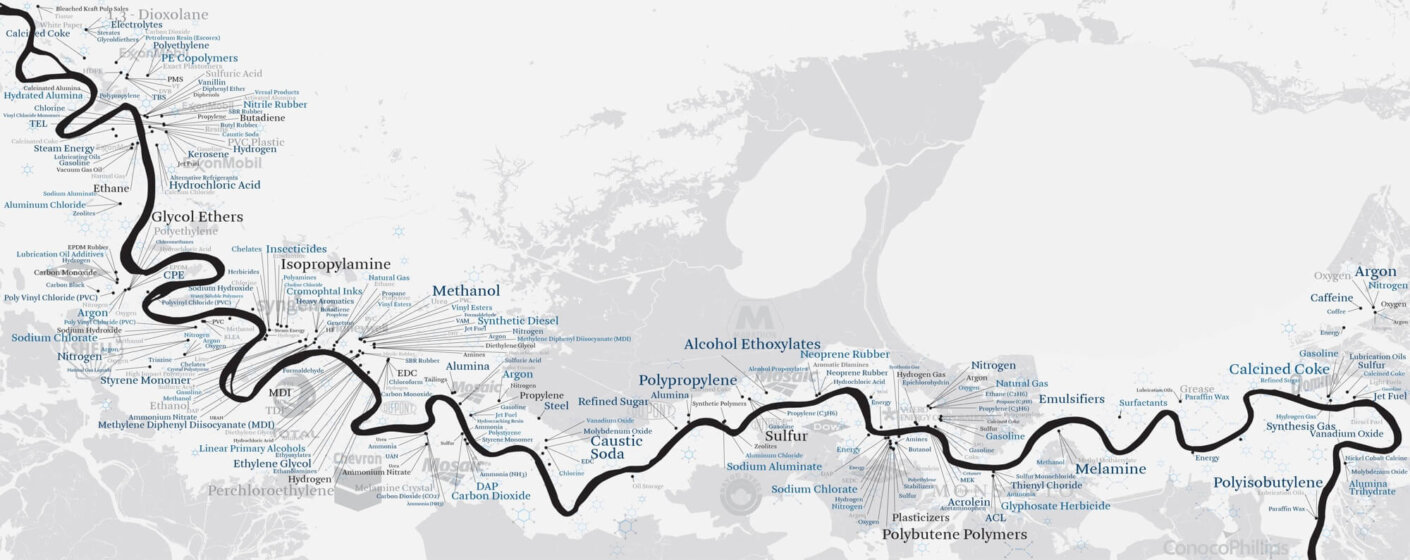

From toothbrushes and coffee makers to smartphones and laptops, nearly everything we use on a daily basis is made of plastic. Though seemingly innocuous, plastic contains hormone-disrupting chemicals like phthalates and bisphenols, which are absorbed into our blood stream just by touching them. Petroleum, or crude oil, is converted into the monomers that are used to make plastic and are in many commonly used building materials, including some waterproofing, countertops, and flooring.

From antimicrobials, flame retardants, solvents, heavy metals, and highly fluorinated chemicals, building materials are a constant source of exposure to these substances of concern. The cumulative effect these substances have on our body is known as body burden.

“When you walk into a building, you don’t think about the materials you’re being exposed to,” architect Tori Wickard tells Life of an Architect podcast. “That’s why it’s so important for designers to be mindful of material health.”