Gautam Sundaram and the Choreography of Master Planning

For principal Gautam Sundaram, solutions are found by searching for simplicity. The leader of Boston’s Urban Design practice grew up in India among a family of engineers, expected to embrace a career in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM). A self-identified “black sheep,” however, Sundaram chose to forge his own path—one more aligned with the fine arts and inspired by his love for travel. He was accepted to the University of Pune, one of the top architecture schools in his home country, where he found his passion for weaving history and social purpose.

Sundaram was greatly influenced by his studio’s travel program, which gave him a chance to engage with the myriad of cultures that call the Indian subcontinent home. Seeing India’s architectural canon firsthand, Sundaram became enamored, almost accidentally, with the many variations of vernacular architecture throughout the provinces. One day when his studio was on a trip to Jaisalmer, a city near the border of India, he got lost. He was in unfamiliar territory, and he didn’t know the local language, either. In his attempt to orient himself and find his way back to studio, he was forced to observe his surroundings more carefully than ever before.

After graduation, Sundaram was underwhelmed by commercial post-grad work. “I wanted to find the soul of a site,” he says. One night, he remembers, he came home to his family after a long day of work, and his mother asked about his frustration. He responded, “I like what I do, but I’m not doing what I like.” That was a pivotal moment that inspired the emerging designer to change course and come to America to study landscape architecture. “Education,” his mother had said, “is always the answer.” This motivated his decision to study landscape architecture and urban placemaking, and a new chapter in the U.S. unfolded.

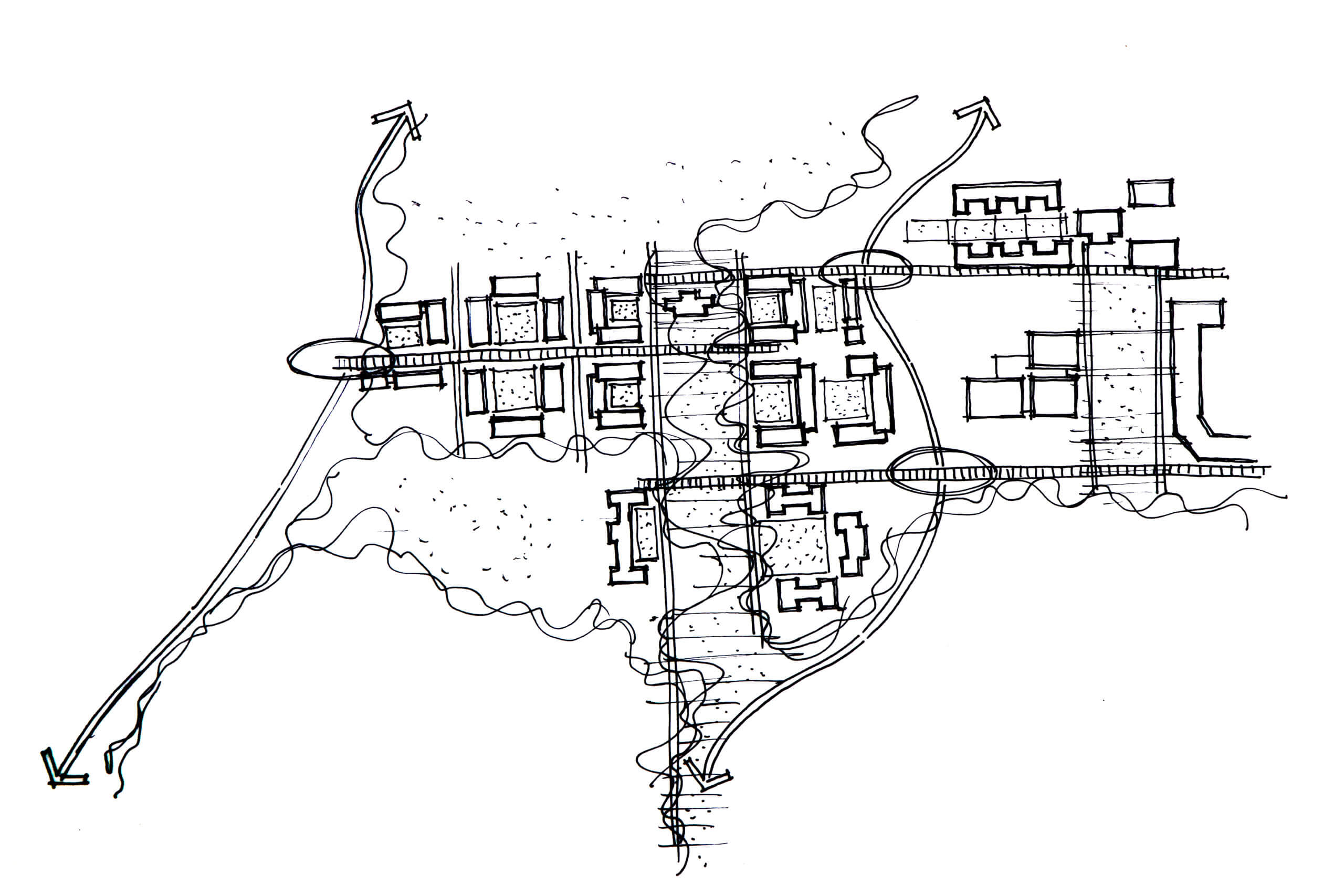

At the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Sundaram found many capable mentors and colleagues with established viewpoints yet he kept coming back to a fundamental question: “What are we trying to solve here?” While adjusting to life in Boston, the young designer found himself zooming out, and focusing again on the difference between clarity and noise in work and life. He engaged his projects through thorough historical research, skimming records and old maps until the story of the place came through. Since then, he has been able to successfully unite even the largest, most diverse teams by finding solutions based on site history and cultural traditions–human-centered touchpoints that crystalize a collaborative vision.

