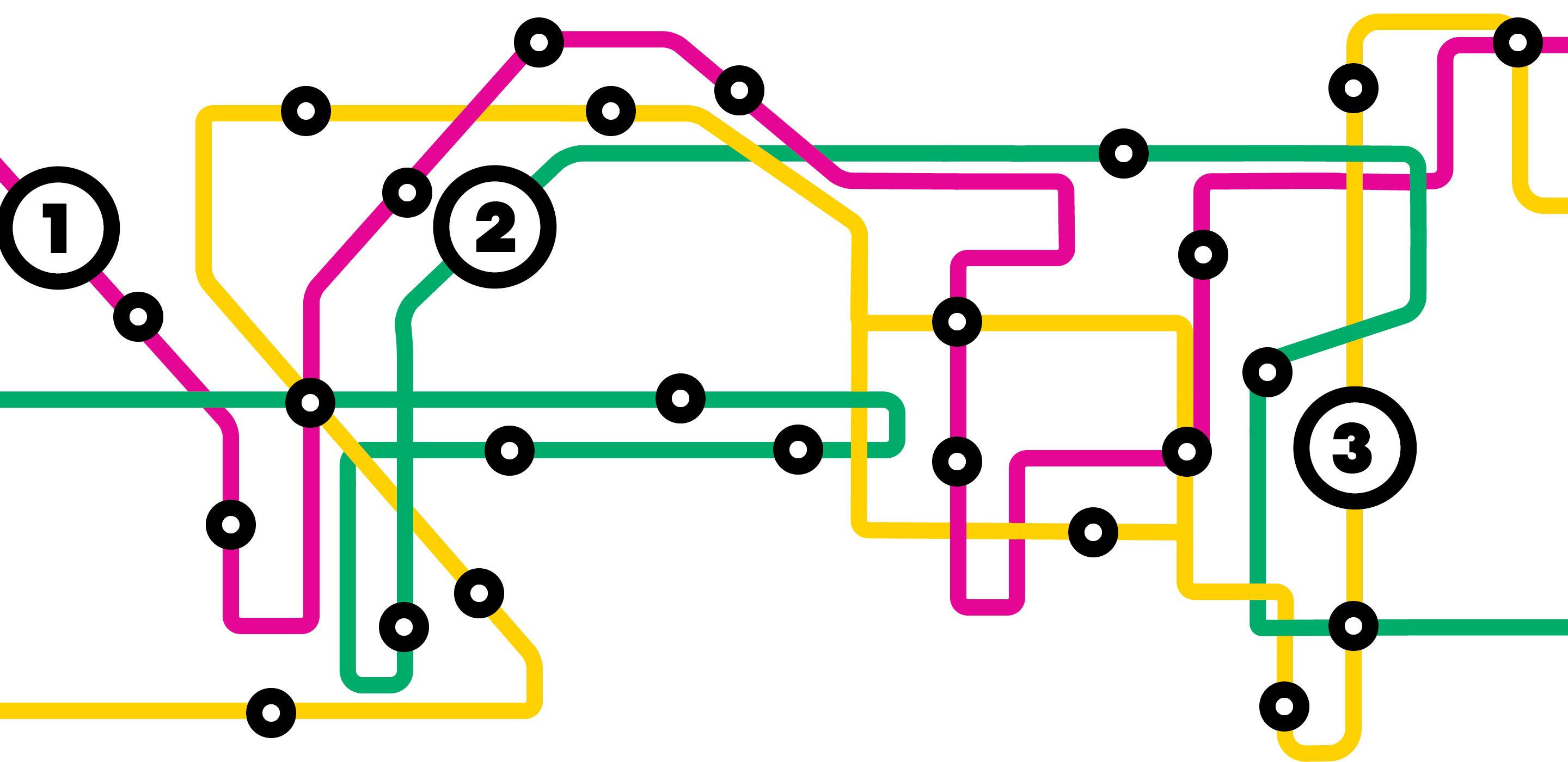

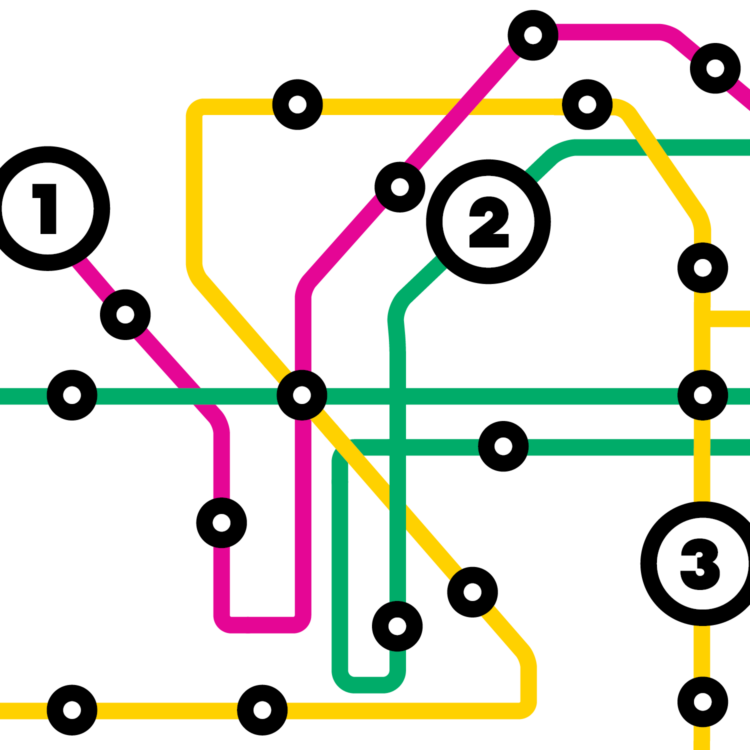

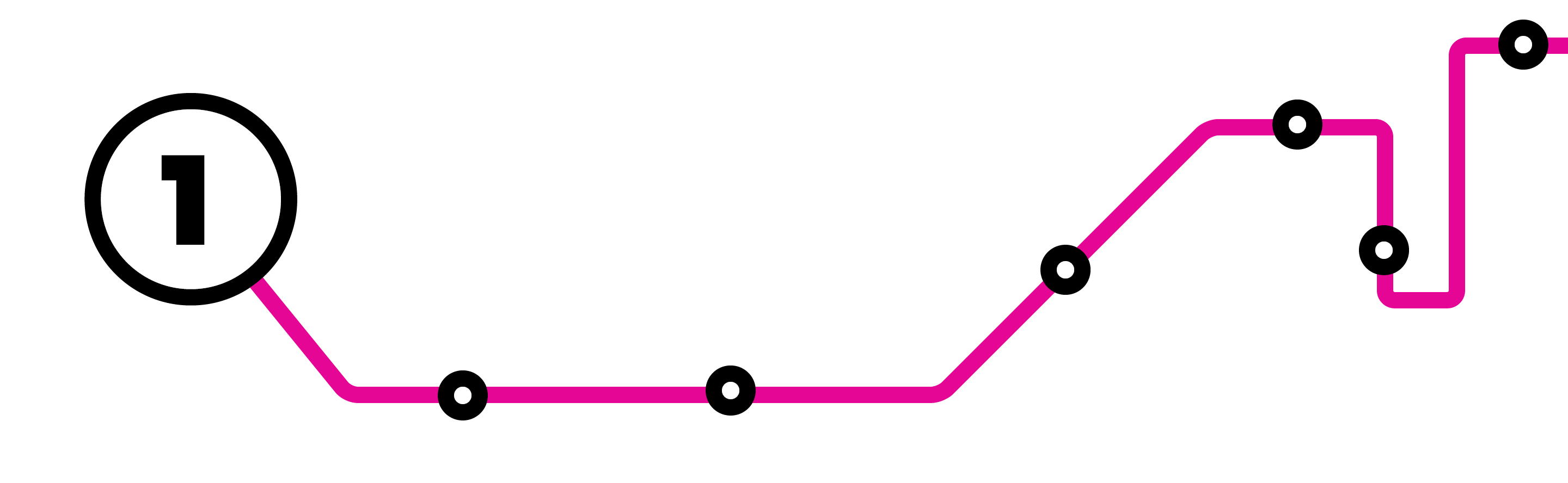

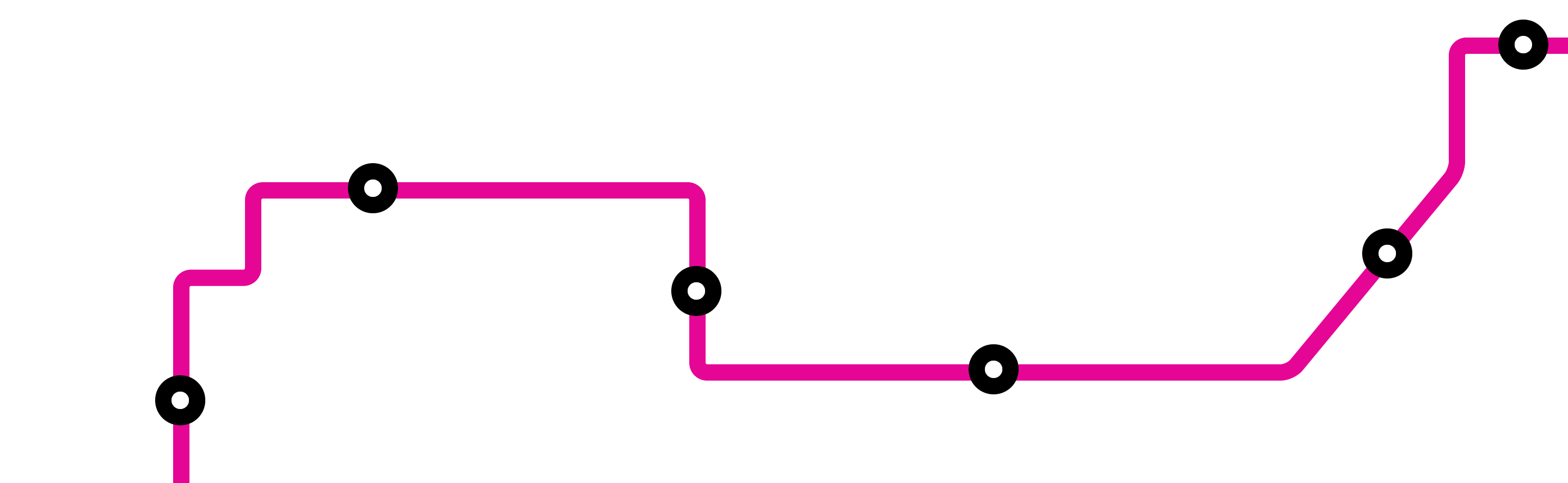

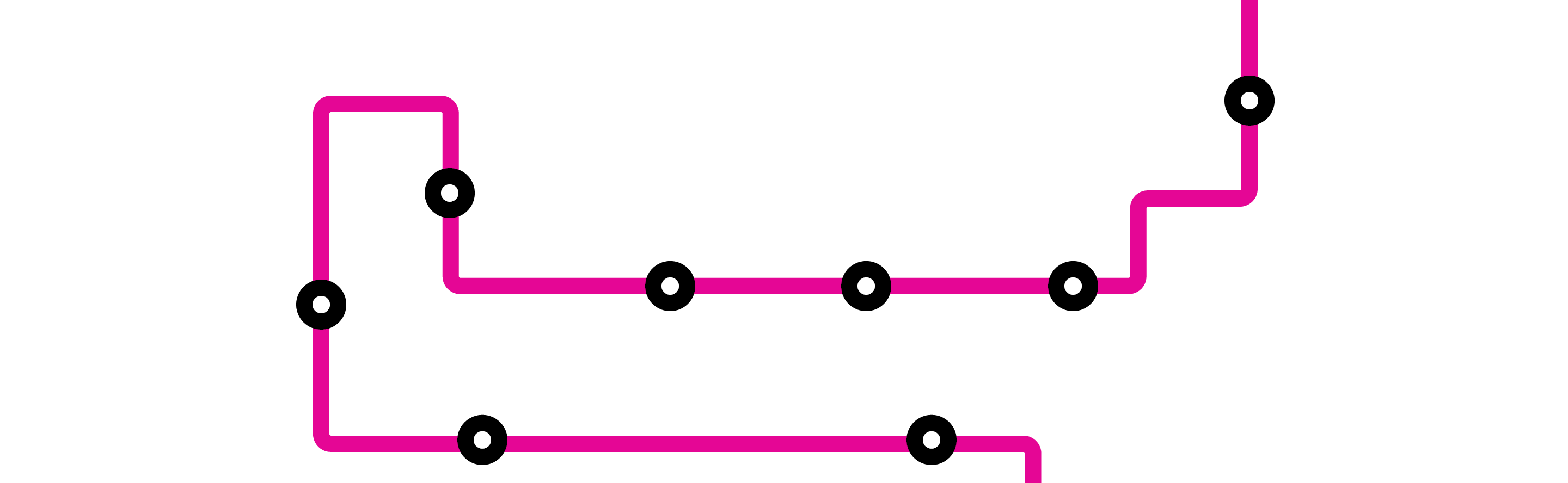

Infamous for its maze of chronically overloaded freeways, the city of Los Angeles has been making real strides in building out its light rail network over the last decade. One key leg is the $2.1 billion, 8.5-mile Crenshaw-LAX connector, which will finally provide a critical north-south connection to one of the world’s busiest airports. However, the line also slices through the loci of several historically Black neighborhoods. It will run at-grade for 1.3 miles down Crenshaw Boulevard, which has been referred to as “the cultural and commercial spine of Black L.A.”

Ever since plans for the transit project were announced over a decade ago, South L.A. residents have been concerned about the disruption of this physical and visual barrier and its potential to negatively impact local businesses, discourage pedestrians, and divide the community. “Infrastructure projects are initiated at the highest level of privilege, and typically communities of color don’t have the opportunity to make decisions about their future,” says Jason Foster, president and COO of Destination Crenshaw, the nonprofit that’s in charge of a community-led solution.