Peter Pfau: Design as Inquiry

Peter Pfau takes learning to be the measure of a worthwhile thing. That’s probably why architecture has for 44 years been its own reward. “I get to expand my mind with each project,” he says. Having taught as well for most of his career, he appreciates that there is always more to learn.

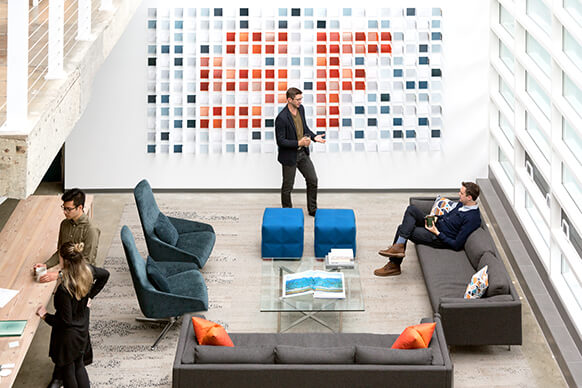

As design director of Perkins&Will’s San Francisco studio, Peter encourages the same curiosity and openness in his colleagues and clients. He invites others to experience architecture as he does—firsthand, in all its sensory detail—and approach design as a dance of craft and inquiry.

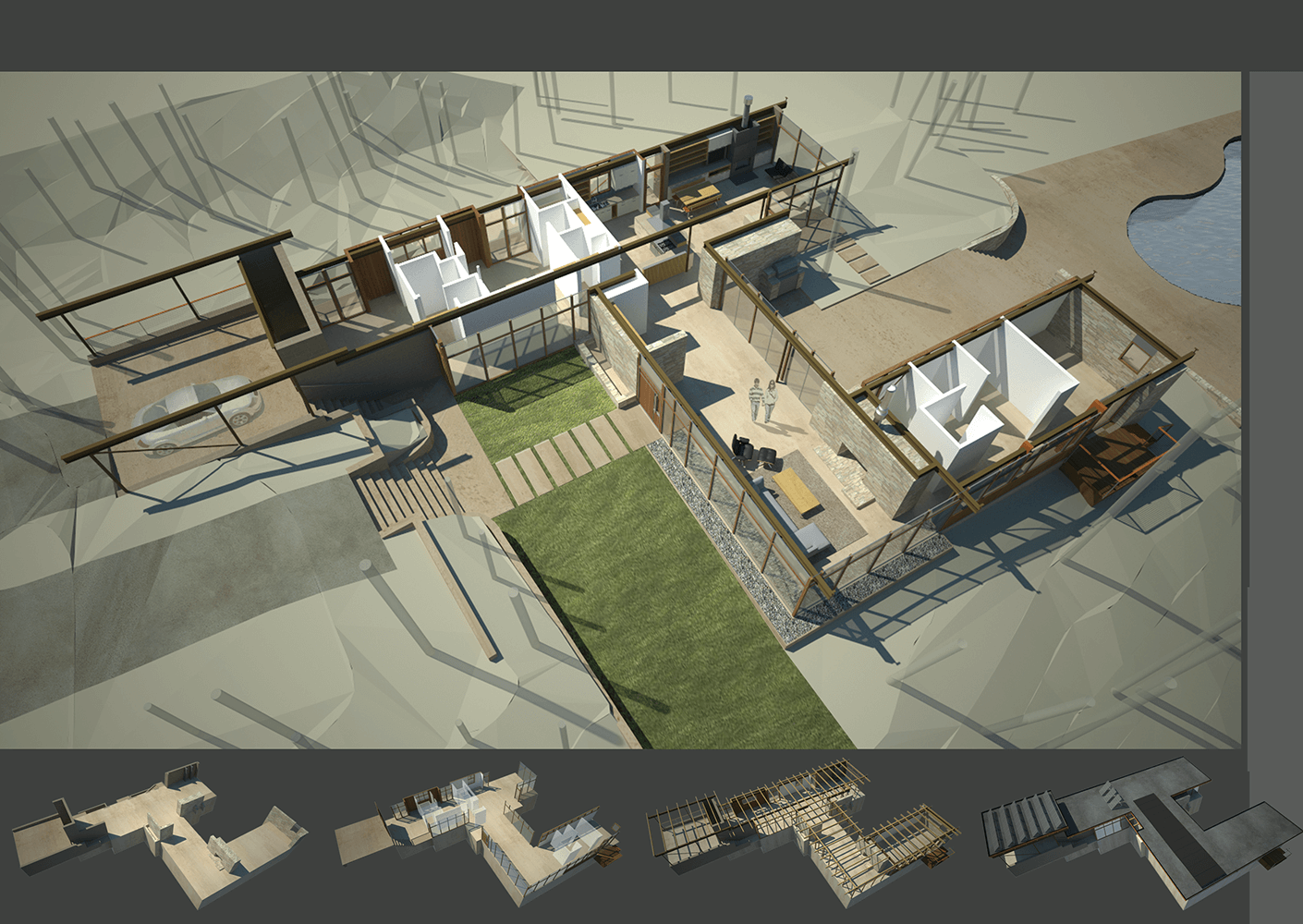

A student of California modernism, Peter prioritizes context, site, materials, and the relationships between indoor and outdoor spaces. He has a keen eye for the detailing of how materials come together and admires the expression of beams in Japanese architecture. “If you can express the true nature of materials in an honest way in a building, that has a compelling poetic aspect to me,” he says.

In the home he designed for his own family, the effect is that West Coast ease made famous by legendary architects Richard Neutra and Rudolph Schindler a century ago. Yet the joy of the process was having a playground for design, Peter says, trying far-out ideas and learning from misadventure. Beneath his calm demeanor, he leans more bohemian Schindler than buttoned-up Neutra.

After two decades as a founder and partner in his own firms, Peter leads the local studio of a global firm with his signature composure and honesty. When it comes to design, he maintains his maker’s creed: “Connect with and master the real thing.”

