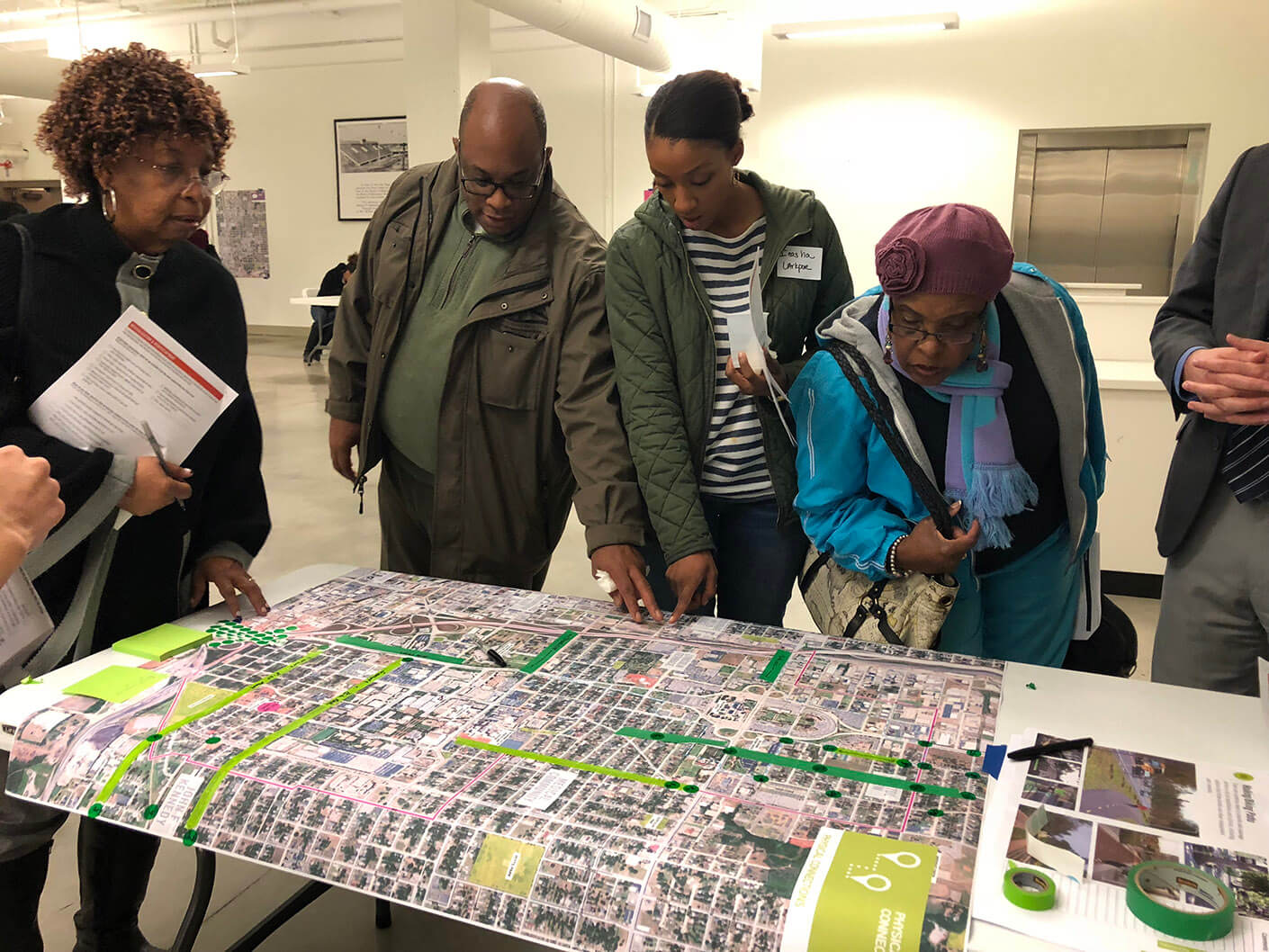

Seeing the success of celebrated research centers like Stanford Research Park in California and Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, many communities have been inspired to create their own. The basic idea—co-locating technology and creative startups with an academic research center for the benefit of both—has since matured into a strategic blend of higher education, economic development, and placemaking. “Innovation districts are a regional sandbox for everyone to play in,” says Mark Romney, former chief industry alliance officer for Aggie Square, a 24-acre innovation district on the University of California, Davis campus in Sacramento. “Academia, industry, and the community can all come together.”

What the next generation of innovation districts is all about