Chris Hardie: An Architect Bridging East and West

Ten years ago, Chris Hardie was invited to visit China to work in Tongzhou, a suburb of Beijing. At a time when foreign architects were traveling to the country pursuing the bold projects that have come to define so many Chinese city skylines, Hardie observed others like him, wading through train terminals with young translators, shaking hands. He had planned to stay for one month, but now, after one decade practicing in the East and one in the West, the Scottish-born architect is at a crossroads in his career, and he’s wondering, what’s next?

“I’ve always been drawn to a more authentic simplicity in design,” Hardie says. He began his undergraduate architecture education at the Scott Sutherland School of Architecture in Aberdeen, Scotland, which he describes as a “very technical school.”

“I remember going to my advisor in my second year, looking at him and saying, ‘I don’t know if this is for me.’ But then I went to Chicago, to the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), and my perspective on the practice of architecture completely changed.”

Hardie’s years at IIT were pivotal: His decision to transfer marked his first time leaving Europe after growing up in rural Scotland, his first time seeing a skyscraper, and his first time seeing architecture as design, rather than engineering. “This exposure opened up the profession for me, but also reaffirmed a lot of the core principles I’d brought from Scotland,” he reflects. Studying under Ila Berman and alongside guest critics Chris Wilkinson and Jim Eyre, followers of the British High-Tech movement, Hardie found his stride, and returned to the U.K. to pursue his geometric, material-based designs.

Diving into the European design world, Hardie took opportunities at firms that he felt shared his affinity for authenticity of form. Now, he’s been overseeing design at the combined Perkins&Will/SHL Shanghai studio since 2010. Hardie has crossed many borders—political and ideological as much as geographic—but asserts that his design philosophy has stayed fairly constant.