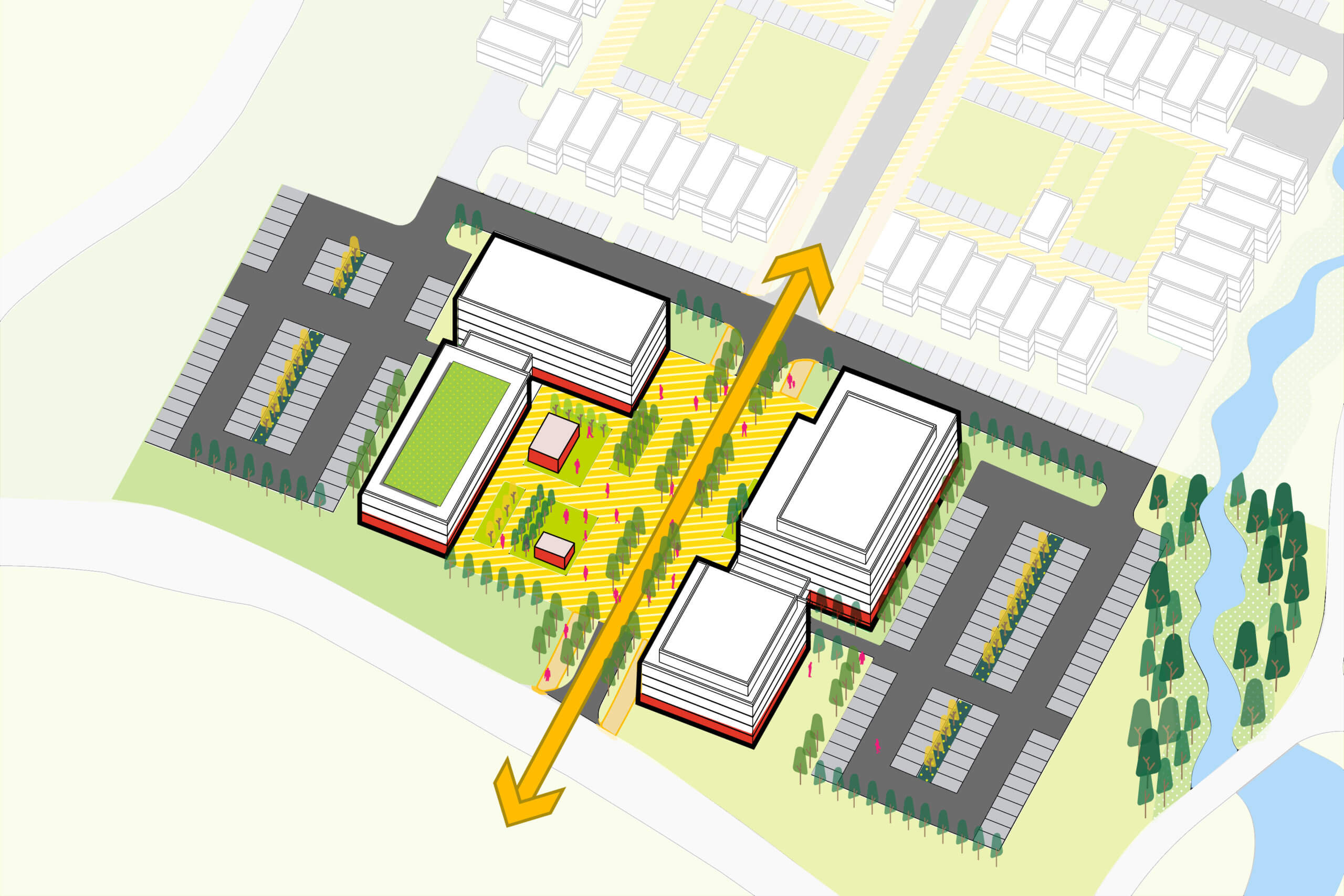

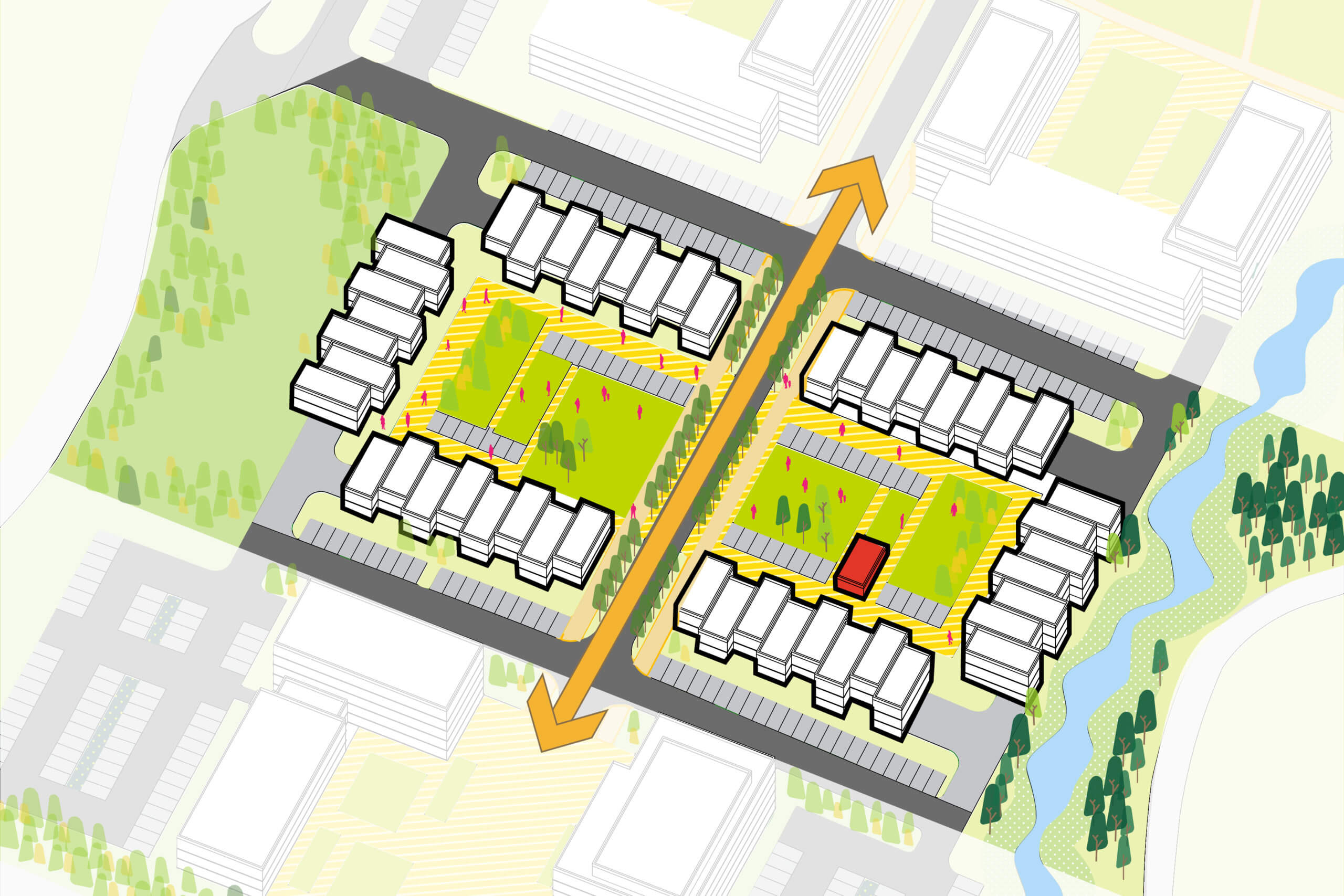

Sundaram’s preferred method of work is the master plan, a medium that bridges global design issues and the needs of unique clients, cities, and public works. A favorite project that excavates history through design was his work at the University of Virginia (UVA), one of the oldest academic institutions in the U.S. Sundaram’s task was to bring community cohesion to the sprawling campus. Home to over 50,000 students, it had recently taken on several new “satellite” campuses.

Particularly present on the North Grounds, these satellite identities that had evolved overtime to accommodate the growing campus seemed inevitable at the onset. Yet through Sundaram’s careful research and historical grounding, he yielded a solution: UVA’s Great Lawn is an original Thomas Jefferson design element, and one of most central and unifying aspects of the campus. To better incorporate the satellites, it seemed only natural, and simple, to take this core idea and apply it to the school’s modern footprint.

The central lawn was the first historic site decision for UVA grounds, so Sundaram felt drawn to that piece of history, and let it inform the future of the contemporary design.