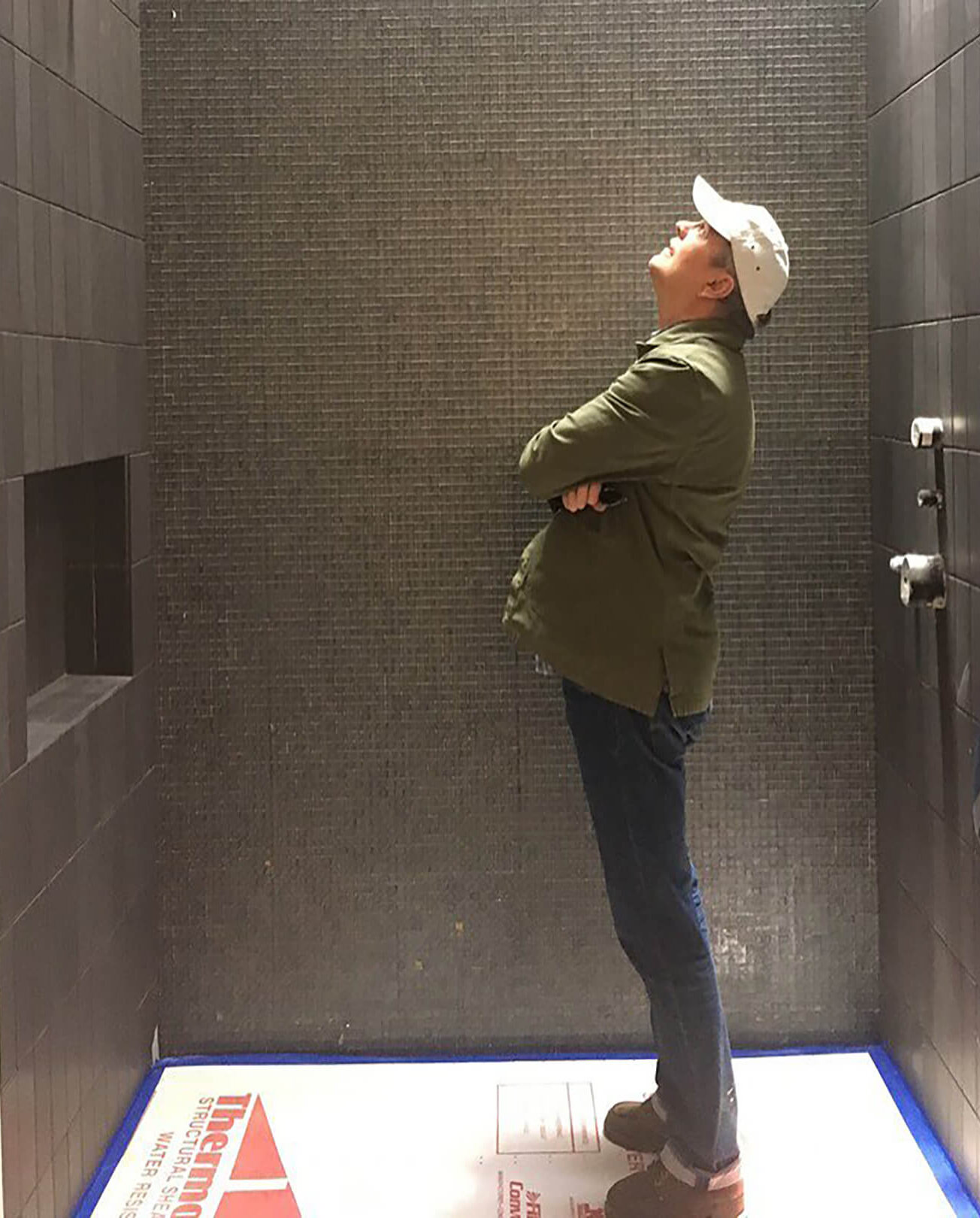

In other words, he urges teams to give deep consideration to the materiality and process of making reflected in their designs. He encourages all to build physical models and study design elements in real life, in real time. In particular, he invites those immersed in digital tools “to go out and actually touch a ledge or a sill or a door or a window and get a feel for what those things actually are.”

If this reconnaissance of the real sounds like a mode of inquiry, it should. Essential training for every architect, Peter says, it is the material aspect of design exploration. It is craft-driven inquiry.

