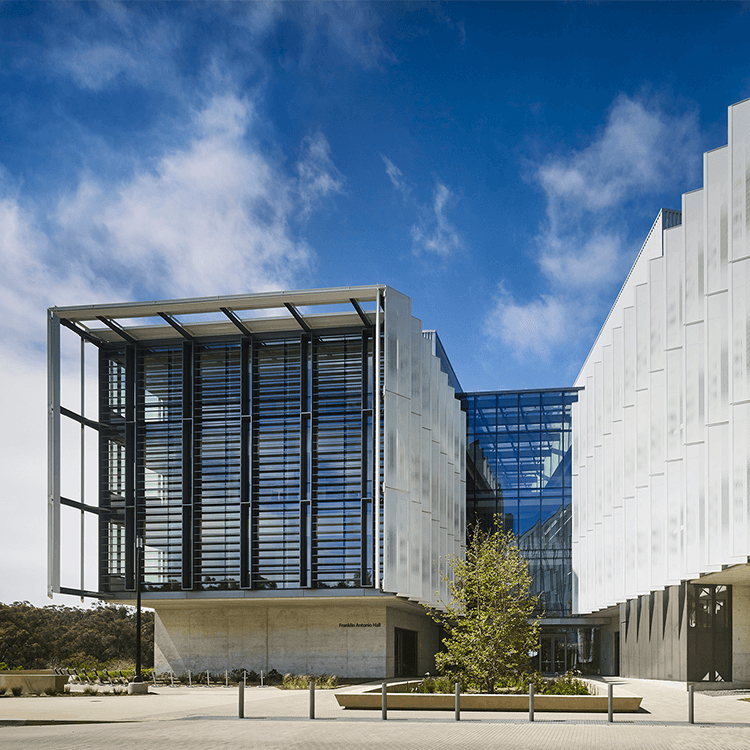

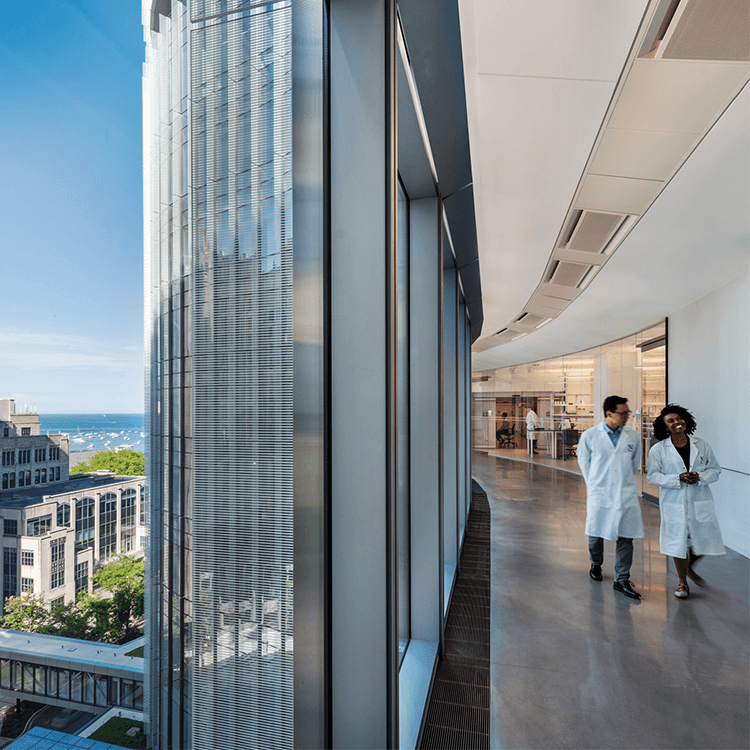

When it came time to expand the campus to advance Fermilab’s research focus on neutrinos—the universe’s most abundant particle, so tiny its mass cannot be weighed—a rigorous yet creative approach was needed. The Integrated Engineering Research Center (IERC) would be the largest purpose-built lab and office building on the campus since Wilson Hall opened in 1974. It was envisioned to bring together, under one roof, different research teams, technicians, and engineers from various disciplines who had previously been scattered across the campus. This would enable collaboration in support of the international DUNE (Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment) project, which aims to unlock the mystery of neutrinos to help us better understand the universe, how it works, and why we are here.

The new IERC had to support ongoing experiments, but it also had to be extremely adaptable and able to accommodate future uses that cannot be anticipated today. Most importantly, it would need to connect to Wilson Hall, further facilitating interaction between the engineering community and researchers. But it had to make its own bold statement without overshadowing the historic structure.