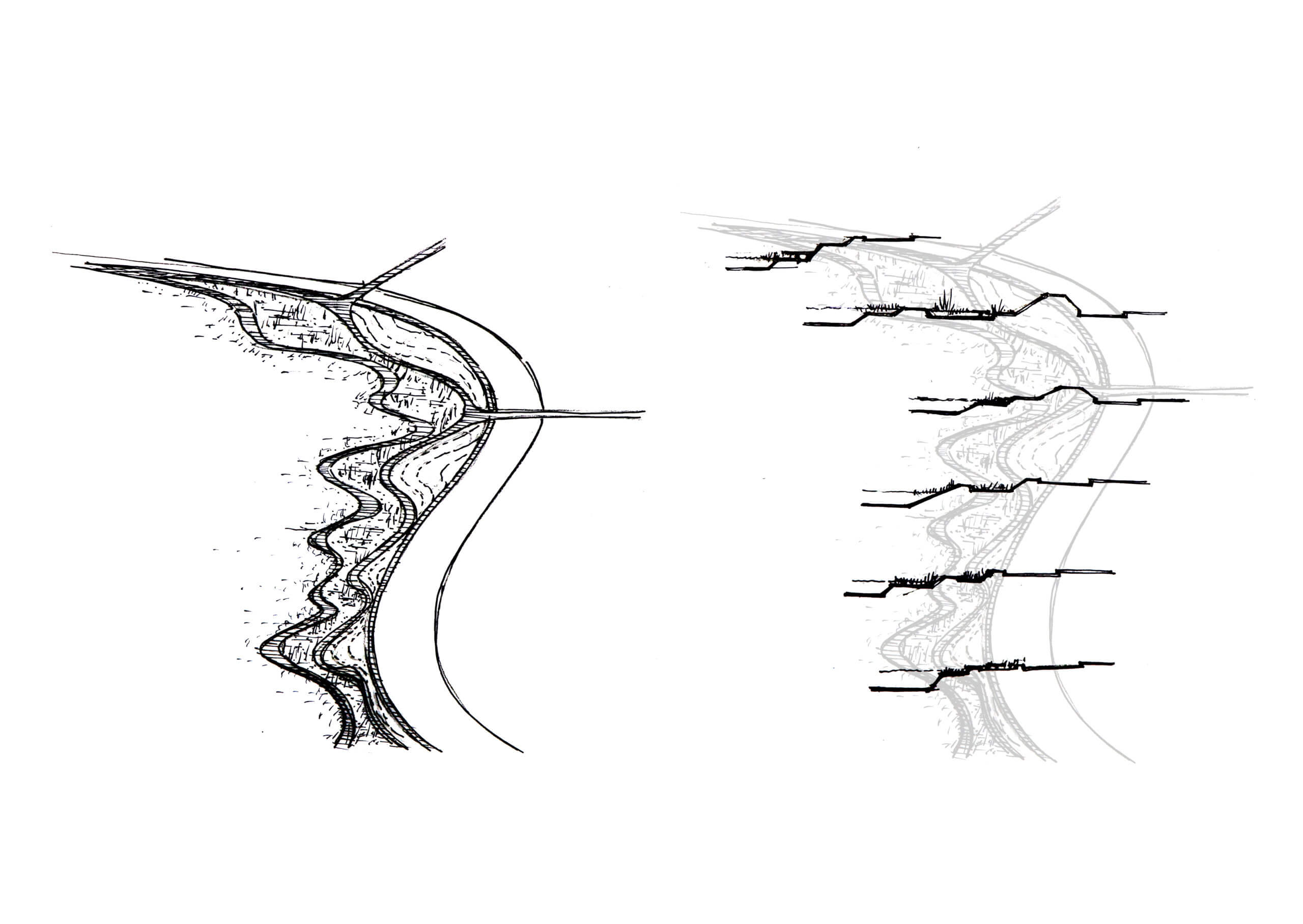

Though this digital emphasis has only become stronger in recent years, particularly in the COVID-19 virtual world, it’s far from the only factor in his design process. One aspect that remains integral is large-format sketching. Sundaram always organizes conversations around shared sketches, whether on a conference room whiteboard or with Miro, an online tool that functions like a virtual sketchbook. The designer’s desk and workspaces are covered in drawings, from quick napkin sketches in pencil to thoughtful graphs and tables translating data quickly from mind to paper. His skill and archived collections help clients build consensus and visualize their aspirations.

