The cabin belonged to Bichelmeyer’s great-grandparents, and her father was born there. Bichelmeyer enrolled at KU as the youngest of 10 children and a first-generation college student, and she went on to earn four degrees, culminating in a doctorate in educational communications and technology. After working at other universities for two decades, she returned to her alma mater in 2020 to serve as provost and executive vice chancellor.

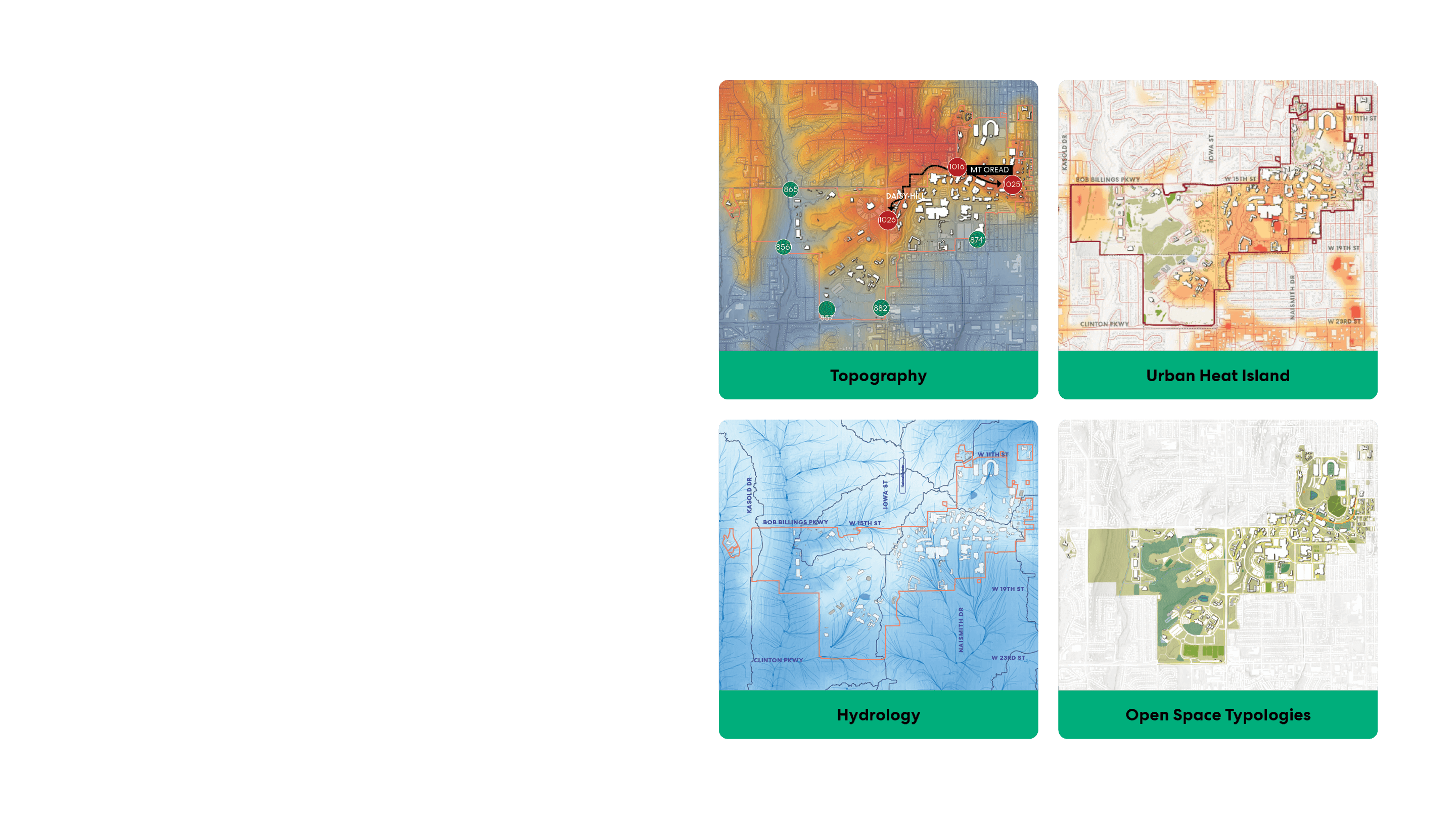

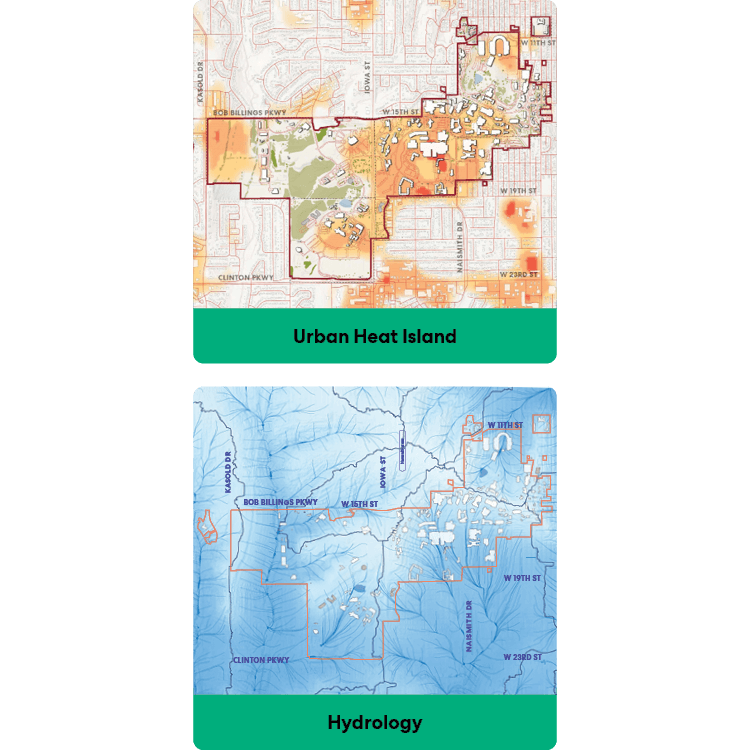

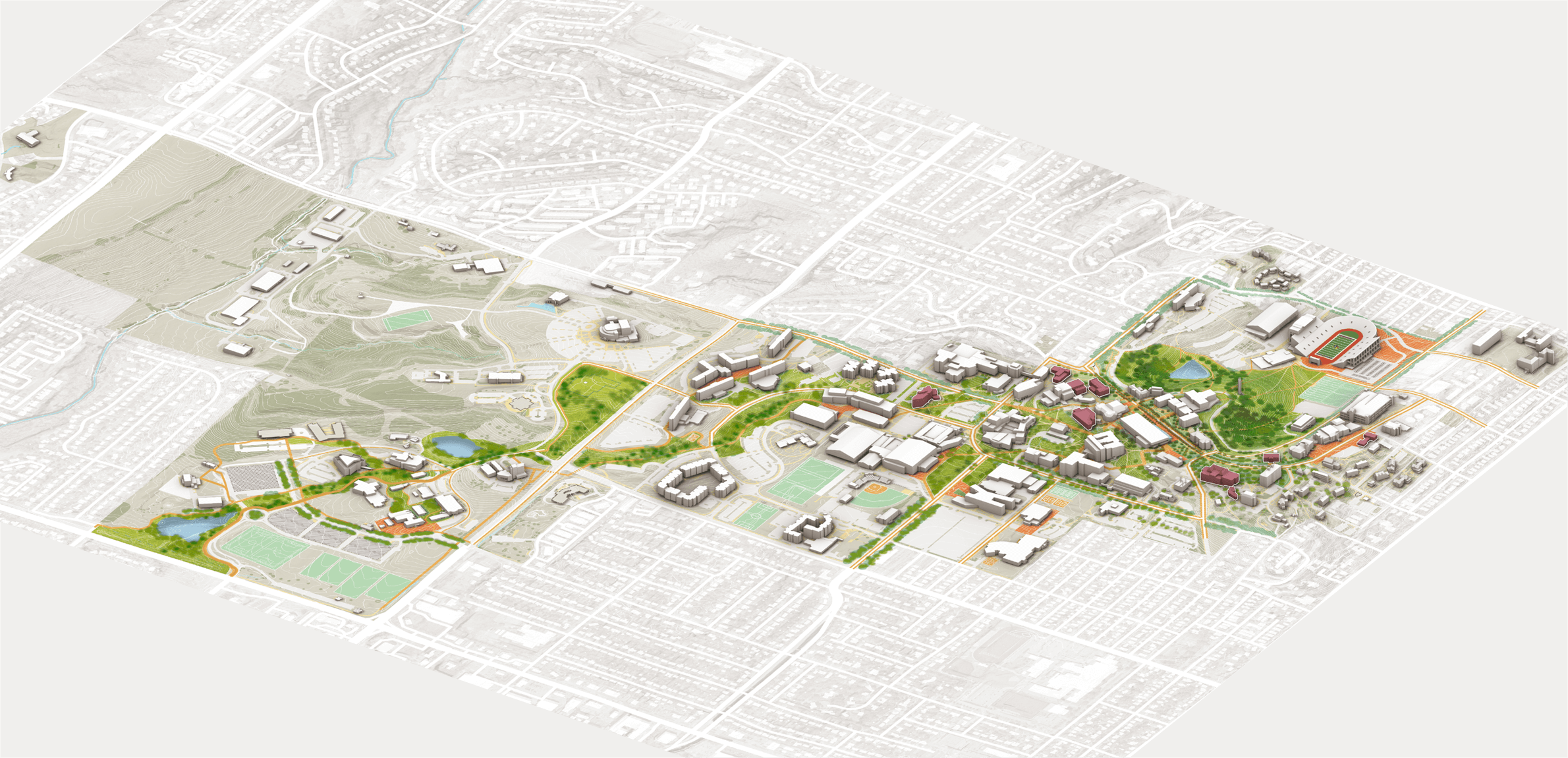

Bichelmeyer sees her journey from humble beginnings to the provost’s office at a major research institution as a testament to the promise of public universities, and she wants to preserve that promise for future generations. She displays the sketch not so much as a family memento, but more as a reminder that KU is a relatively recent, and potentially fleeting, presence on the hill. “This campus wasn’t here 160 years ago,” she says. “In another 160 years, we don’t want Mount Oread to go back to being empty. We need to serve as stewards. Our job is to keep the campus moving.”

