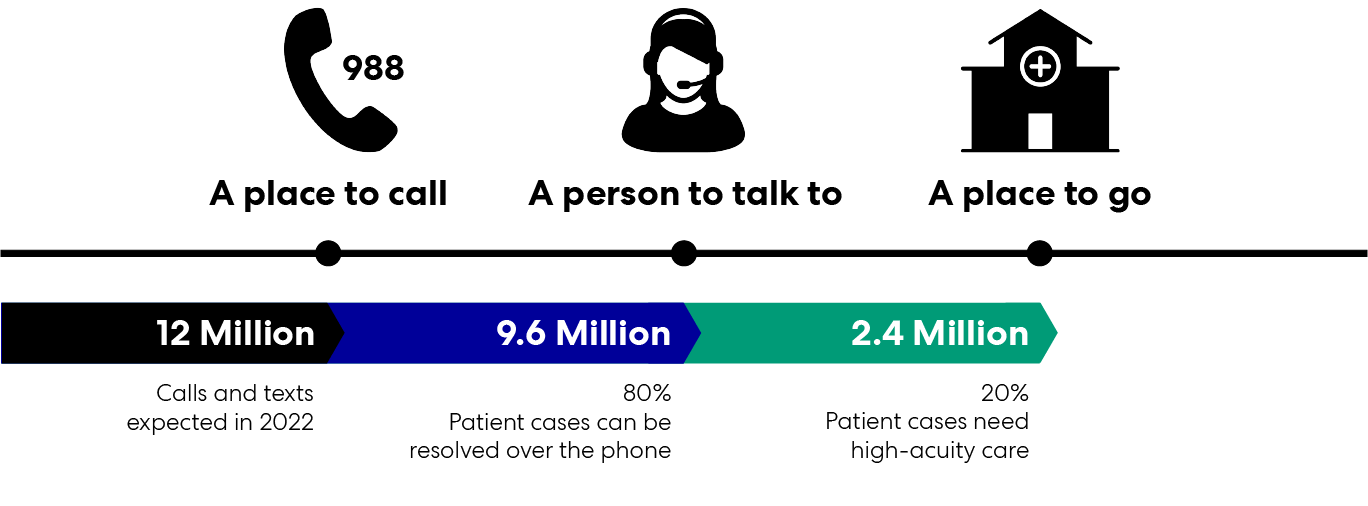

The new hotline is a victory, but the United States needs a thoughtful comprehensive response to behavioral-health and crisis-care infrastructure across the comprehensive care continuum. Technology, process improvement, training, and operational policies are all critical leverage points in the care we provide to people in crisis. Changes to the built environment are a critical leverage point, too.

Perkins&Will has deep expertise working with healthcare clients who integrate behavioral health in their services and have designed for behavioral health at a range of scales. We also partner with our clients to understand their organization and implement process improvement and operational planning. In other words, we design for behavioral health across the whole continuum of care. The spaces at left are a window into what our healthcare future could look like.