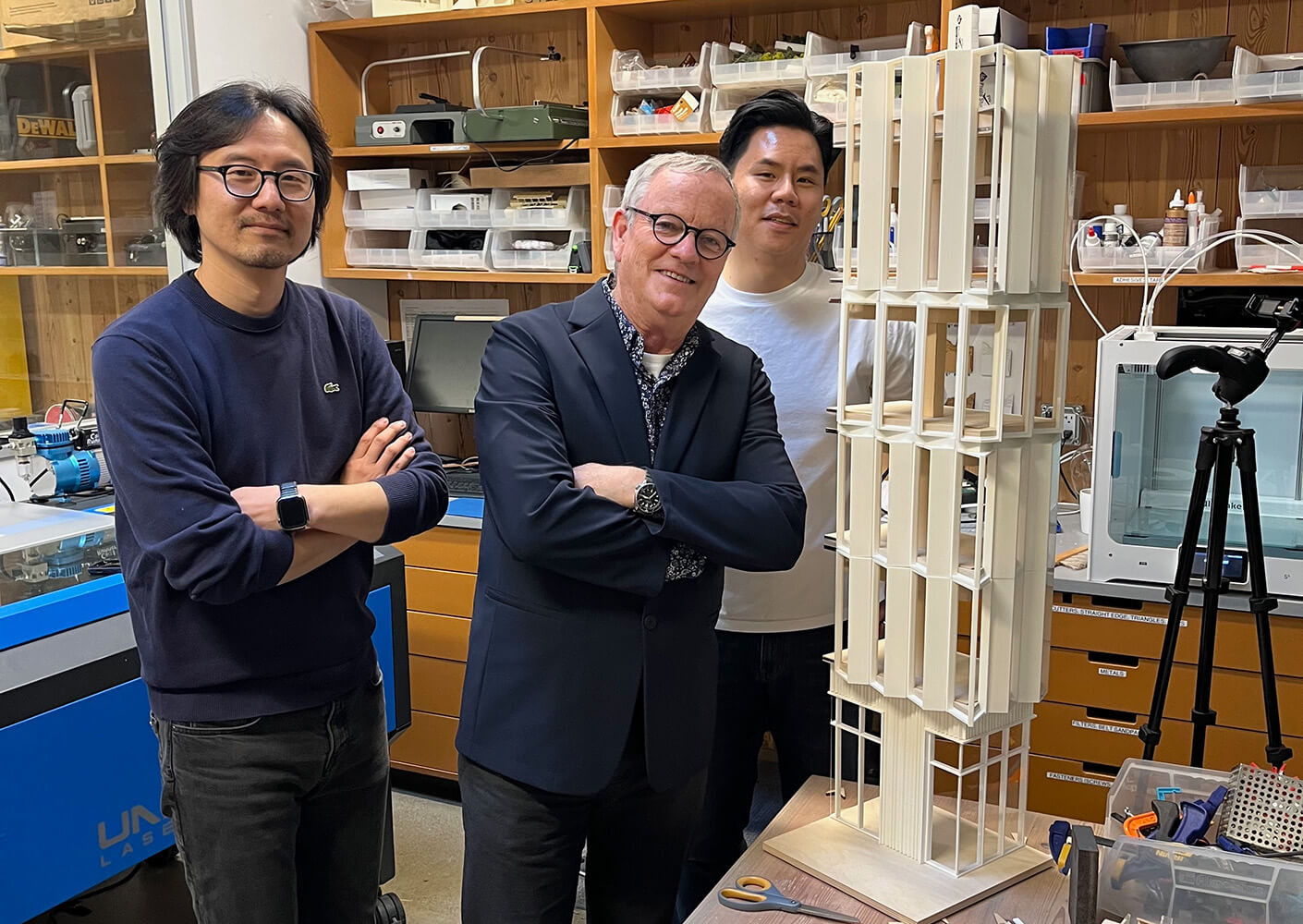

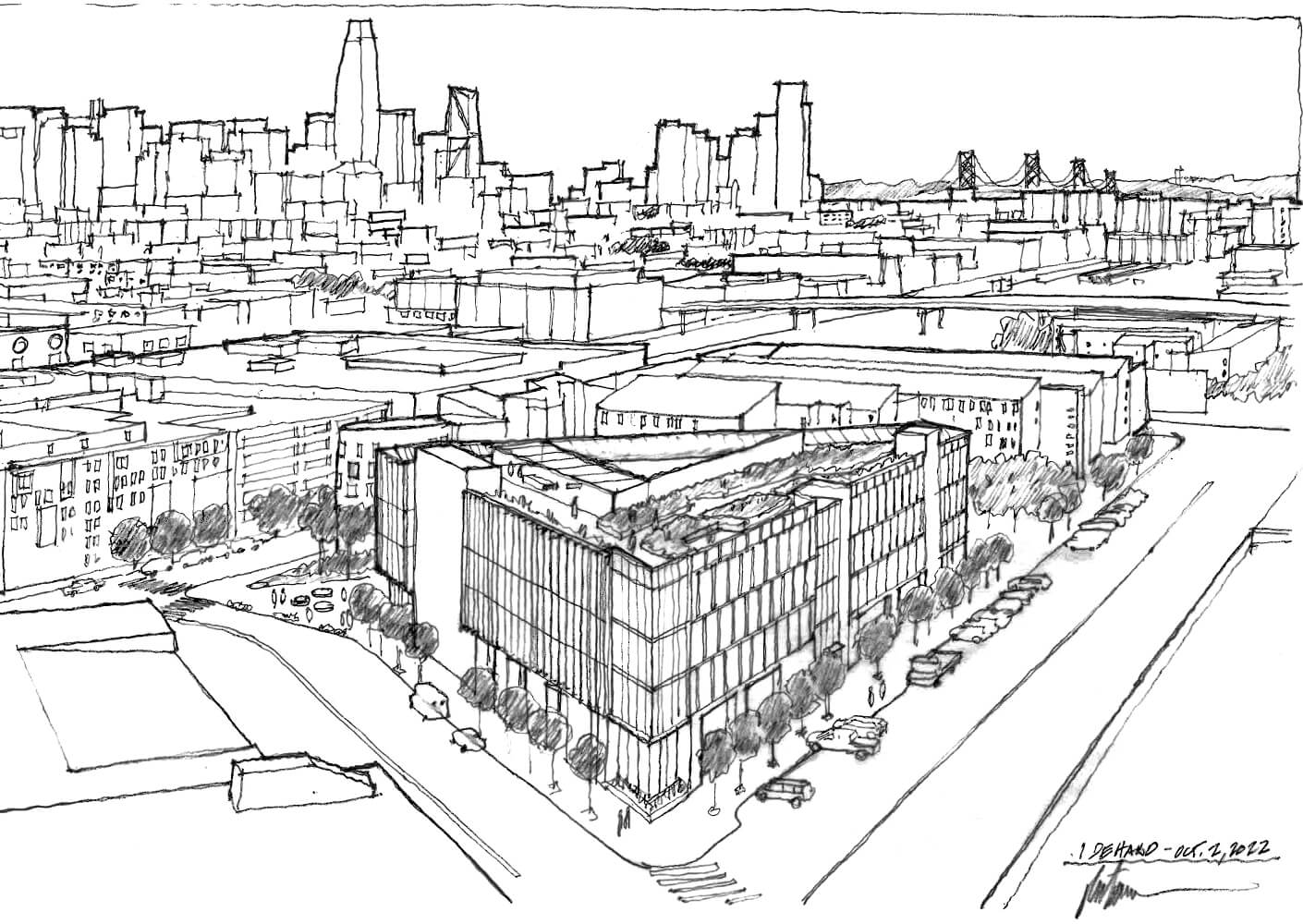

Peter ensures that craft drives inquiry in even unlikely project types. Speculative office buildings, for example, can default to assembly rather than architecture. The San Francisco studio’s design for 1 De Haro, however, is both the city’s first mass-timber project and unequivocal architecture.

Blocks from historic Showplace Square, 1 De Haro cuts a distinctive figure—one accentuated by a glass curtain wall, which showcases the warmth of the wood during the day and allows illumination of the block at night. Drawn to a fine point at the south corner, the curtain wall also broadcasts the appeal of the triangular site.

How to program the site edge for more than parking? How to cantilever over the culverts protected by a utilities right-of-way? How to attach the curtain wall to the structure? Every detail masks a web of interlocking inquiries, and we aren’t even through the front door.