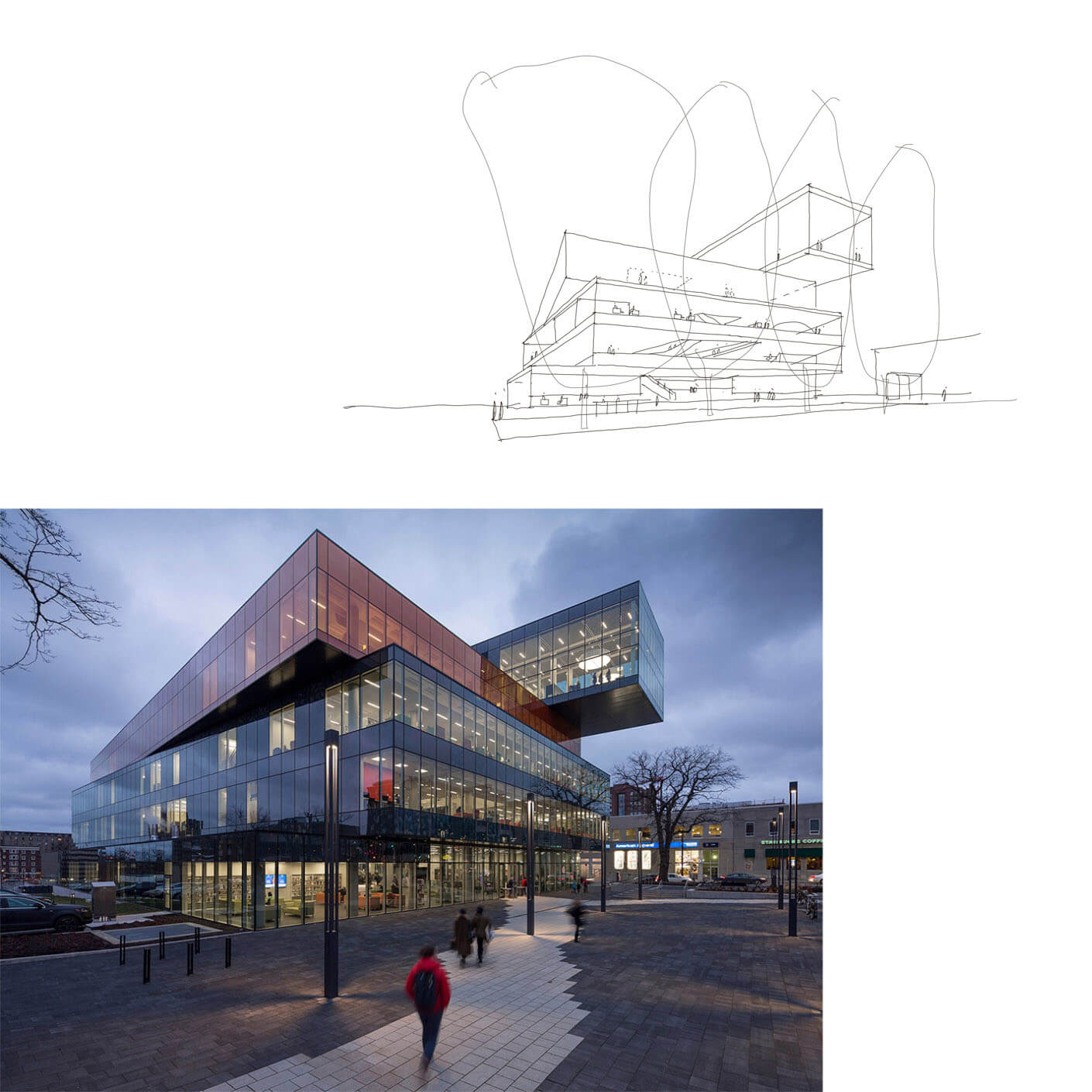

Hardie favors the use of architectural diagrams—visuals that, in simple terms, pictorially describe big, abstract ideas, particularly at the beginning of a design process. While these images are often accompanied by captions, or bits of dialogue delivered by Hardie himself, the verbal aspects of his English communications are methodically considered, each word and phrase chosen for its ease of translation and directness.

“I like simple things, and that goes a long way when you think of architects as communicators,” he says. “In China, I am communicating complex and quite permanent design ideas to people whose language I don’t speak. Everything has to be drawn, delivered, and designed with an incredible amount of intention. And I’ve become very attuned to that.”

This self-discipline has taken Hardie and his Shanghai studio to new heights.

