From hospitality to healthcare, wellness has become a global obsession in recent years, igniting a movement toward healthier lifestyles that now touches nearly every sector and demographic. It’s almost impossible to escape the digital onslaught of influencers touting the next fitness fad or miracle supplement—and for good reason. The global wellness economy reached 6.3 trillion dollars in 2023 and projections continue to grow. Yet mental health spending made up only 3% of that total.

As humans collectively strive for healthier bodies and longer lives, mental challenges still arise. One in five adults experiences a mental health disorder each year, and cognitive decline is the leading cause of disability among older adults. With all this focus on optimizing physical fitness, are we remembering to check in with our brains?

Brain health is increasingly viewed as a key component of “brain capital,” a framework that recognizes brain skills, brain performance, and mental resilience as drivers of economic growth. Healthy brains power innovation, decision-making, and social cohesion, all critical factors in navigating future challenges such as aging populations, digital transformation, and climate-related stress.

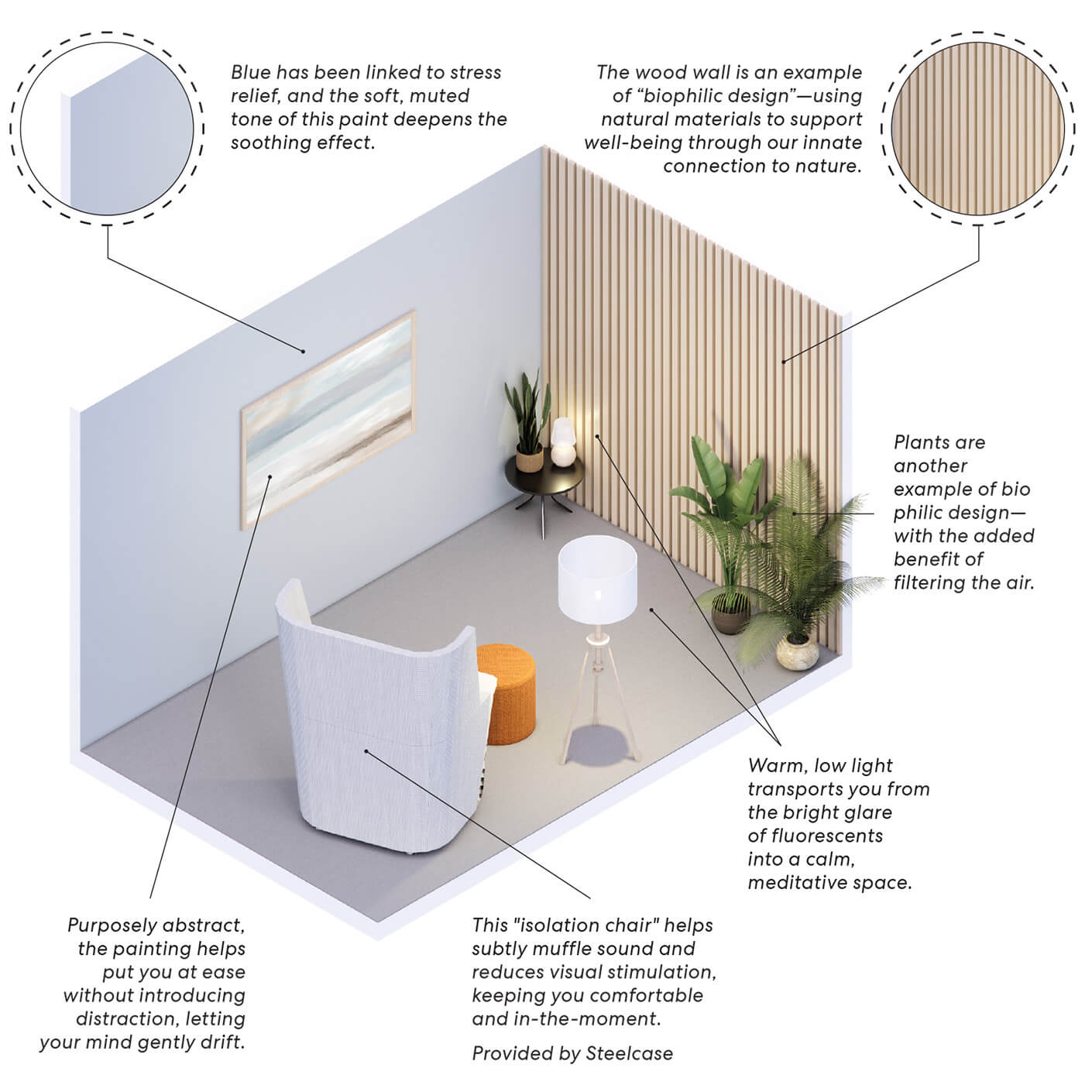

As architects, designers, and planners, we find ourselves in the unique position to directly impact these outcomes. The choices we make in shaping the built environment can either support or hinder brain health, in ways that might be surprising. A thoughtfully designed environment creates a permanent means to promote brain health, one that works independently but complements human-to-human interactions.