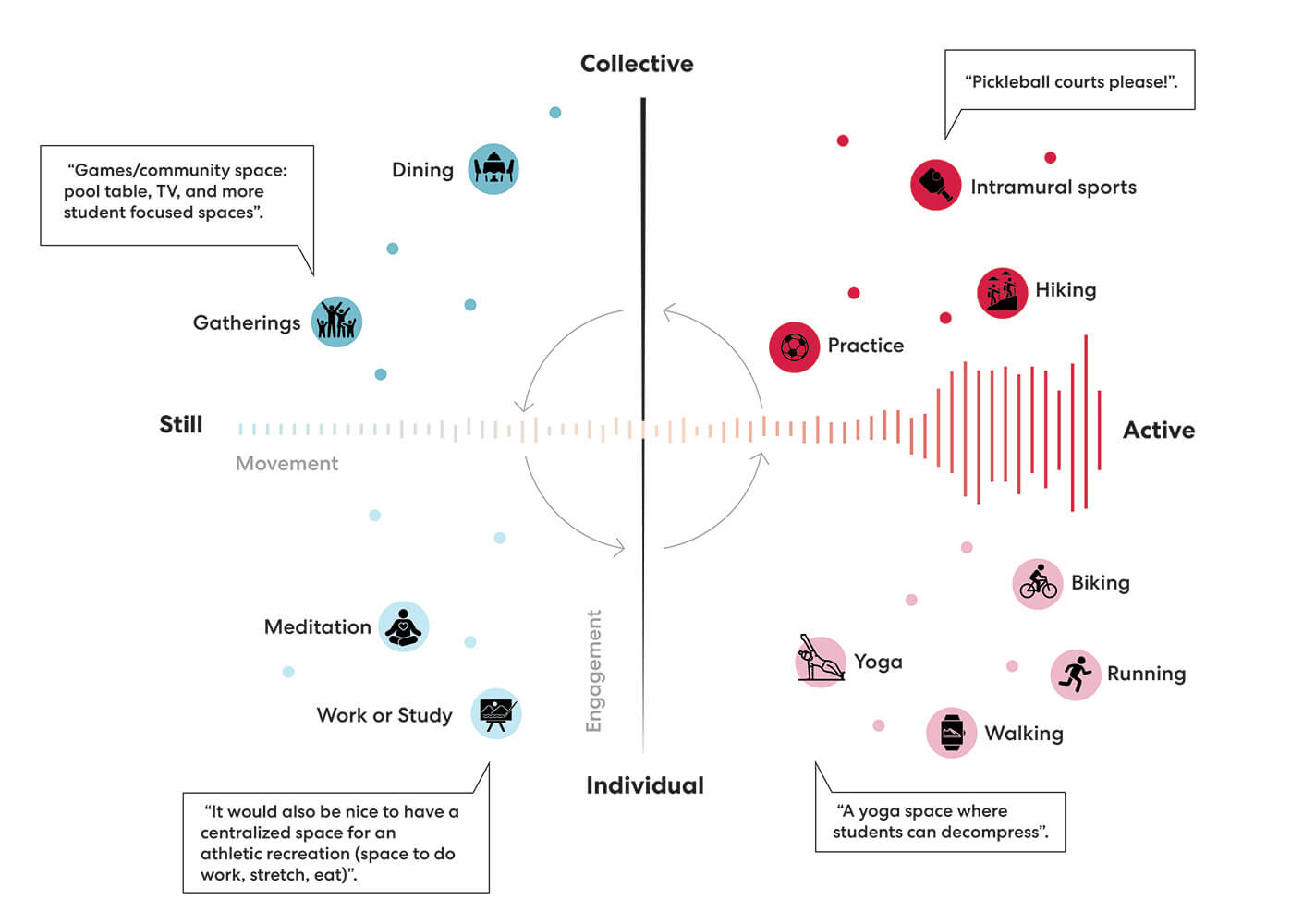

On many college campuses today, well-being is addressed through a set of standalone services: gyms, health centers, athletic fields, and support programs. While these facilities are often well-equipped, they can remain physically and functionally disconnected from students’ daily routines. The result is a narrow approach to well-being—one that emphasizes physical fitness and clinical care but overlooks everyday needs, such as the ability to decompress, share a meal with friends, or sit in silence and feel safe.

What if, instead, well-being wasn’t thought of as a destination or a facility, but as a condition that flows through the campus experience? What if it were less about services students must seek out and schedule, and more about an environment designed to support balance, connection, access, and care throughout the day?