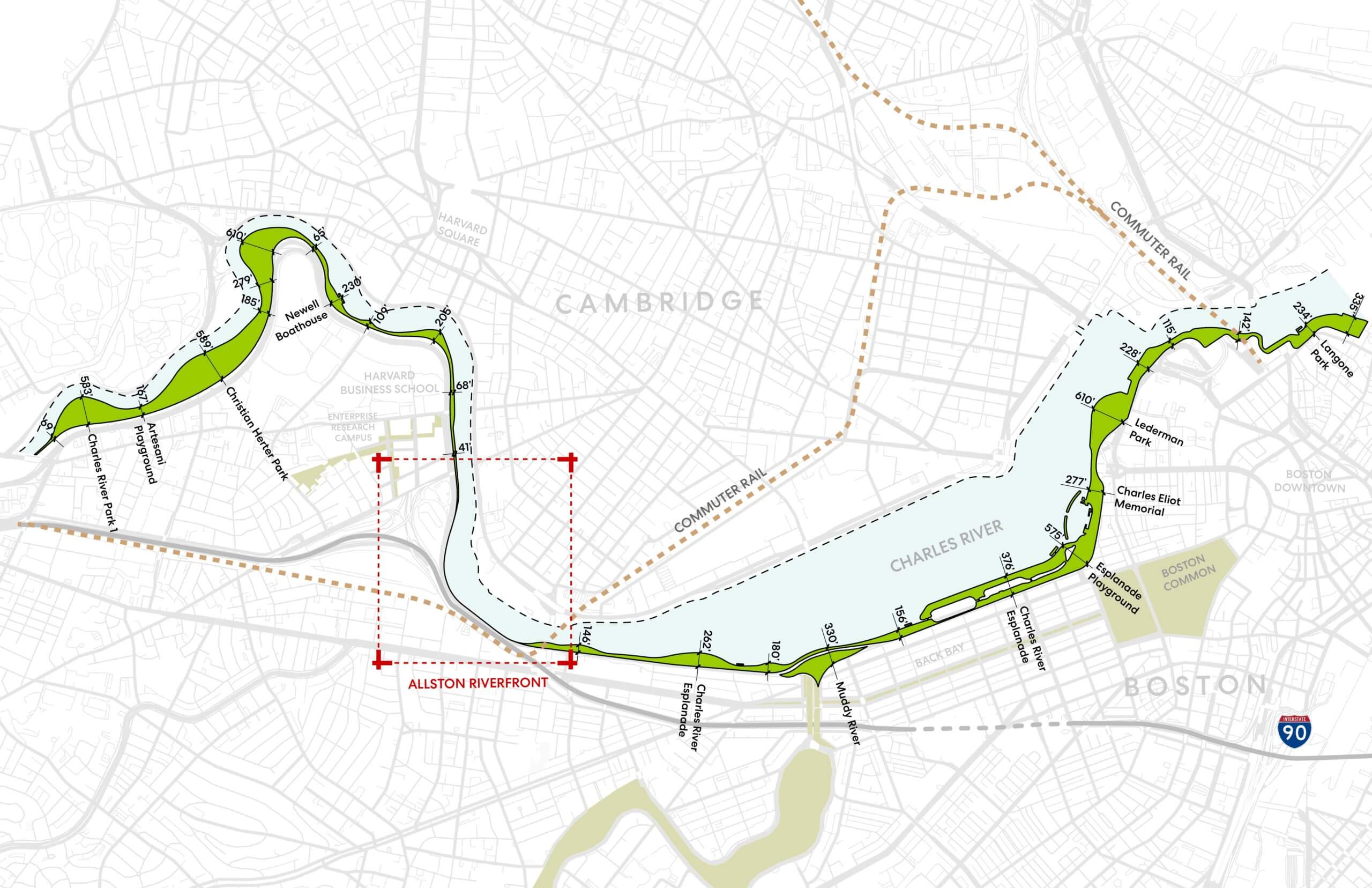

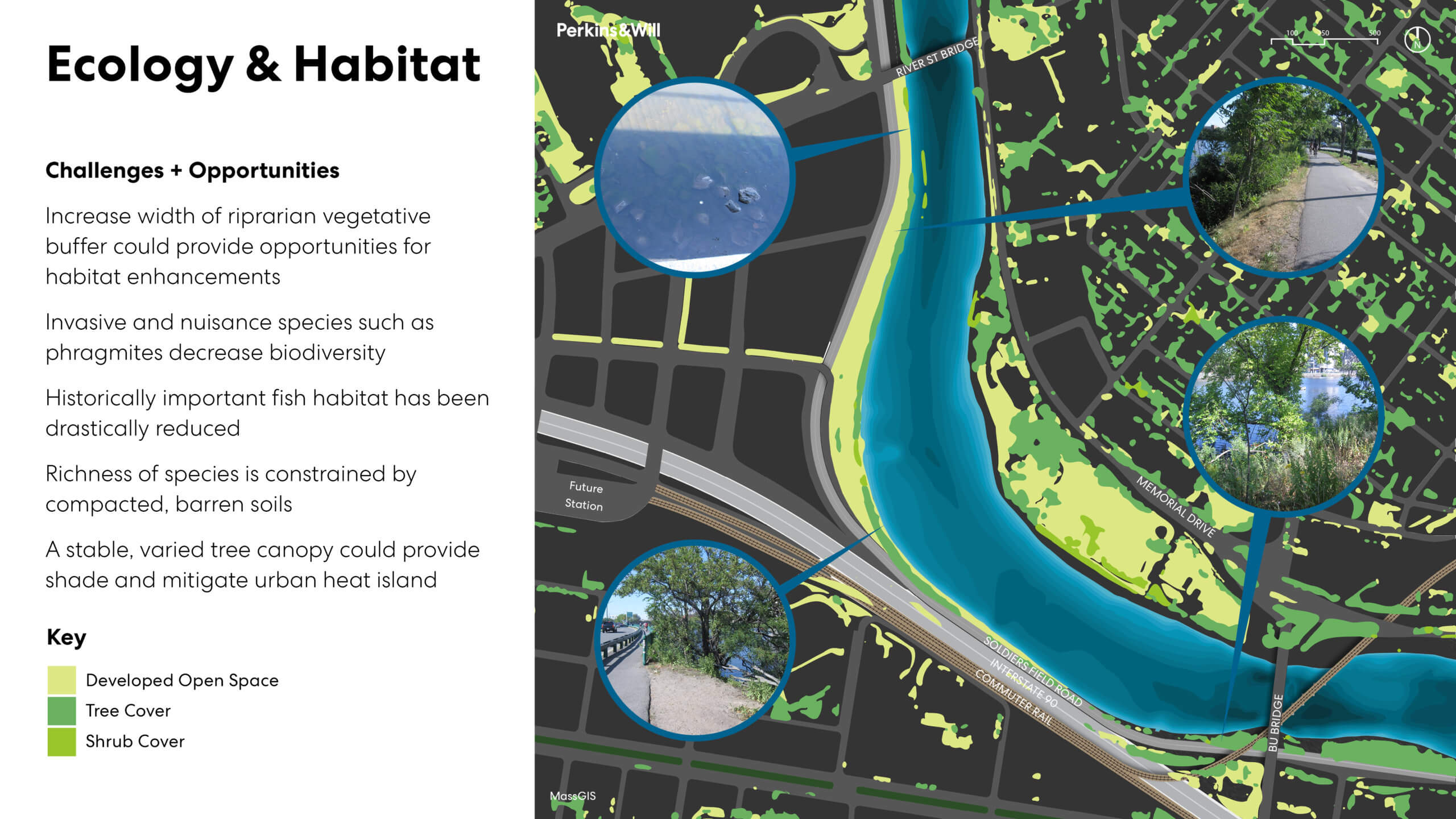

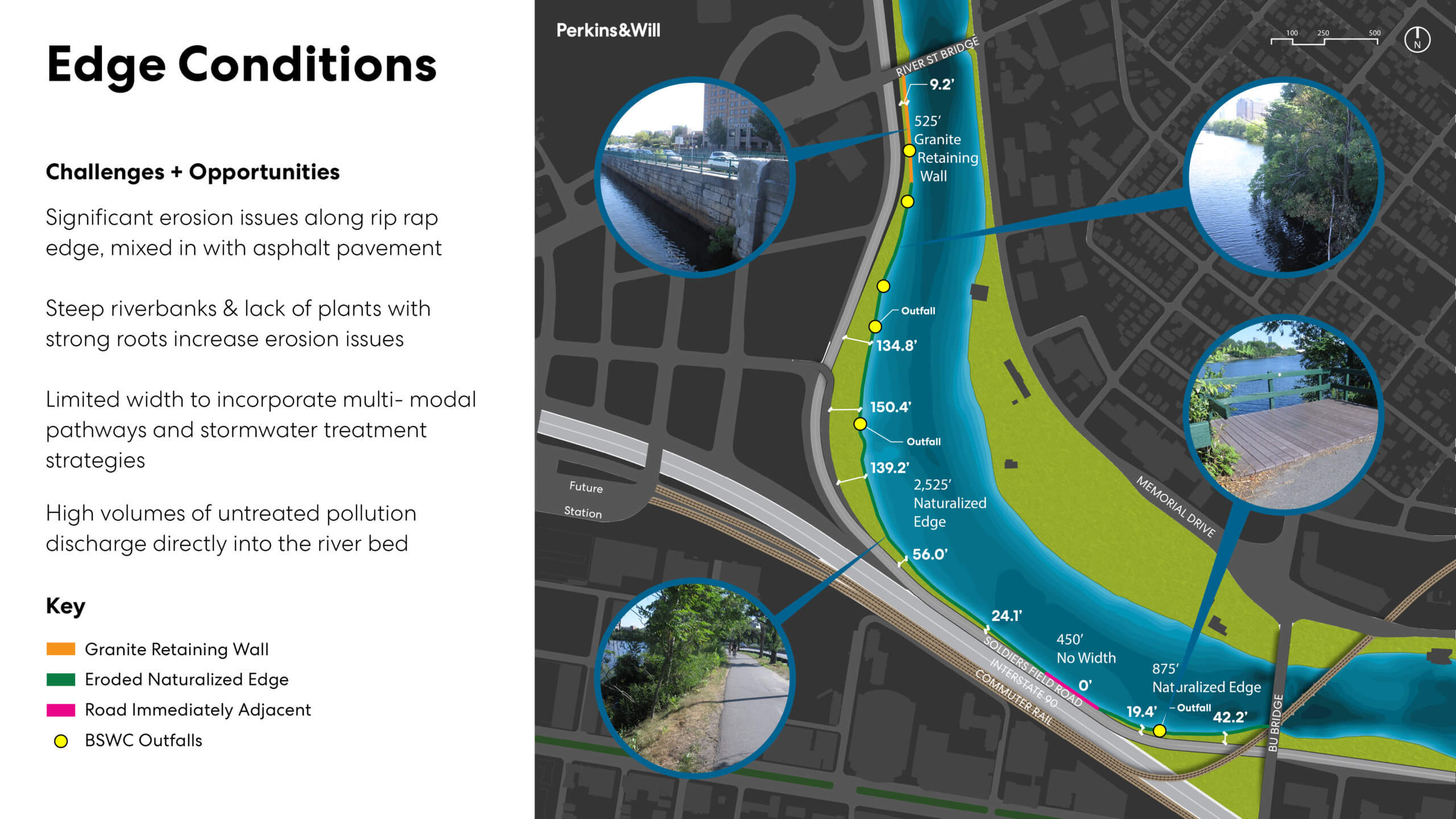

As Sundaram continues to evolve his approach to master-planned stories, he has recently committed more time and imagination toward incorporating research into his practice, too. He is an advisor to the Living Urban Districts (LUD) research team. A Perkins&Will-funded interdisciplinary initiative that brings together a multitude of our laboratories disciplines across studios, LUD explores the intersections of public health, urban design, and mass transit. Sundaram fits into the puzzle by offering expertise in the realm of resilience, notably in a post-COVID world. “I found myself often asking, ‘how can I really make an impact?’” Sundaram welcomes the change of perspective that this research project and partnership has brought to his urban design practice. “Master plans take decades to complete, but the research our team works on every day has the potential to accelerate our mission and bring real change to the communities we work with.”