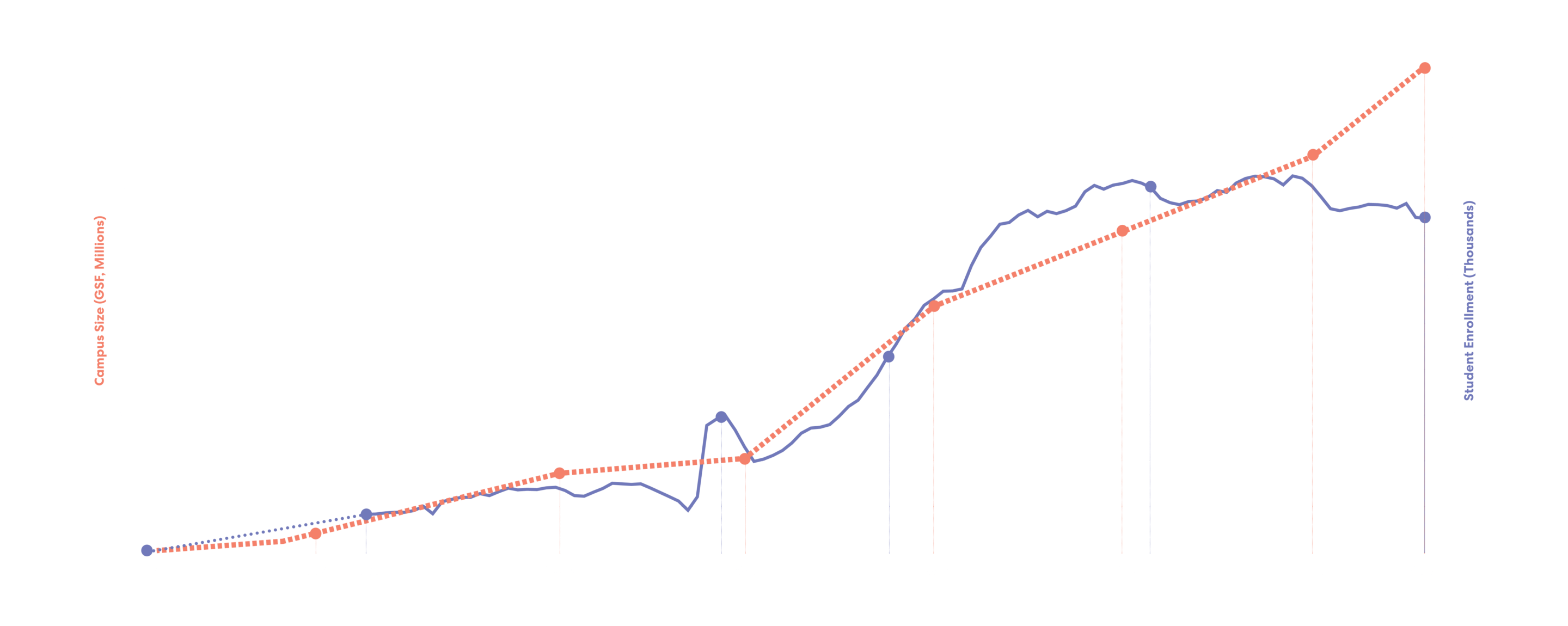

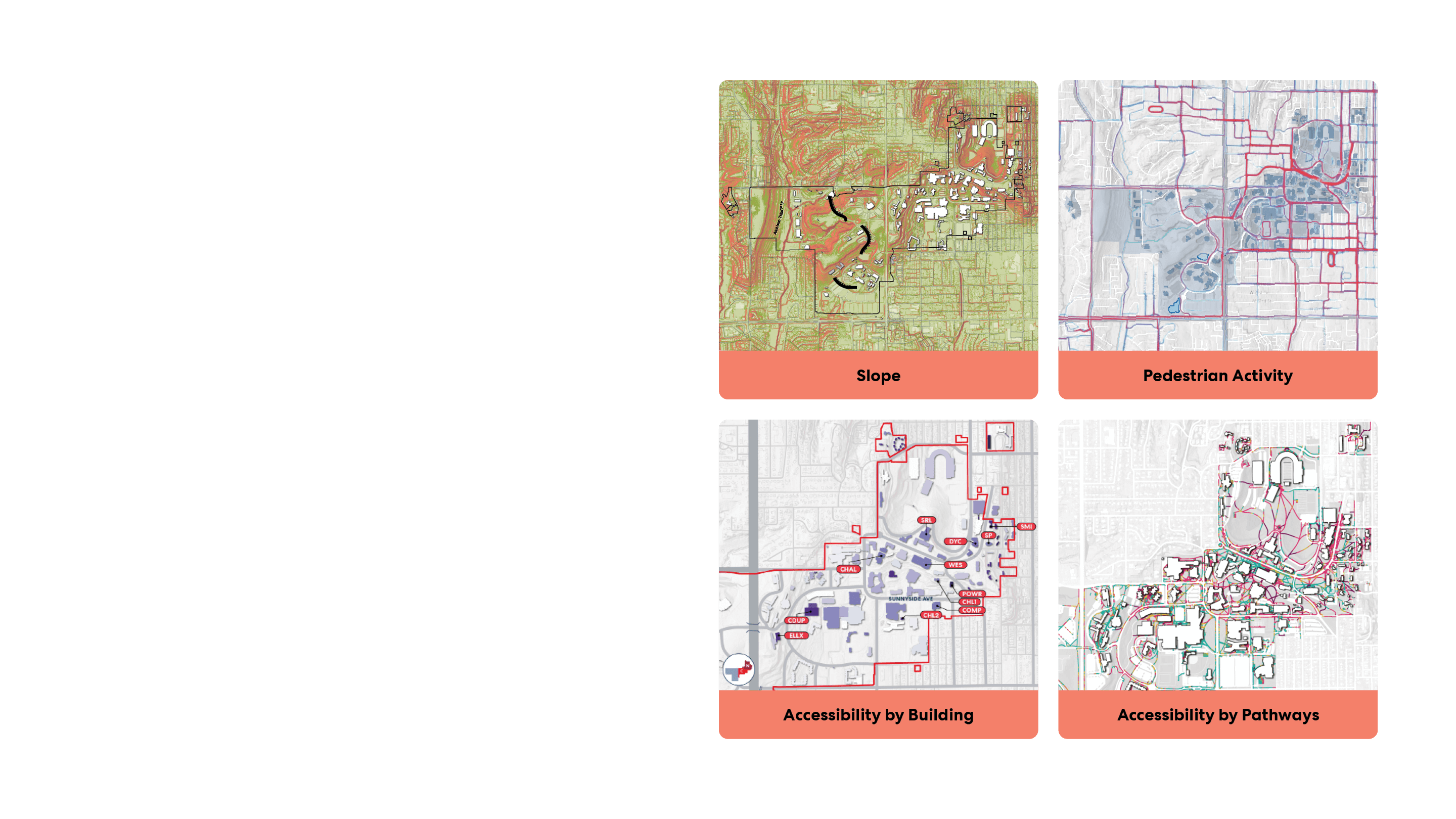

Note that she didn’t say her job is to keep the campus growing. KU expanded for decades to meet a seemingly endless demand for more classrooms, office space, and research facilities. The university’s previous master plan, completed in 2014, called for 40 major building projects totaling more than $700 million. But soon after Bichelmeyer returned to campus, she and her teams discovered a $50 million structural deficit, a deferred maintenance burden totaling more than $750 million, and about 900,000 square feet of excess square footage. And like many U.S. universities, KU is confronting a demographic cliff, financial challenges, hybrid learning, and the uncertainties of climate change.