Pivotal in terms of craft, the choice of mass timber was not a given. At the outset, the team inquired into concrete, steel, and wood. The studio had one mass-timber building under its belt; the client, SKS Partners, had none. So the process began with Peter and team convincing SKS to “race the alternatives.”

The race took the design team and client to Chibougamau, Canada, in central Québec, where they toured the mass-timber manufacturer’s forest and saw how the wood is harvested. They also learned how the computer cuts the wood, so they could start to game out the building’s structural system.

It turns out mass timber can be manufactured to within a “ridiculously accurate” 16th-inch tolerance. Knowledge of this precision led the team to inquiries about metal connectors that could hold the wood together. But no one had done this before: how would fireproofing codes apply to the metal connectors?

The team consulted experts about the natural fireproofing properties of wood. (Yes, it’s true.) Then in collaboration with the digital fabricator, they found a way, given the precision, to hide the connectors inside the wood and slip the pieces together during assembly. The result is an object lesson in craft, fine-tuned by inquiry, making architecture out of assembly.

— Peter Pfau

Peter comes by his attention to craft honestly. He remembers that his dad built everything in their family’s home. But he does not let his maker’s respect for the “real thing” limit his inquiry. He embraces all modes of exploration, including reading.

In researching a plan of the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, for example, he read every book he could get his hands on—about the geology, the National Forest Service, the Santa Fe Railroad, the seven Indigenous tribes for whom the place is sacred. The depth of the reading helped shift the team’s mindset, he recalls, and evolve the direction of the design.

Like the bespoke curtain wall of his (until recently) Marin County home: Peter wanted to float the mass-timber roof on the glass enclosure by sitting the roof on steel laterally braced beams. “But I pretty quickly realized that the beams go flying through my glass walls in a bunch of places.”

Not a problem but an opportunity, as they say. Intersections and corners being a bit of an obsession with Peter, he came up with an aesthetic for sealing the glass around each beam.