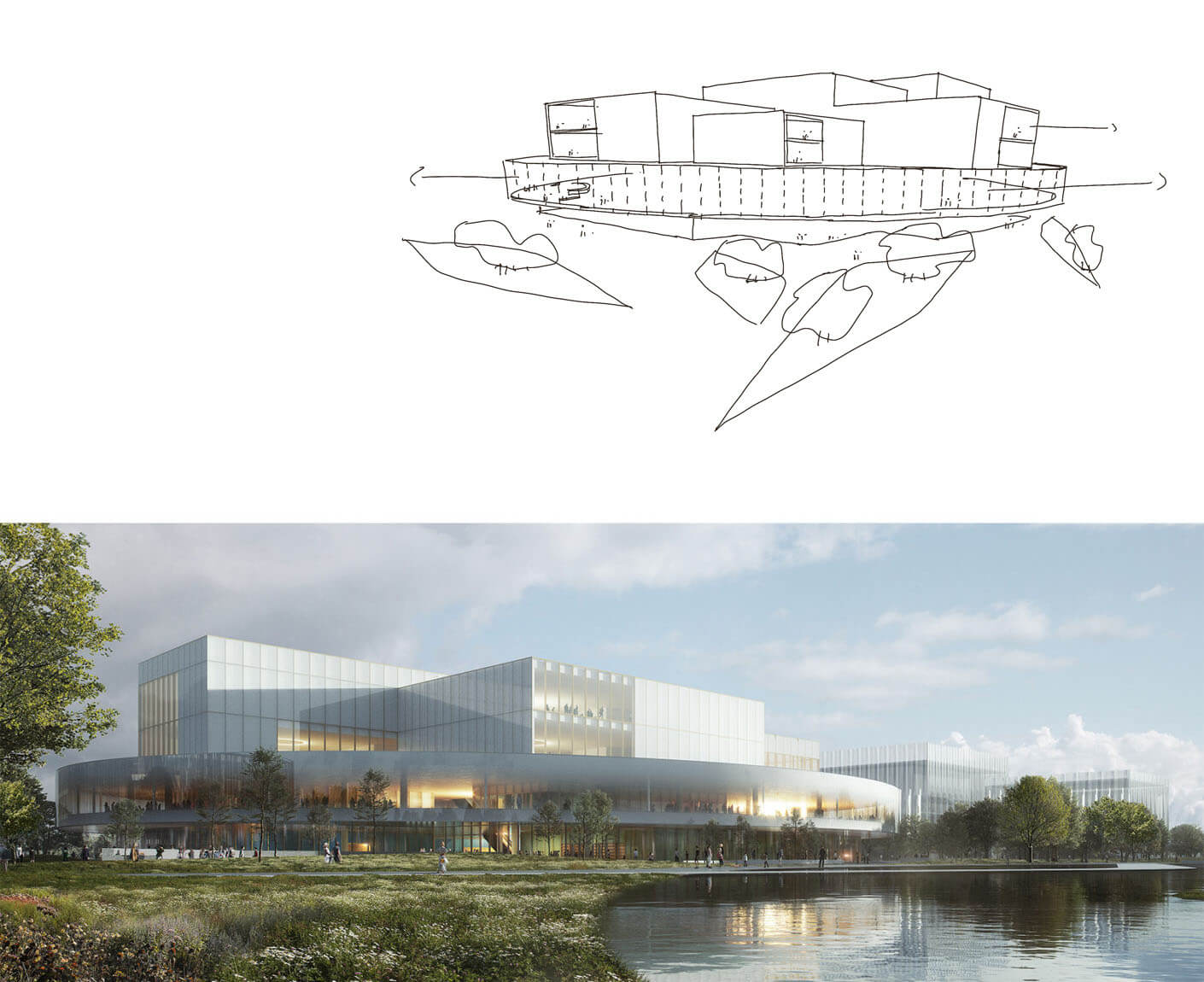

Usually, the designer’s favorite projects begin as competitions, where the design process is more free-flowing and driven creatively by the studio. Many Chinese cultural projects start this way, as they are run and overseen by the government rather than private clients. One of the designer’s current projects is the Shanghai Library East, unfolding in the city’s largest park and on track to be one of the largest libraries in the world.

Hardie observes that his studio is at their best when the team is relaxed, inspired and collaborative in their approach to new competitions, and this library was no different. “This is a significant project not just due to its size, or its site, but also because it’s a center of knowledge. Here, we let the symbolism guide our thinking.”

The team took into consideration a myriad of factors, but most importantly the cultural heritage of Shanghai, evoking the library in the park as a scholar’s garden, with its center being the Gongshi, or Scholar’s Rock. “While my vision for the design was very pure in its geometry, I was able to place it within the cultural context of the site and the country, which is an exciting thing that design allows you to do.”

As design director, Hardie sees the bigger picture: juggling all the projects the Shanghai studio is working on at any given moment. “It’s almost more like I’m a conductor of an orchestra than a designer,” he says. Especially when big projects, like his Shanghai Library East, take five or more years to complete. While in some professions you can see the results of your labor in minutes or days, Hardie’s work pays off in the long run. “At the end of a project, on opening day, I remind myself that we’re the creators of such lasting icons to our moment or to specific places. I find that many of our Chinese clients are interested in symbolism: aligning their new 21st century building with the long history of the country. Here, they’re not interested in fads or novelty materials. They see their architecture as investments in a culture that has continually remained alive.”

