Do you take design inspiration from other arts, sciences, or professions? If so, which ones and how do they influence your thinking?

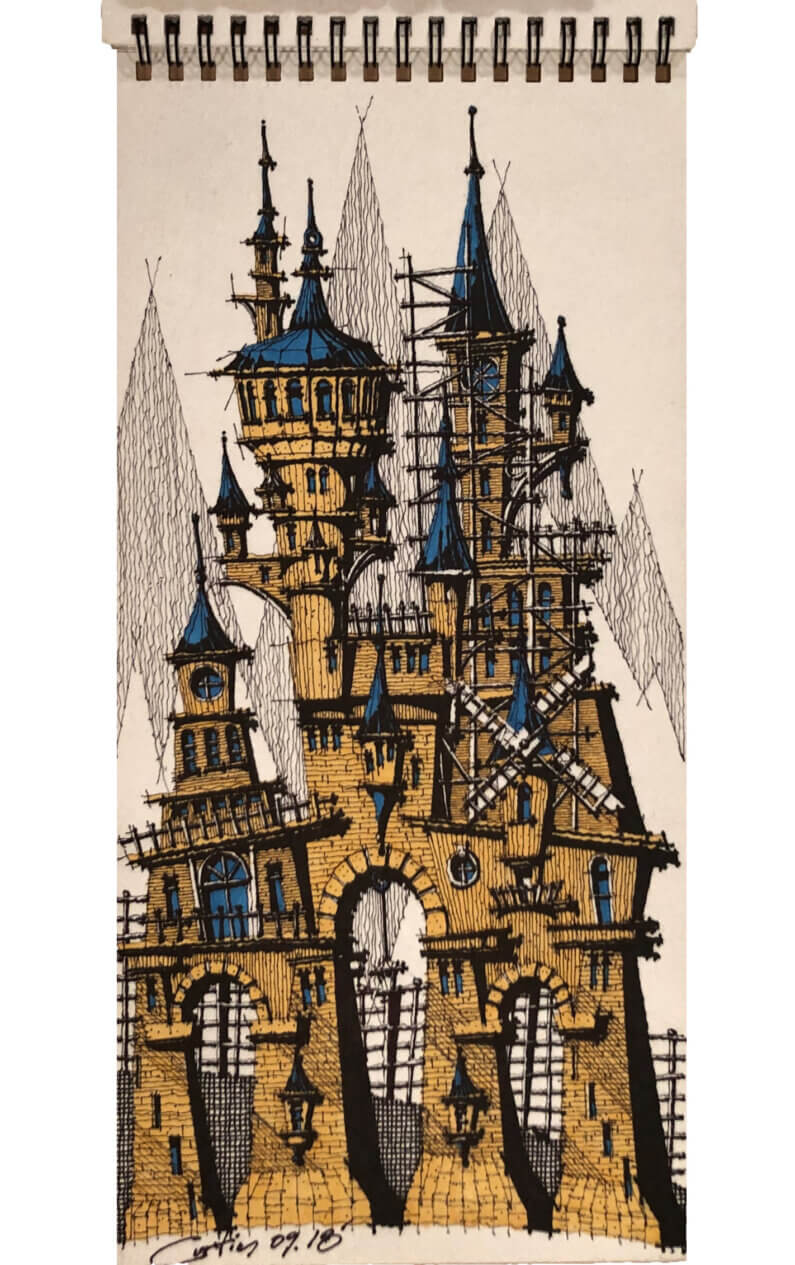

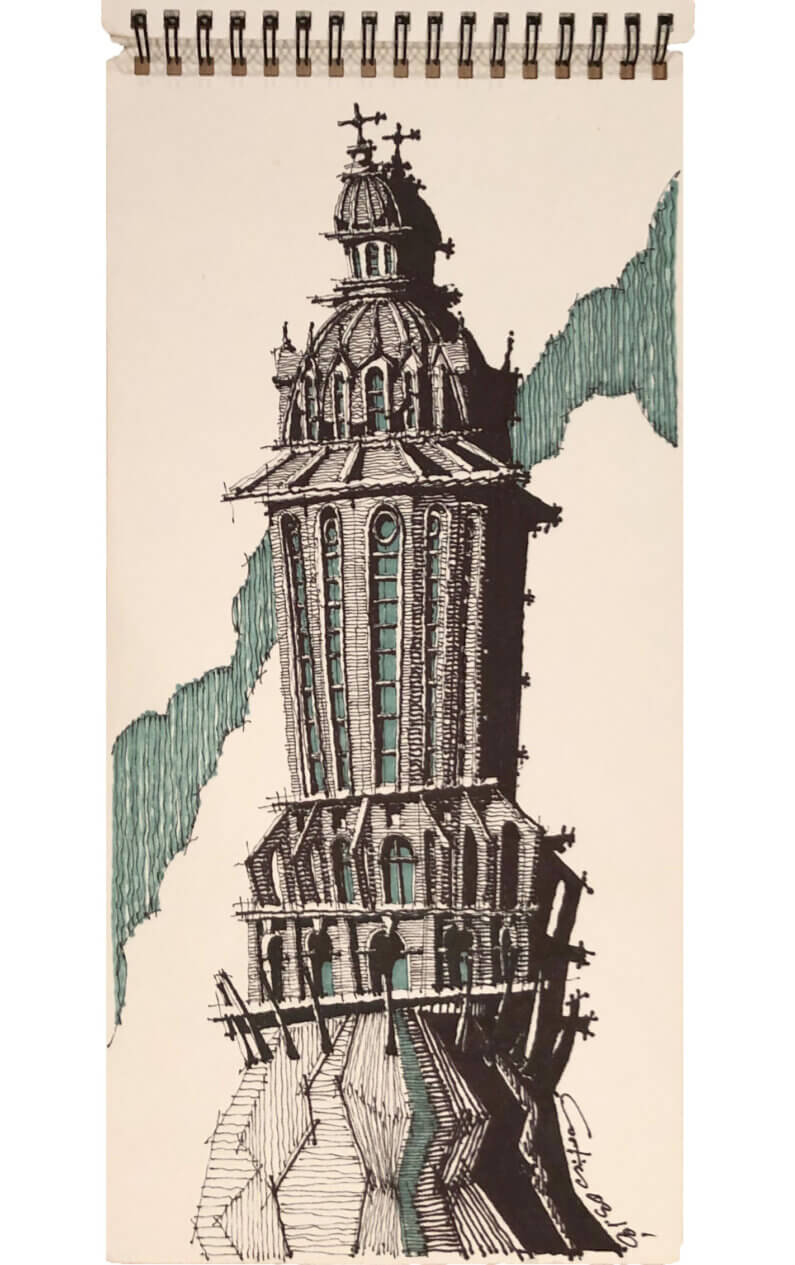

Inspiration, for me, is never a single thought—it’s a collection. I draw from the quiet precision of science, the emotional charge of art, the rhythm and breath of music, the contours of topography, the beauty of land and sea, the soul of place, and the evolving intelligence of technology. Together, they provide a different way of seeing, a different lens through which the world reveals itself.

