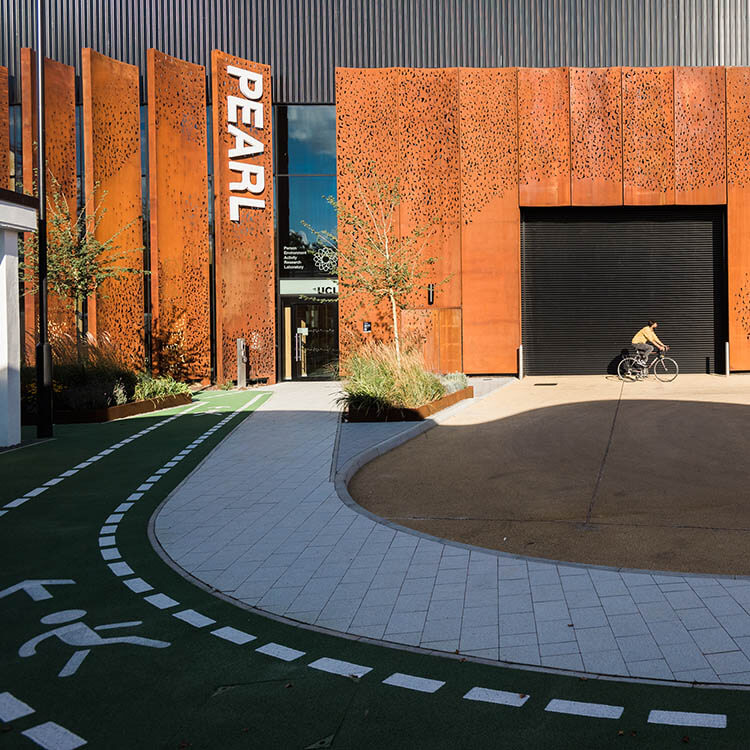

By providing a true-to-life lab where researchers can control variables and directly observe participants, PEARL helps researchers collect comprehensive and accurate data to inform urban planning and design.

Before PEARL, researchers typically relied on computer surveys or in-office interviews to try to understand how, for instance, the loud sirens of a passing ambulance might affect autistic children at a public park. Although these studies are informative, the results are skewed by respondents’ perceptions and biases. At the same time, controlling all the variables in an outdoor urban space is not feasible and the costs of conducting on-location research can be prohibitive.

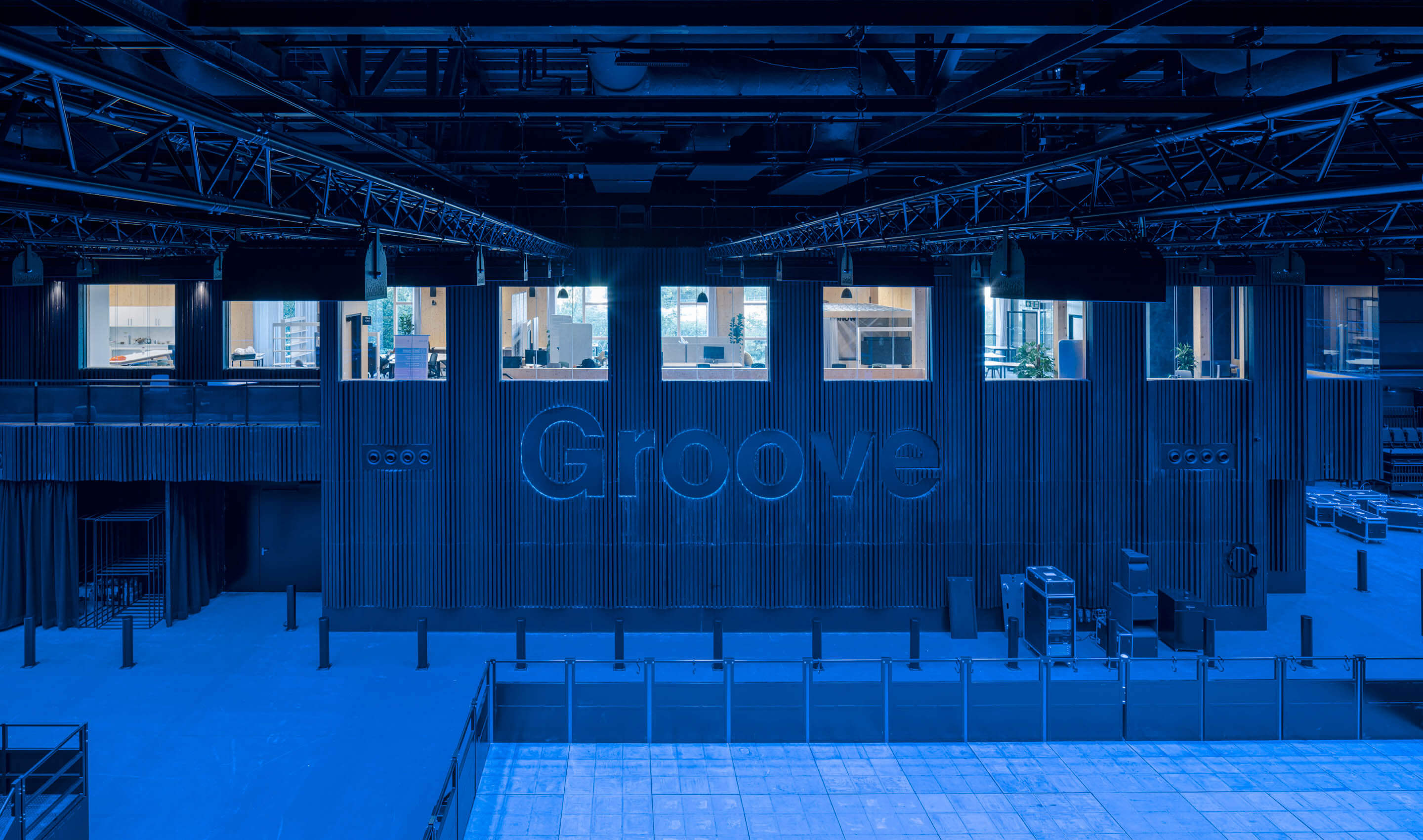

PEARL, on the other hand, provides a realistic environment that is completely controlled. For example, in one recent series of experiments, researchers created a park setting that included a living tree, artificial plants and grass, and real leaves on the ground. The 30-by-30-foot scene blended seamlessly into middle-distance video footage of a London park projected on four large screens surrounding the space. Researchers then invited children with cognitive challenges into the area and recorded their reactions to street noise and other sounds. The goal is to inspire park planners to create acoustically protected spaces for children who have difficulties discerning sounds in nature from urban noise.

PEARL also improves mobility by allowing researchers to study how people of all abilities experience spaces like train stations and airports. Recreating rail platforms, bus stops, jetways, and other transit hubs helps ensure that everyone can use public modes of transportation safely and comfortably.

But researchers ask questions about more than just physical access, Tyler says. With the ability to fit study participants with brain scanners and other sophisticated equipment, PEARL researchers can record how participants’ brains and bodies react to stimuli in public spaces, gaining insights into their perceptions and feelings.