She joined Rhode Island’s “Fix Our Schools Now” coalition and lobbied for legislation to fix decaying school infrastructure. “For a doctoral student, I was pretty active from a policy standpoint,” she says. “I wanted to impact younger students because we can help set their trajectory physiologically, economically, and academically.” Her efforts paid off: In 2018, Rhode Island voters overwhelmingly voted in favor of a $250 million school repair bond.

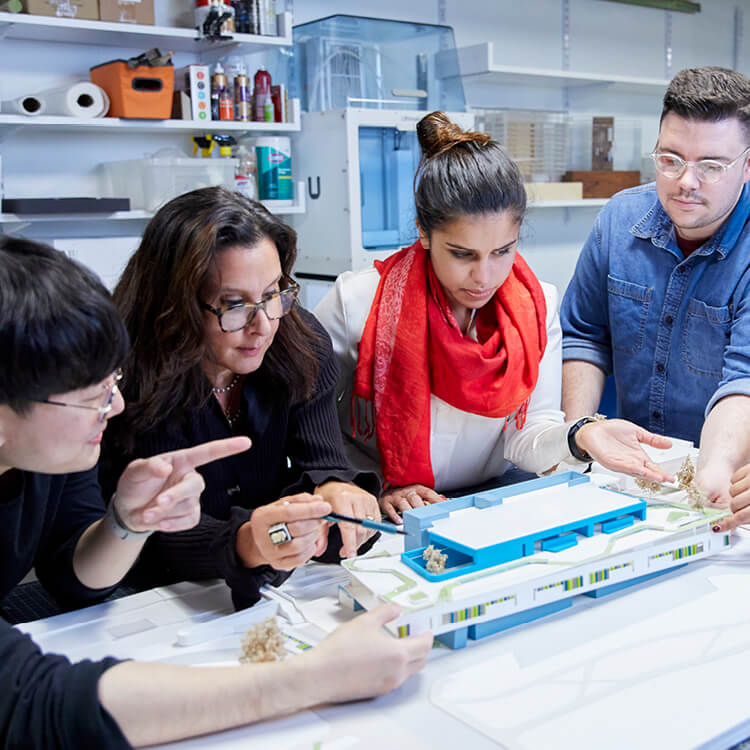

Dr. Eitland joined Perkins&Will two years later as a research analyst, becoming the firm’s first public health scientist. She was promoted to Director of the firm’s Human Experience (Hx) Lab in 2021, which integrates human-centered research into the design process.