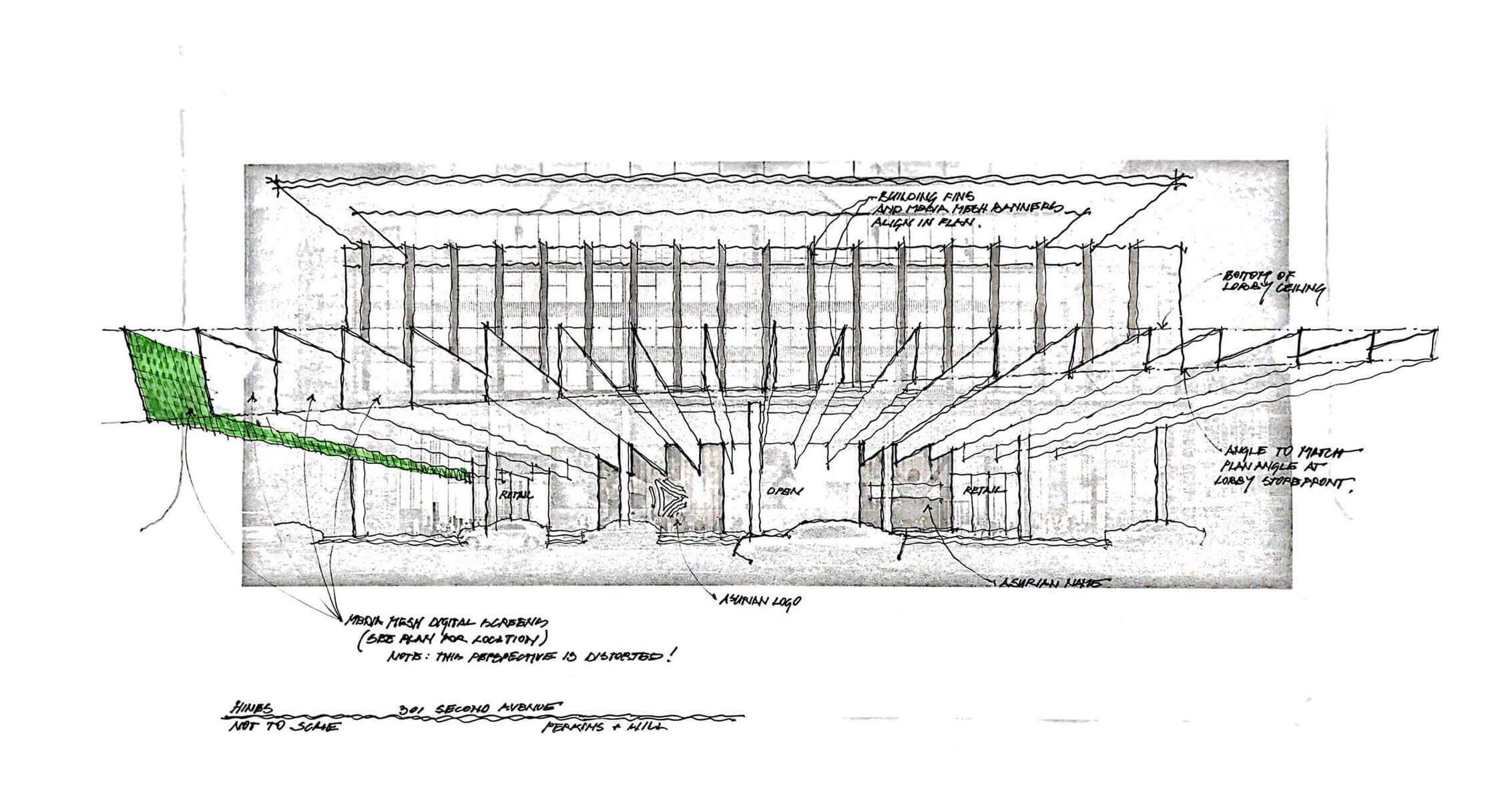

In branded environments, these references aren’t decorative, they are deeply rooted. They infuse the work with a deeper meaning, giving us not just a narrative to tell but a design voice and language to speak. When the rationale of physics collides with the emotional expression of painting, when a musical refrain finds its echo in material rhythm, when a landscape’s geometry becomes a framework for form and flow, our environments become more than experiences, they become stories you can walk into.

How do you respond to criticism—whether from clients, peers, or the public?

I welcome criticism. I’ve come to understand it not as a blunt force to endure, but as an invitation to listen more deeply. In the world of brand and environmental design, where every gesture is intentional and every detail carries narrative weight, critique is simply another form of understanding. It reminds me that our work is alive, subjective, and open to interpretation.

Not every expression we create will resonate with every audience; nor should it. What matters to me is that the design’s essence is rooted in intention, research, and a devotion to meaning. The solutions must rise from a clear understanding of a client’s ambitions, the truth of their identity, and the experiences their communities are meant to feel when they encounter my work. These stories are never invented; they are excavated from history, mission, values, and the subtle qualities that differentiate one brand’s voice from another’s.

So when critique arrives from clients, peers, or the public, I try to hold it with curiosity rather than defensiveness. I look for what it reveals: misalignments, opportunities, new angles of approach. Because branded environments, whether physical, digital, or emerging in artificial realms, are inherently subjective spaces. They ask us to balance vision with empathy, narrative with clarity, beauty with utility.

This is why I anchor my process in discovery, in listening, in building a framework that is grounded in human experience. When criticism meets a foundation like that, it becomes less about right or wrong and more about refinement—about sculpting the work into something truer, more resonant, and more beautifully aligned to connect with its users.