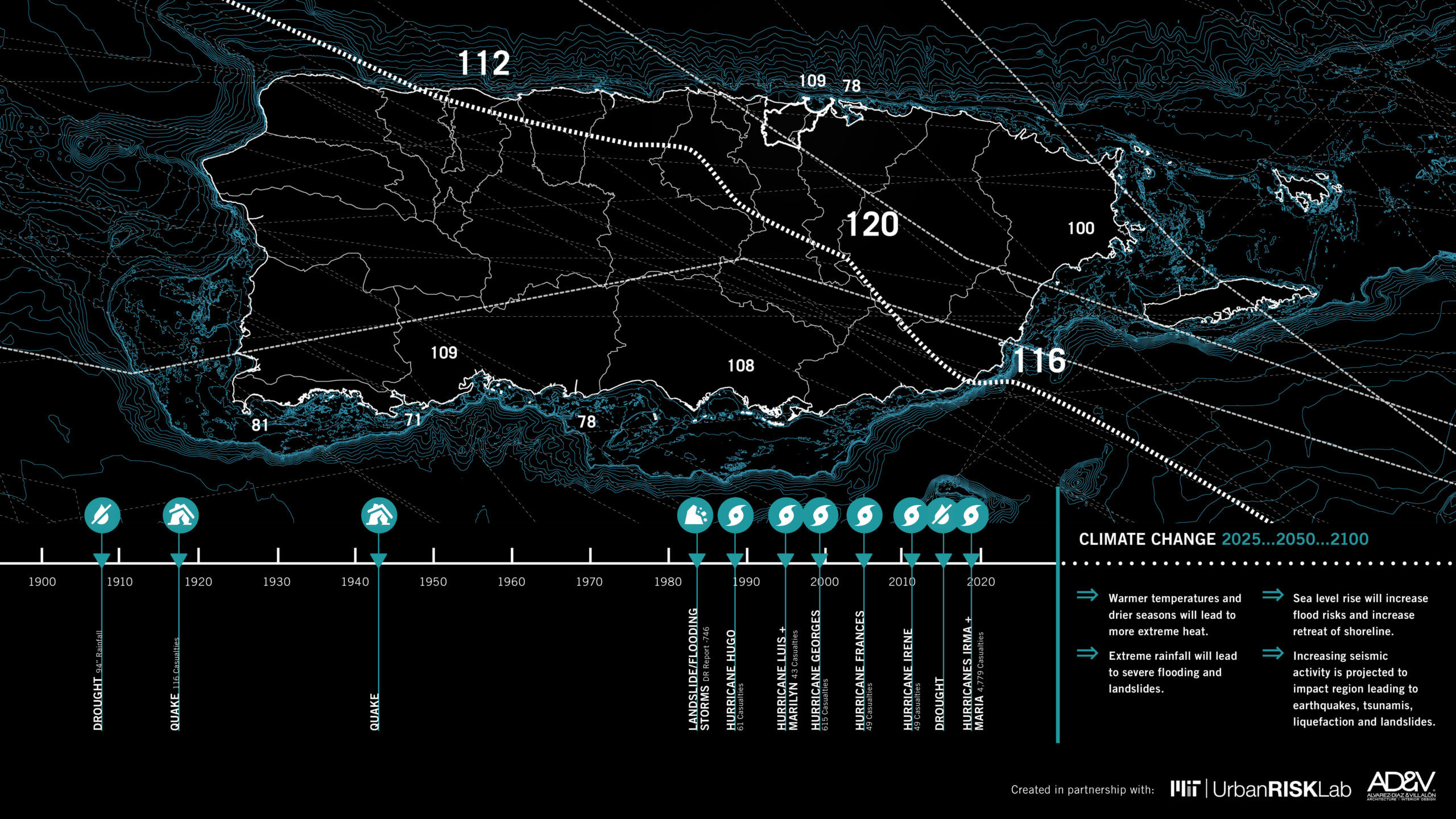

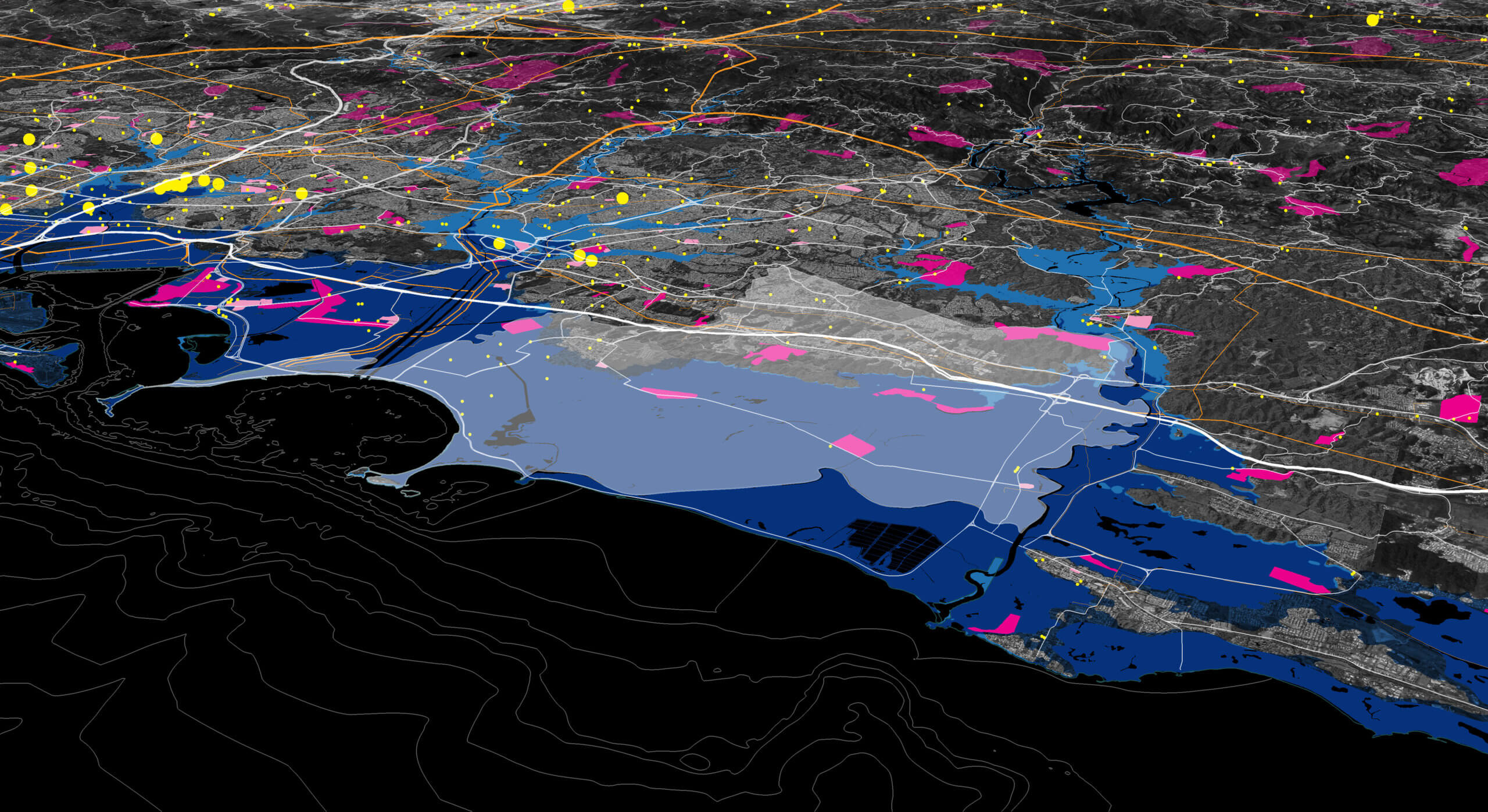

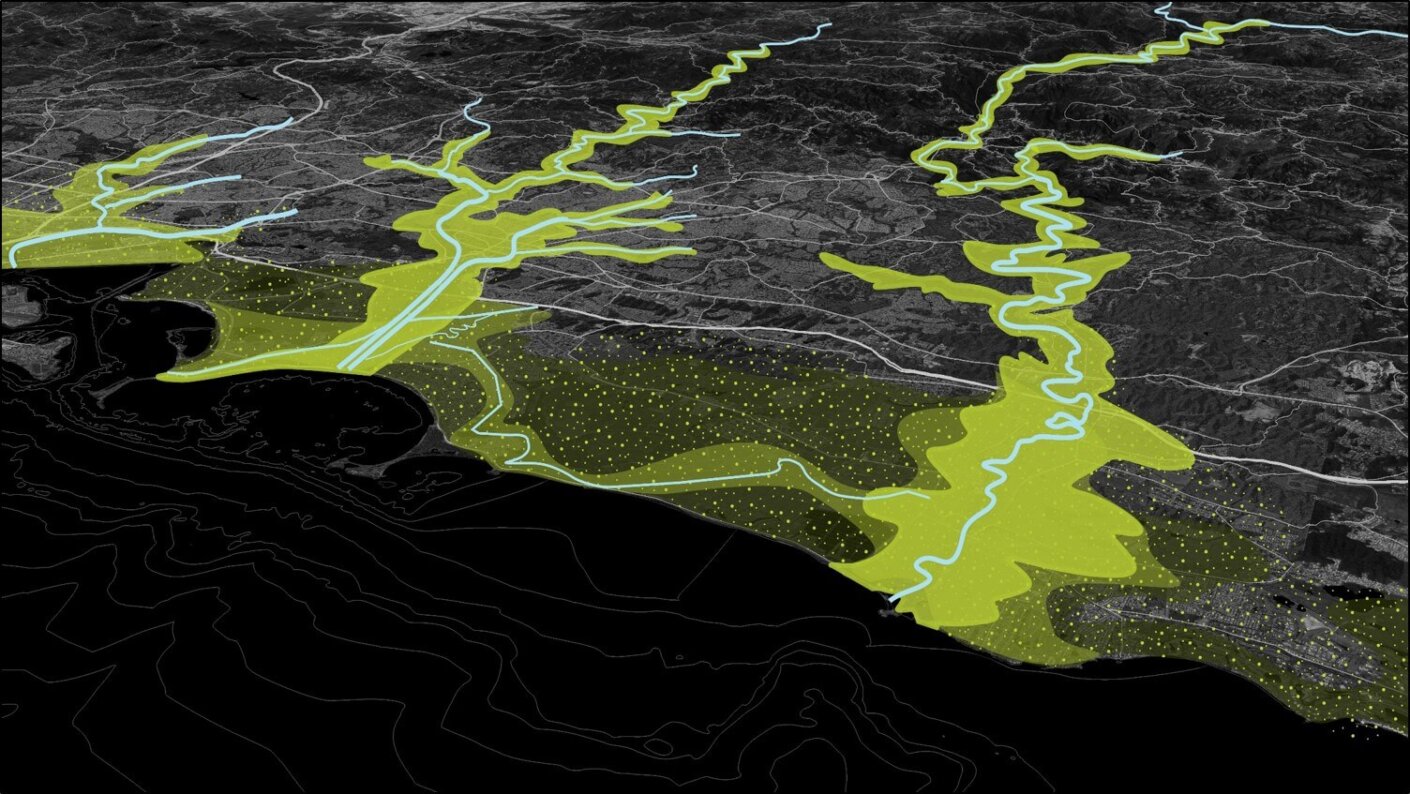

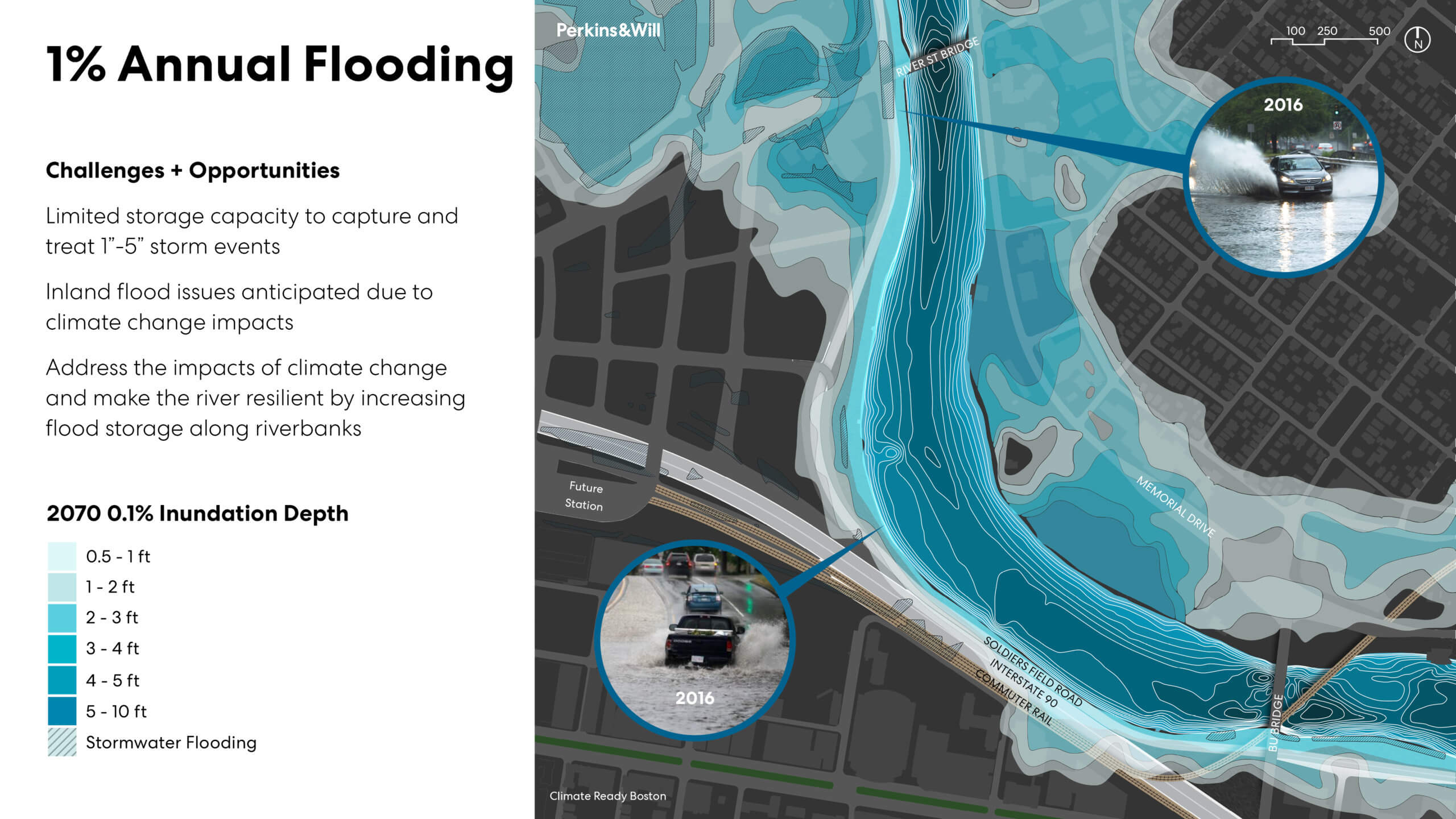

The research efforts thrive within a two-pronged perspective, encompassing technical applications as well as social justice initiatives that dovetail with Perkins&Will’s commitment to justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (J.E.D.I.). Sundaram’s current work is a culmination of his years of refining this perspective, as LUD engages with the multifaceted human issues of climate change.