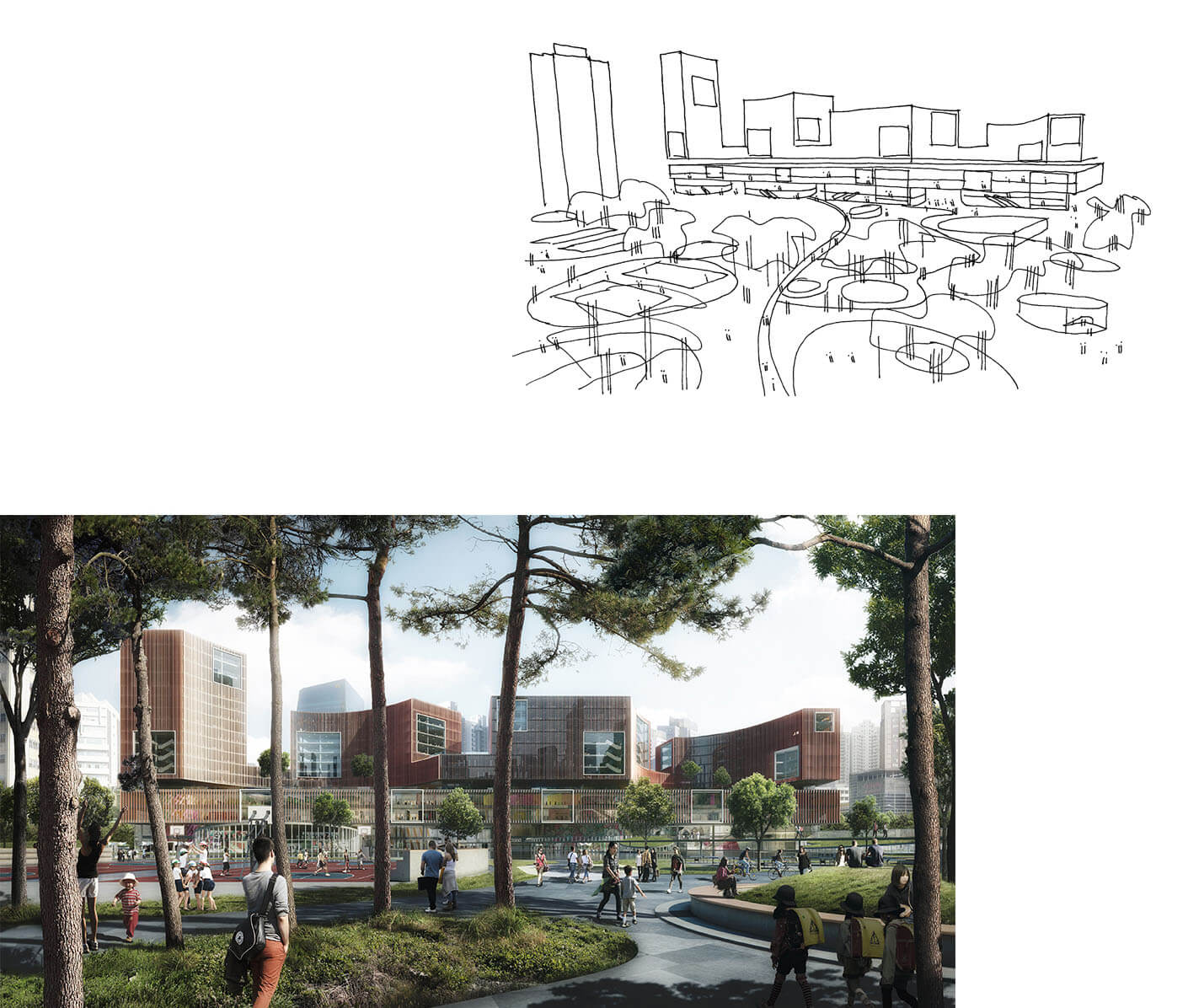

Hardie’s style, stemming from his education in Scotland and Chicago, has retained its purity. Even as he continues to refine his use of bold, geometric forms and authentic materials, he’s not afraid to assert what he likes, or what speaks to him as a designer.

“In our studio, we often brainstorm ideas by first looking at art. Paintings and sculptures, and artists in general, are so free in their thinking and expression. In architecture, we as designers often feel like we have to disguise our good ideas behind a fabricated value system—whether that’s a specific story, a system or pattern, or someone else’s idea of what’s legitimate. Looking at art inspires me to refresh that auteur mentality that we can often lose when pressured to align our idea with some other external expertise.”

Hardie and his team often refer to works by artists like Donald Judd, whose minimal yet evocative forms are highly architectural, and shape the space of their galleries in ways that make them seem almost like architectural interventions. And while Judd returned to similar iconographies over and over again—the cube, or his stacks—each time they were somehow fresh, somehow reinvented.

That’s how Hardie views his architectural output. “We speak about new projects in terms of our old projects quite a bit, as it’s a starting point that guarantees everyone is on the same page,” he says. Hardie and his team love the flexibility of rectilinear spaces, and expressing their pure geometries on the façade. “But sometimes I can get frustrated when someone says, ‘wait, we’ve done something like this before.’ Obviously we don’t want to repeat ourselves, but really, the danger is repeating something without improving it.” This constant refinement and self-assessment is what marks Hardie as a designer, as well as a leader. “My team works well when we’re self-referential, but with the knowledge that we’re always working with progress in mind, to truly see the full potential of an original idea, or get as close as we can.”

Now finding himself at this poignant midpoint, between two career-changing decades, Hardie is reflecting on what that means, and also, what comes next. While the East/West idea is just a binary, the knowledge of a different culture, government, or people is invaluable for an architect, especially one as international as Hardie. The young designer knows that there’s so much more to come, and to build. “Who knows, maybe next, I’ll find somewhere in the middle.”