For a person with vision impairment, a groove in the pavement, the rise of a curb, or the bump of stones lining a path is a map forward. These lines, maybe gone unnoticed or taken for granted by someone with sight, can serve as a guide for the blind as they move about in the built environment.

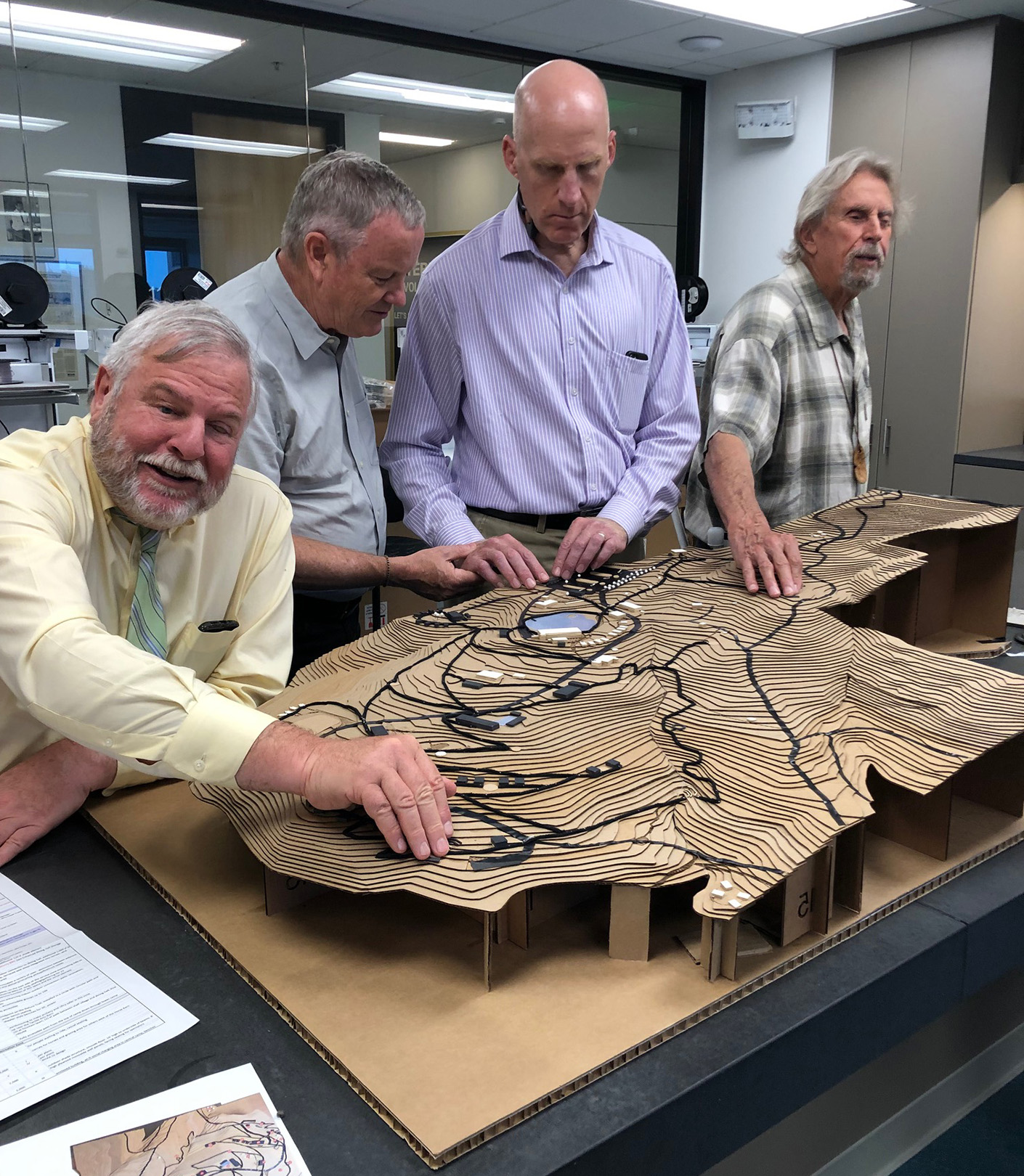

This was one of the most essential elements that architect and project manager Helen Schneider and her team learned on their first visit to Enchanted Hills, a camp and retreat in Napa, California, operated by LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired.