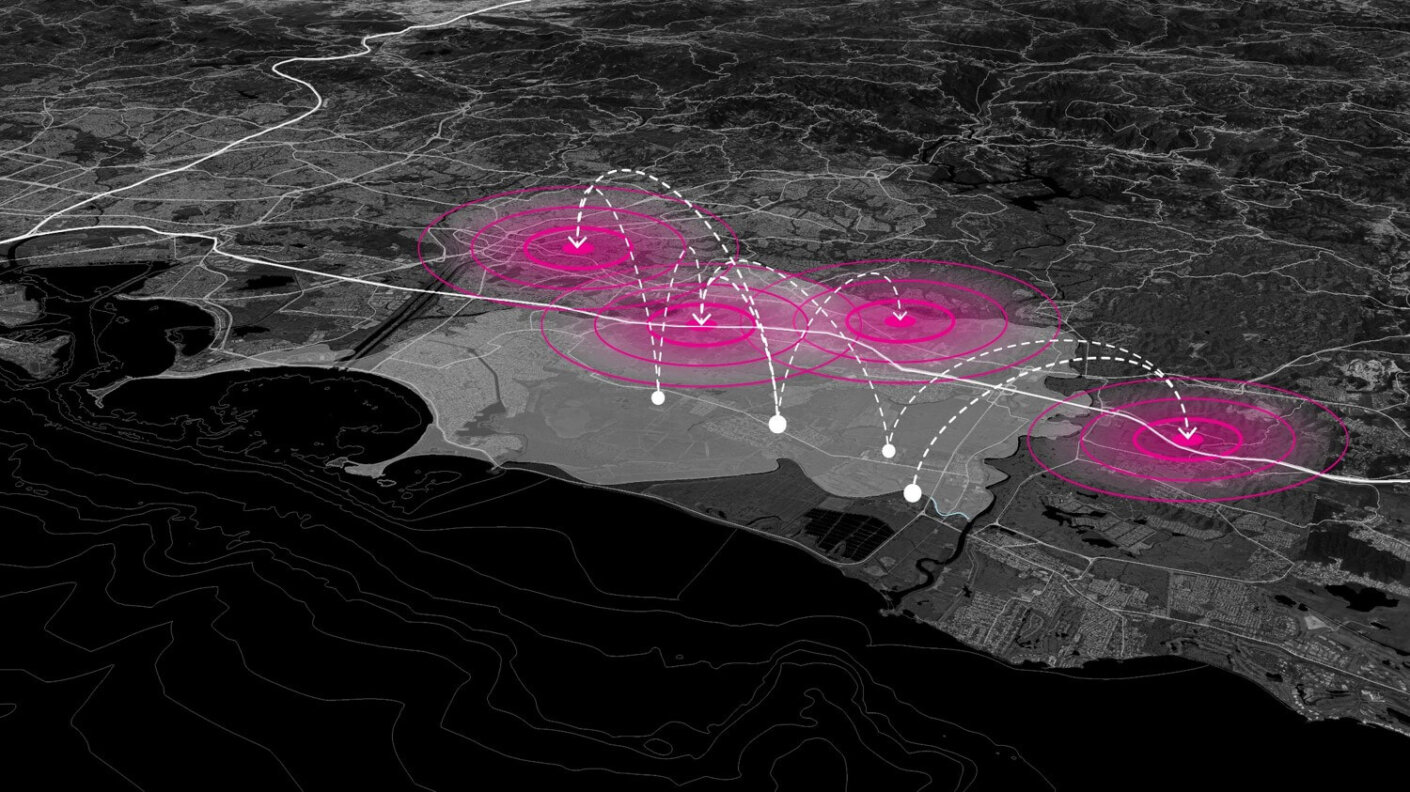

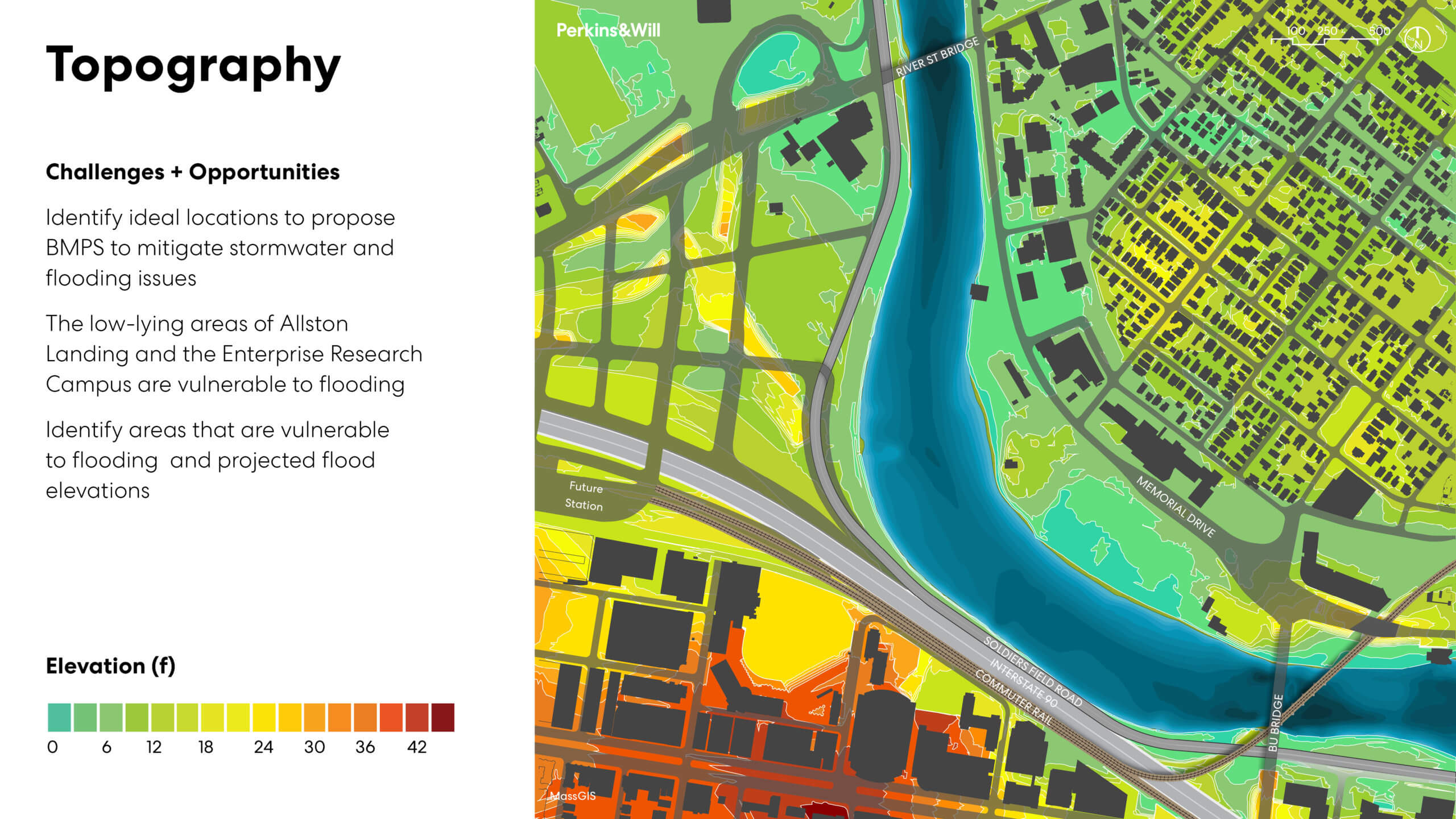

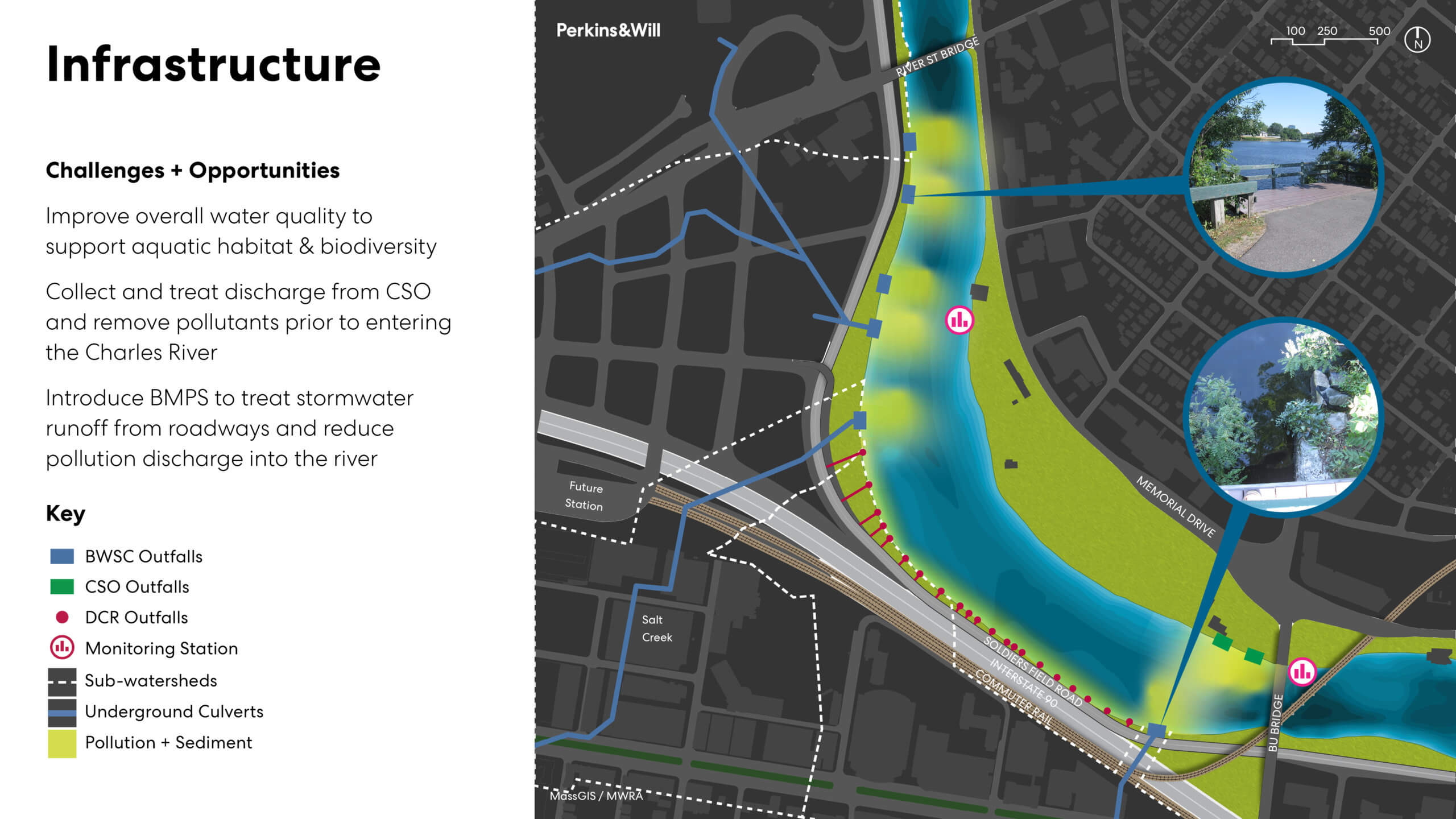

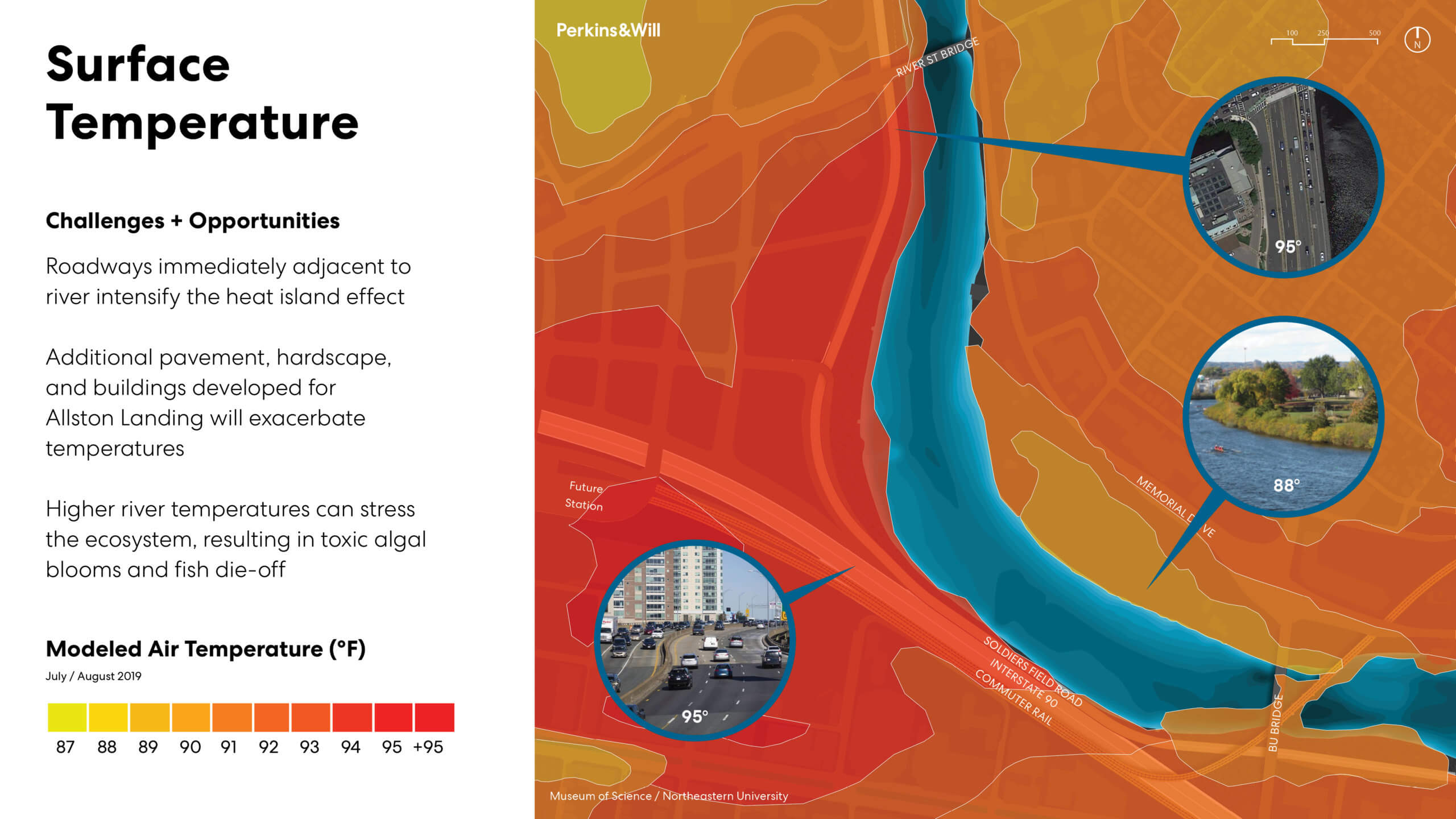

Technically, resilience planning is becoming a pressing need, particularly in coastal cities threatened by rising sea levels. Parallel to these technical needs for housing and urban infrastructure, however, are the social needs. “I see equity through the lens of environmental degradation. If we can use technology to rescue people from the rising tides of climate change, and also use design to elevate the social sphere and access to basic resources, we can begin to solve complex, interconnected issues.”

Sundaram encourages teams, whether master planning a campus or conducting research, to think about the root of the problem, and probe for the simplicity within the complexity. His work sparks real change for communities around the world.