This story is part of our insight series around the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The role of cultural institutions is in part to sift through a world of chaos, coalesce truths, and tell our unvarnished stories. The epitome of this may be our public libraries—the original keepers and interpreters of our collective data. Perhaps a closer look at how this one institution is responding might shed some light on its future and by extension the futures of other cultural entities.

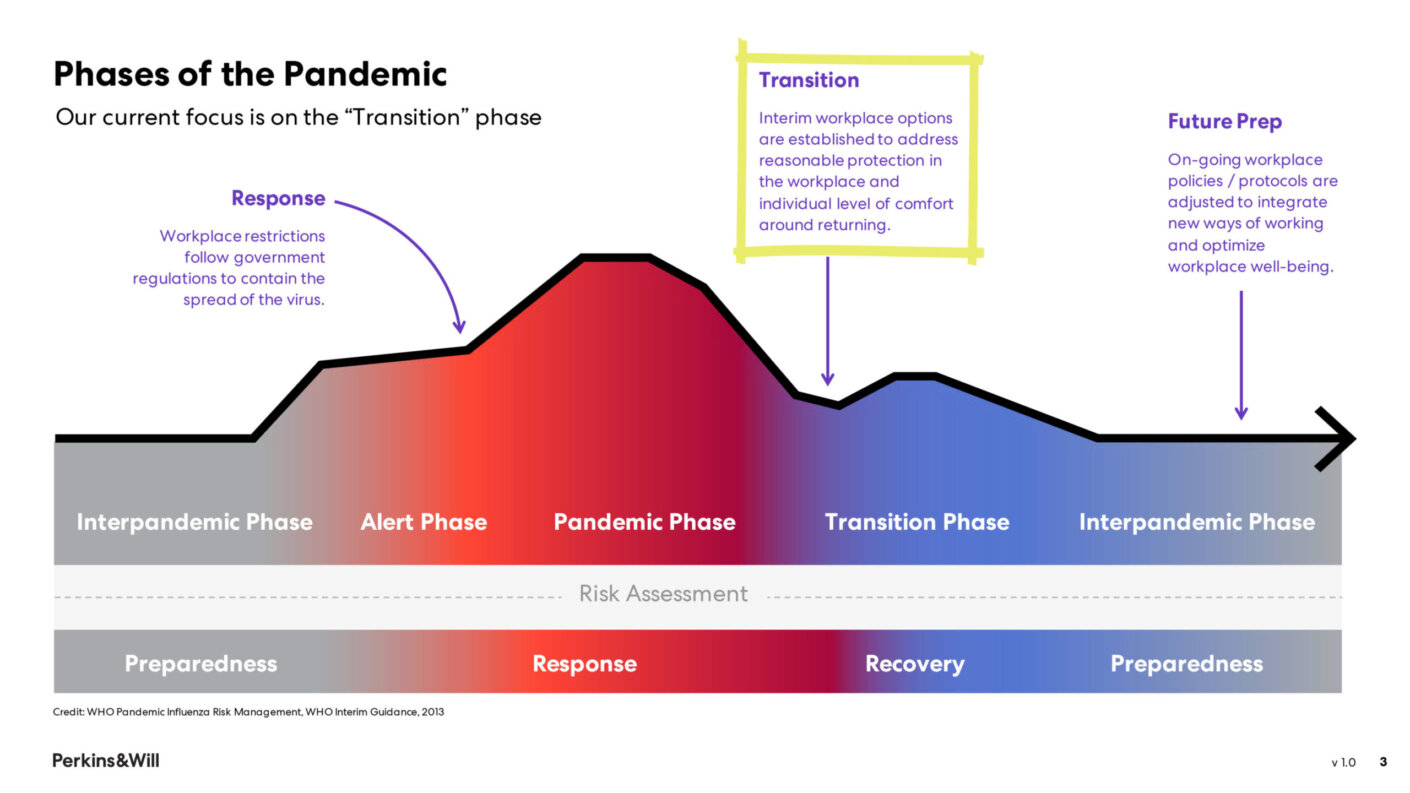

Before we go there, let’s revisit the guidelines for managing your way through the COVID-19 pandemic:

- You will have many symptoms if you get the virus, but you can also: get symptoms without getting the virus, get the virus without having any symptoms, be contagious without having symptoms, or be noncontagious with symptoms.

- You MUST NOT leave the house for any reason, but if you have a reason, you can leave the house.

- Masks are useless at protecting you against the virus, but you may have to wear one because it can save lives, but they may not work, but they may be mandatory, but maybe not.

Confused? We are inundated with ever-changing information and contradictory “facts” that compound uncertainty and leave many grasping for reliable information. Since distancing currently defines our resilience, we have seen culture—the shared values and experiences that bind us together—be transformed. Cultural institutions like libraries and other places for civic congregation have been indefinitely shuttered as we focus on life-or-death matters. Culture, however, does not disappear, because life without it is no life at all.