We created the E. Todd Wheeler Health Fellowship to offer hands-on professional development for emerging healthcare designers. Named for the late architect E. Todd Wheeler, a design visionary and Perkins&Will principal, this fellowship is awarded each year to up to five graduate interns. Selected recipients demonstrate a passion for advancing healthcare excellence through transformative built environments. In 2020, the COVID-19 global pandemic has brought healthcare spaces and their resource needs to the forefront of public discourse, amplifying the work of our 2020 fellows. Here’s the story of Christopher Koss, who worked in our Los Angeles studio during his fellowship.

Christopher Koss

A recent graduate of the architecture program at Kansas State University, Chris used his fellowship experience to explore two topics: How the acoustics of an environment affect patient well-being, and how the spaces we design impact the environment by generating waste. “This fellowship really opened so many doors for me, and encouraged such broad exploration,” he says. “Through my mentors and interaction with other leaders in the field, I was able to get a glimpse of the possibilities to come that most young designers aren’t exposed to.”

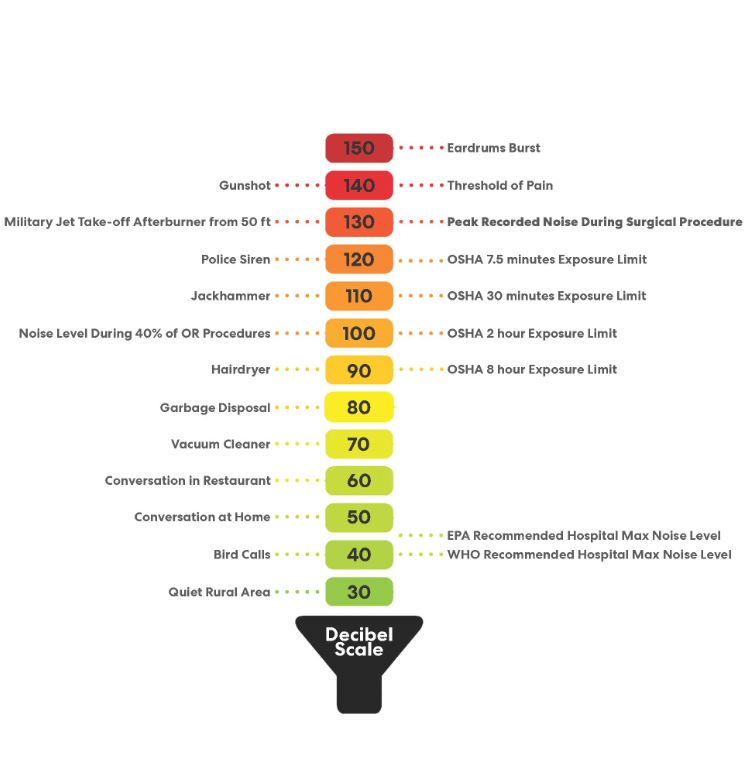

Chris researched noise levels in operating rooms in the U.S., China, and Iran. He discovered that, in each country, average noise levels in these critical spaces superseded both local and international recommendations, including those set by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The top producers of noise identified were HVAC systems and alarms. These led to a variety of physiological and psychological consequences, from fatigue and anxiety to impaired motor skills and longer recovery periods.

Through his exploration of both structural and technological solutions, Chris recommends that designers isolate anesthesia rooms from the main operating space, as that preliminary procedure causes the most aural disruption. “Isolating the noise in its own buffered space, as well as adding on elements like ceiling pads, allows us to absorb noise rather than just refract it.” Regarding technologies that could ameliorate the noise, he explored devices like noise cancelling headsets for surgeons that selectively cancel out unnecessary alarms and beeps. One of the most innovative is a haptic feedback device. Worn like a bracelet, it receives and sends vibrations to the wearer, replacing the need for live alarms while still alerting the responsive doctor or nurse.

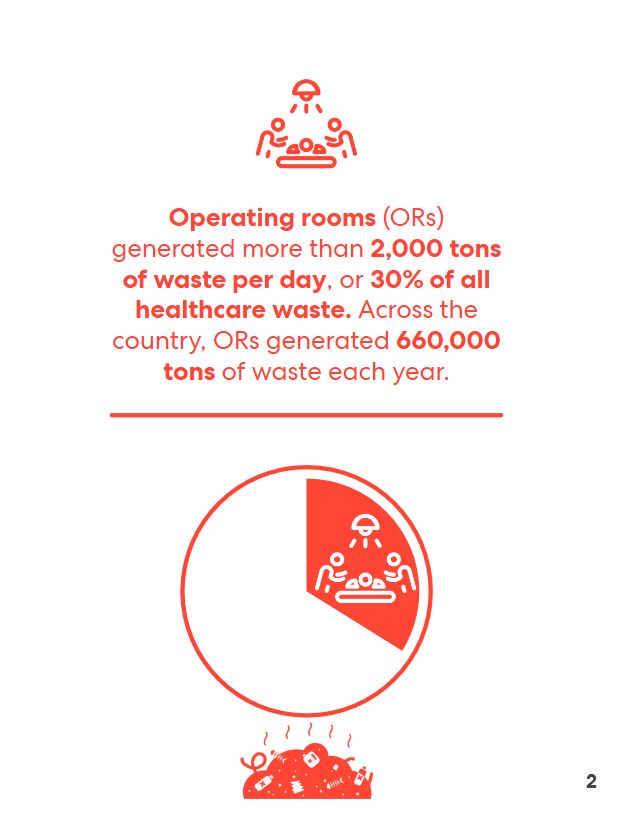

Chris also researched the financial and environmental consequences of hospital waste. Operating rooms produce a large amount of healthcare’s most expensive and dangerous waste type, Regulated Medical Waste (RMW), which is biohazardous. While this waste only makes up 18 percent of an operating room’s total, it requires 40 percent of the hospital’s waste budget to be safely processed. When combined with other waste streams, from disposable bed linens and hospital gowns to single-use medical instruments and packaging, the environmental and financial tolls can be exorbitant. Chris projects that if all his waste processing strategies were employed in a single operating room, that specific hospital could save nearly $70,000 per year, per room, and divert several tons of waste from landfills.

Chris’ research findings will inform our health practice, as they have the potential to tangibly improve the workplace experience of healthcare workers, assist in the recovery and treatment of patients, and help reduce our carbon footprint.

The power of design in each of Chris’ areas of inquiry is both inspiring and challenging. Chris’ solutions for practical yet flexible interventions in our hospitals are invaluable to our work in designing a better future. “If architecture was an equation, healthcare would be a constant variable,” he says, “the need for healing spaces will always be there, and this fellowship has shown me how I can make an impact on the future.”