Conversations with Colleagues: John Stinson

A: I was always fascinated by how various components could come together to create something greater than the individual pieces themselves. To my mother’s despair, I explored this fascination at an early age by deconstructing household electronics, appliances, my own toys, and the sort. Though I was taking these items apart, my curiosity was based in how they were contrived so that I, too, could make something similar. I have always wanted to create, to make something that people feel is useful, beautiful, and important. The design profession gives me the opportunity to collaborate with various professionals and create places that do just that.

A: The world is a large and unfathomably complex place. As a design professional and steward of the built environment, I believe it is our responsibility to provide enriching and thoughtful spaces that address our diverse social landscape. In order to design at such a level, the design team itself must be diversified—otherwise, the same narrow bandwidth of issues will invariably be addressed the same way. Having been raised in a family with members from various backgrounds and differing viewpoints, I place value on the perspectives from which I myself cannot draw. Only by pulling our visions together can we reveal a more complete picture.

A: As a fresh architecture school graduate at Perkins&Will, I was lucky enough to start immediately on a project that would continue with me for the next eight years. The project was a Master Plan for Camp Southern Ground, an innovative camp envisioned by musician Zac Brown to educate children of all abilities and backgrounds in the outdoors. During the summer, the camp brings together typically-developing children as well as children with developmental differences, and children from underserved communities and military families. By bringing campers together from such a diverse range of backgrounds, Camp Southern Ground instills strong community bonds as children grow and learn together.

In addition to the summer camp, Camp Southern Ground also has a 12-month program to help veterans return to civilian living. Many face emotional and physical challenges upon returning from active duty, and this program helps them find answers to how they contribute meaningfully to relationships, work environments and their families when they get home.

I’ve worked on each of the buildings that have come to fruition since the master plan, from the dining hall to the first residential lodge, and currently the Campus Center Building. This project provides constant opportunities for my own personal growth and learning. I was able to learn about design considerations for children on the autism spectrum as well as military veterans living with both mental and physical challenges. Like this camp, we must keep in mind that we are an ever-diversifying culture, and we should strive to take into account the needs of those with different life experiences than our own.

A: I have worked on a variety of projects type—student unions, K-12 schools, restaurants, office buildings—and I meet their end users. One student, from George Mason University, had a huge impact on me, though we never even met.

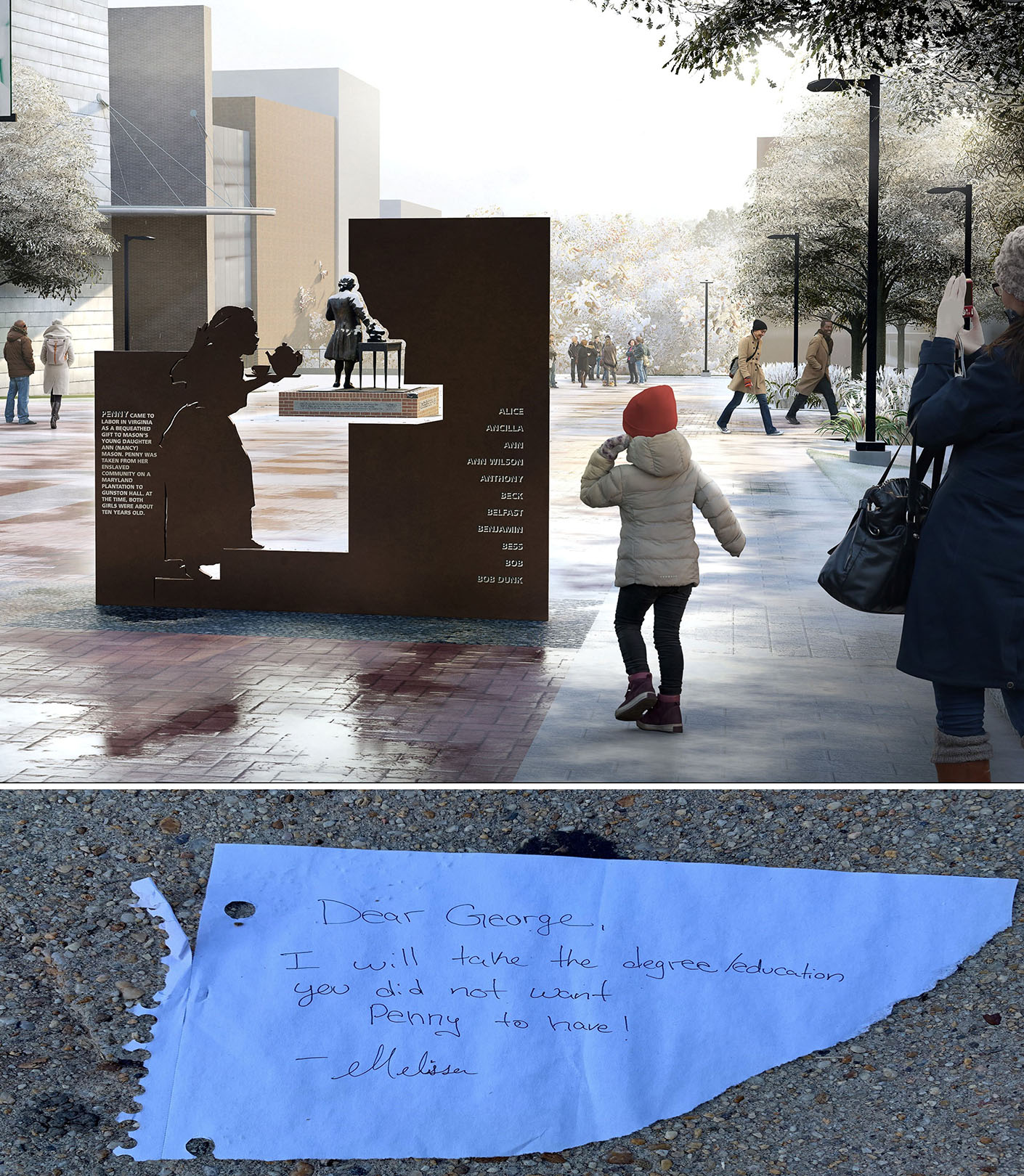

I joined the design team for the Memorial to the Enslaved People of George Mason last year, using my new-found knowledge in photogrammetry to help actualize the forms of the memorial. Our team spent days on site employing this imaging technology to create a digital reconstruction of the existing statue of the university’s namesake, founding father George Mason, in order to create alignments between new memorial elements and this existing statue. This project, which features figures of Mason’s slaves, highlights the voices of these traditionally hidden members of our collective history. The closest memorial panel to Mason’s statue itself features a young girl named Penny, who was removed from her family in Maryland and “gifted” to Mason’s daughter in Virginia as a companion. At several points along the plaza, viewers are asked to reflect on how power balances have changed since Mason’s time, prompting conversation and dialogue.

During a recent mock-up for the memorial panels, students and faculty had an opportunity to preview these sculptural elements that will be coming to campus, and some responded. The student who moved me left a note by Mason’s statue, which read, “I will take the degree/education that you did not want Penny to have!” I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to contribute to a project that’s not only a beautiful space for students and faculty, but also has meaning and purpose, inspiring thought, emotion and dialogue around histories of diversity in this country.