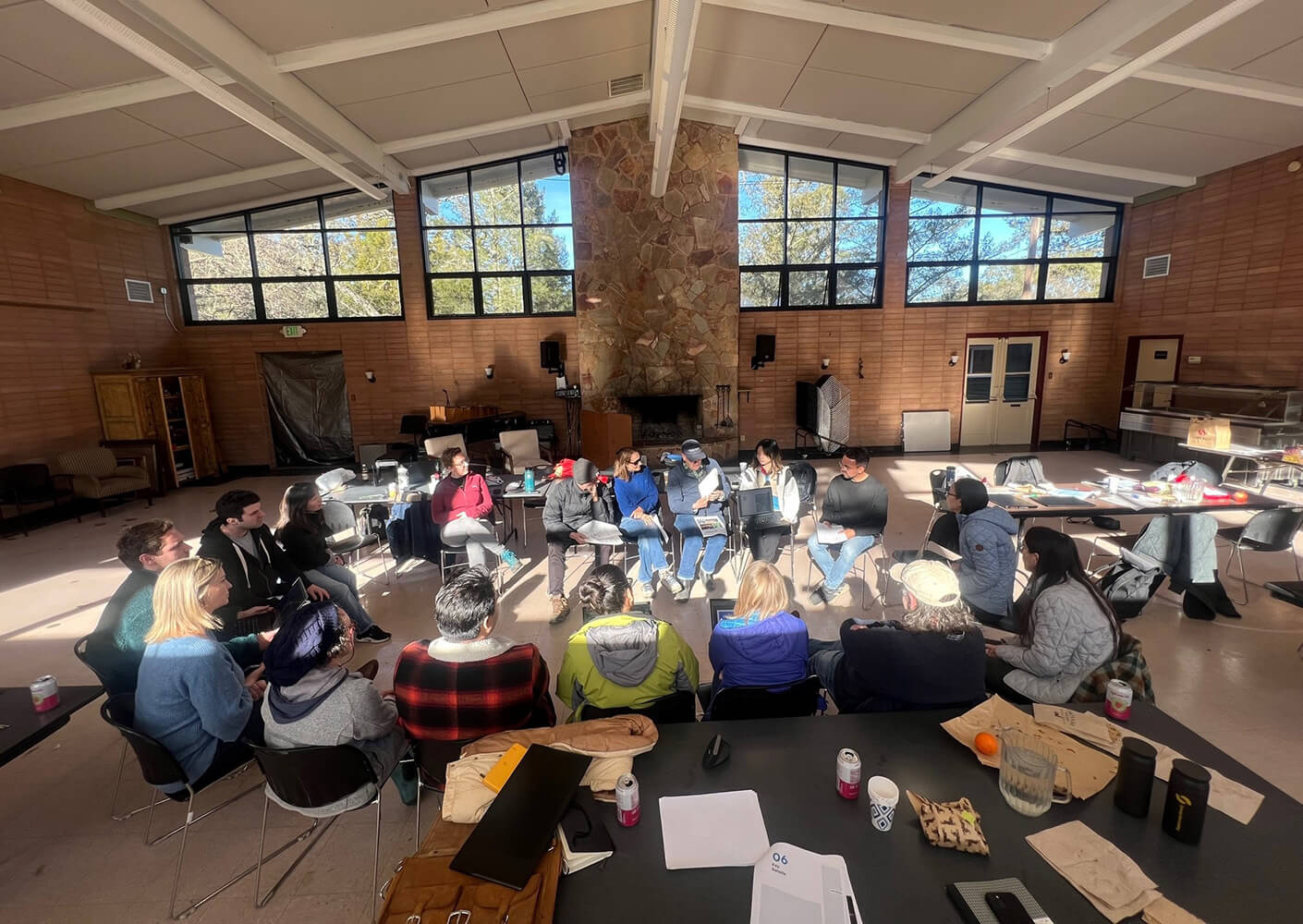

The 2017 wildfires in Napa and Sonoma counties destroyed half the buildings at Enchanted Hills Camp, run for 70 years by San Francisco’s LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired. The process of restoring and redesigning the summer camp over the last few years has transformed the studio’s approach to social equity. It has “shattered our standard toolkit,” Peter admits.

