Taylor: Sacramento is fortunate to be the capital city of a very progressive state. California Governor Gavin Newsom inserted billions into the budget for a major passenger rail program in an effort to phase out fossil fuel-based vehicles. By 2024, we’ll have two additional heavy rail stops in the city in addition to our main station. We also have state funding to organize regional commuter bus routes through the central employment areas of the city that will connect to rail stations for transit to the Bay Area and Central Valley.

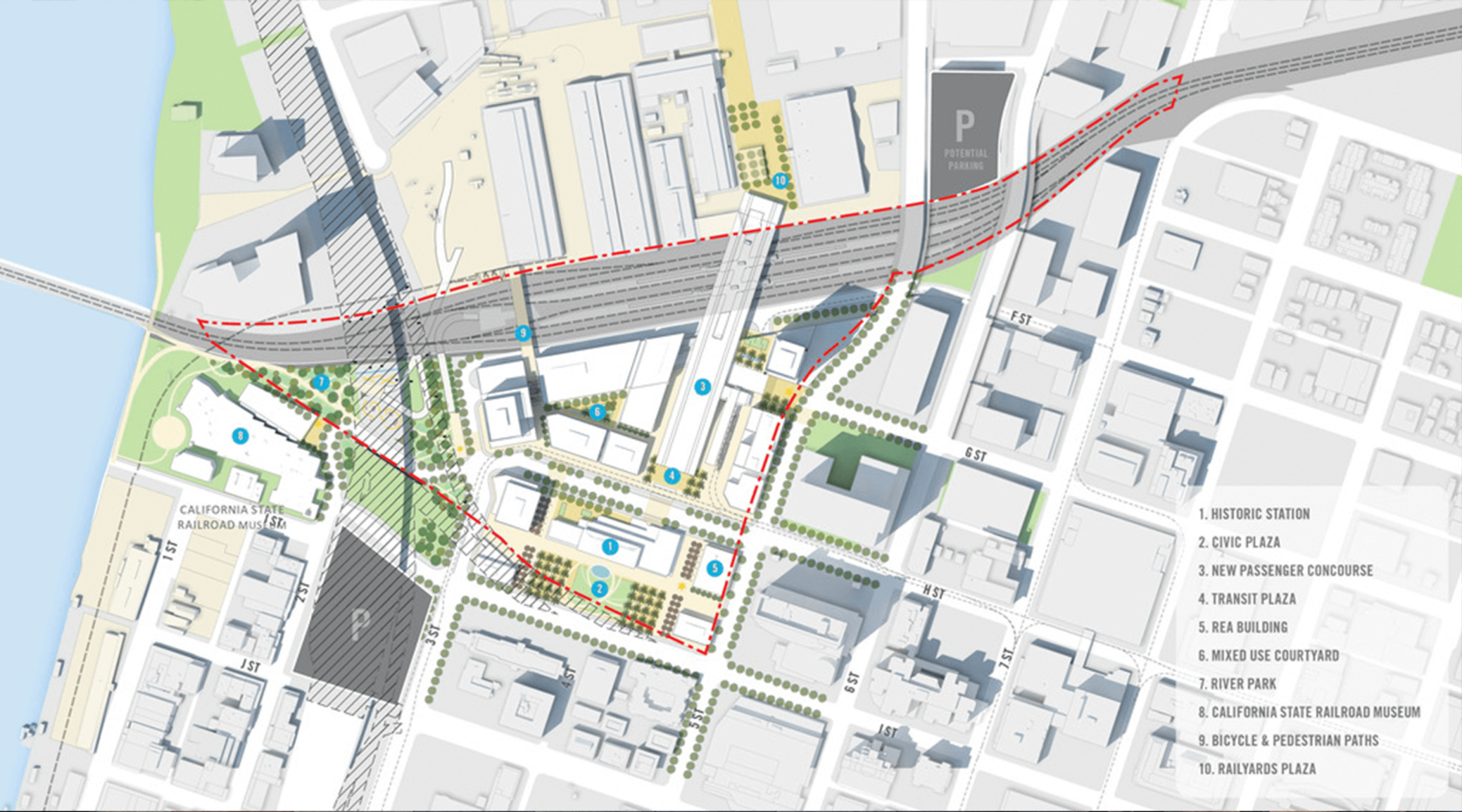

The master plan for Sacramento Valley Station features a district energy strategy that is zero carbon and net positive on both energy and water usage. A 75,000-square-foot bus station slab with concrete pilings will absorb the heat energy from the soil to create a ground source heat pump that will aid in heating and cooling the buildings on site. We’re also building a five-block bicycle track that will run perpendicular to a few of the city’s major bike routes, drawing cyclists into the station.

Tierney: Montréal, in Québec, Canada, just developed a new light rail system, Réseau Express Métropolitain, that, though it appears conventional on paper, is designed to amplify the 15-minute radius for the folks living near the new stations. In the end, the hope is that they will become a catalyst for higher density in the areas around those stations.

Wieland: Austin, Texas recently implemented a program with a significant budget that is going to emphasize bus and rail, marking a massive shift away from cars. The program also works to prevent the unintended consequences that such transportation investments can often have on equity, such as displacing people.

Also, Washington, D.C. introduced the 15th Street bike lane–a two-way protected cycle track that goes right in front of the White House. It’s such an important pathway for the city’s commuters, and it’s so well-used. If you can put a protected bike lane in front of the White House, you can do it anywhere.