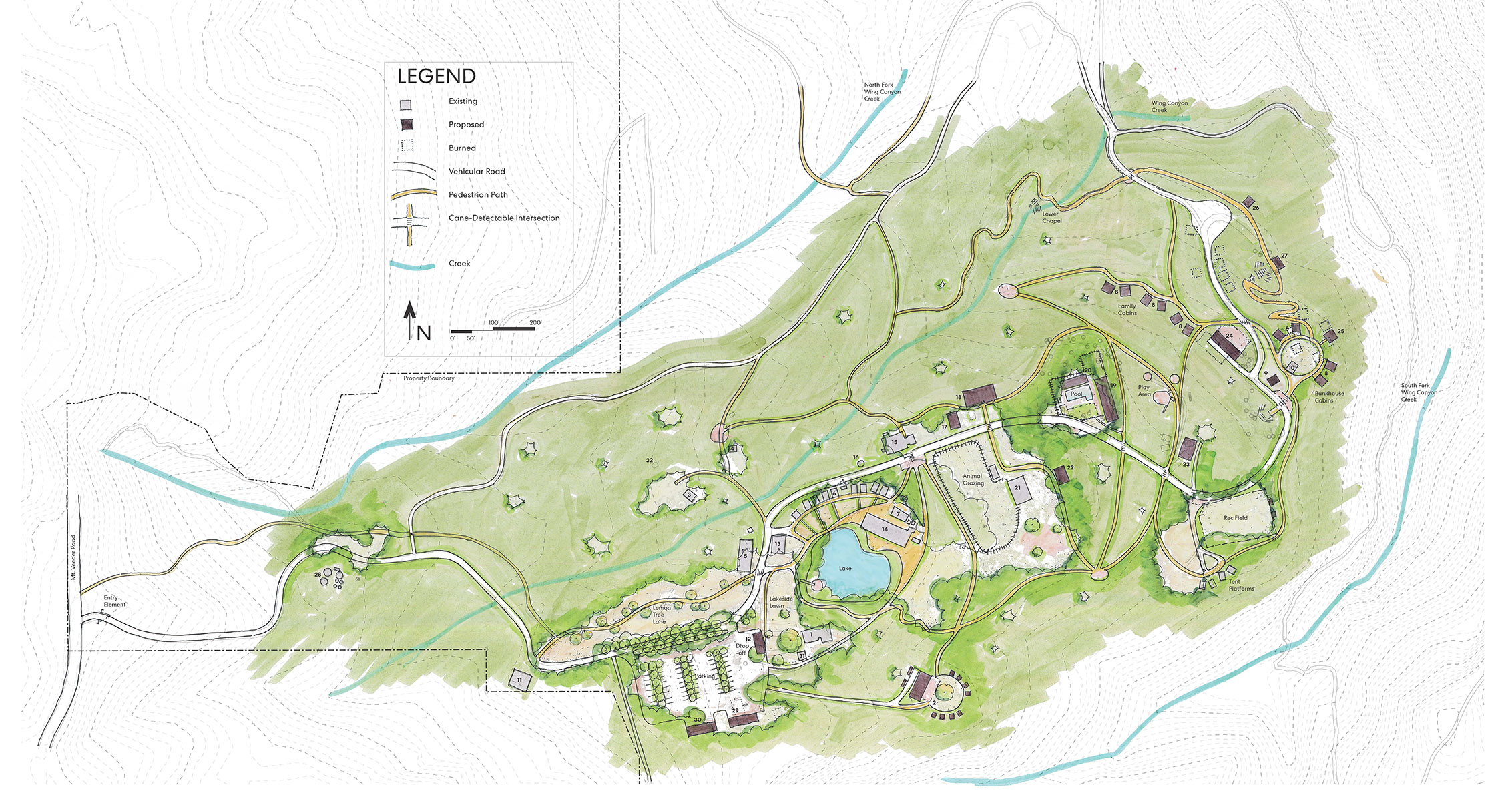

Since 1950, Enchanted Hills has been a haven for blind and visually impaired children, teens, adults, seniors, those who are deaf-blind, and all of their families. Situated on 311 rolling acres, the camp provides its visitors with a place to explore, learn, play, and gain confidence in their surroundings. Cared for by a tight-knit community, the camp was made of a patchwork of quirky buildings, many raised by volunteers over the years.