Steeped in the visual bias of sighted people and Western architecture, the architect’s standard toolkit values drawing and views and light. It relies on perspectives, diagrams, and data visualization to develop and communicate design concepts. The Enchanted Hills community experiences the world by other means.

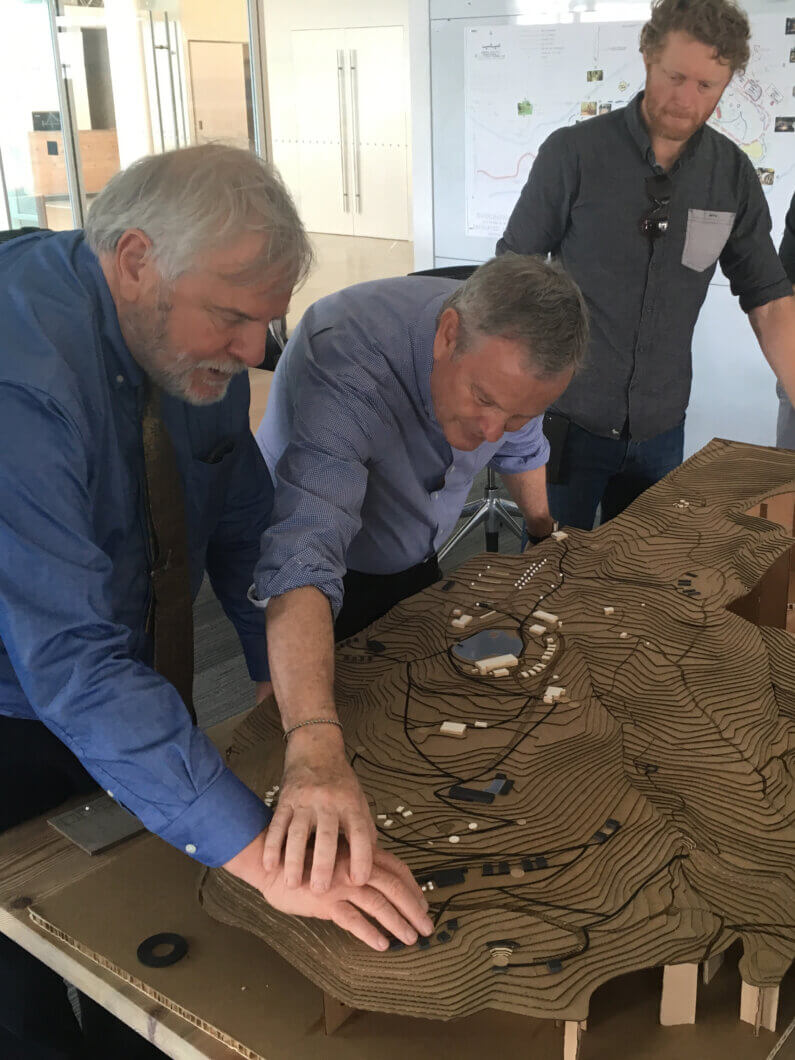

Not only did the design team learn to understand the camp through the experience of campers and visitors—for example, learning to hear the sensation-rich soundscape of the place—but they also evolved their engagement tools and their techniques for presenting the design.

In every presentation, they strove for the right balance between verbal description and the read of bumpy drawings. “It’s been a whole learning curve to find out how much data can be taken in through the fingertips,” Peter says.

Tactile models are a staple of design development, but how to communicate where to find braille on a building? Similarly, how to communicate the difference between a path and a building on a 2-D map? Through a strong back-and-forth the team adapted the scale model and made their two-dimensional drawings tactile as well.

If all goes well, they will apply the lessons learned to a custom 3-D model that will live on-site for blind and low-vision visitors to touch and orient themselves.

— Peter Pfau

In practice, the will of the project is the coordination of many wills, or, as Peter describes it, the purposeful shepherding of parties and personalities through shared values toward a common goal. “It’s not for the faint of heart,” he says of the design leadership part of his job.

He attributes his clients’ trust in him to his decades of experience of course, but also to his willingness to speak honestly at every difficult decision. And his colleagues trust him for the very same reason. “I’m a really calm, reasonable person with strong opinions about design,” Peter says matter-of-factly. “It isn’t a glamorous superpower, but it is my superpower.”