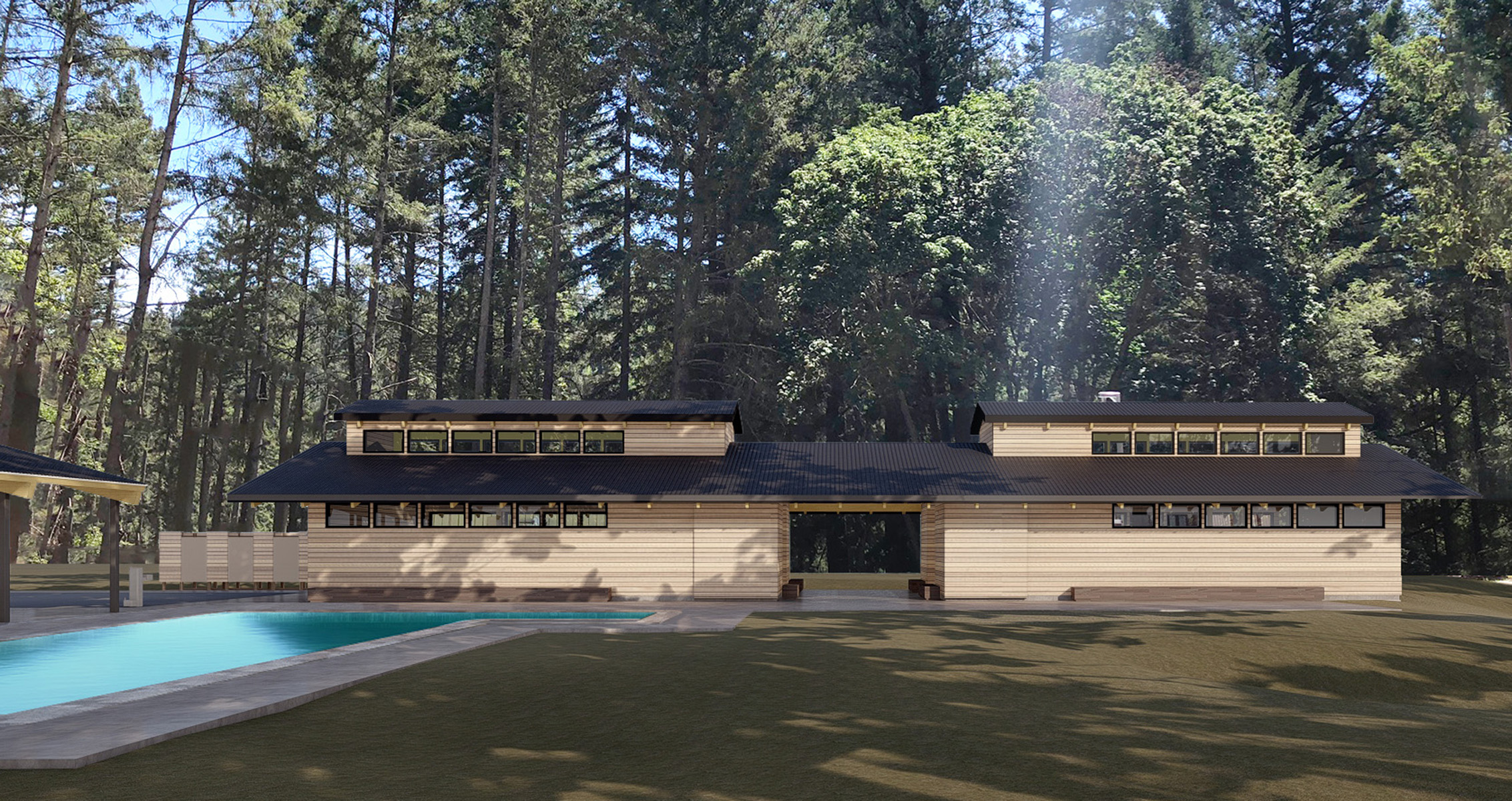

Devastatingly, in 2017, wildfire swept through Mount Veeder in Napa, destroying the lower camp and over 700 trees. The camp lost 20 structures—almost half of all buildings on the site. Rather than losing heart, the community was empowered to rebuild Enchanted Hills Camp better than ever. Our San Francisco studio’s Design Director, Peter Pfau, heard about the camp’s rebuilding efforts through a family friend. Initially, Helen and our team were hired to assess the fire damage for insurance purposes, but over time, new projects presented themselves. We were delighted to submit a proposal for, and ultimately win, the masterplan.