One With Nature: How the Architecture of Ryan Bussard Espouses the Environment

Ryan Bussard has been living in Seattle since 2004, when he moved with his family from New York City. Part of what drew him West was the direct connection to nature—the sheer variety of environments that can be accessed easily from the city: glaciers, alpine meadows, high desert country, and temperate rainforest.

Bussard is continuously impressed by the culture of the Pacific Northwest. Here, radical ideas on sustainability and innovation are embraced both socially and politically. It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that his designs prioritize these ideals—whether it’s a university building, a high-rise, a laboratory, or a library. “Sustainability should be meaningful, visible, and educational,” he says, “but there is plenty of room for moments of beauty, too.”

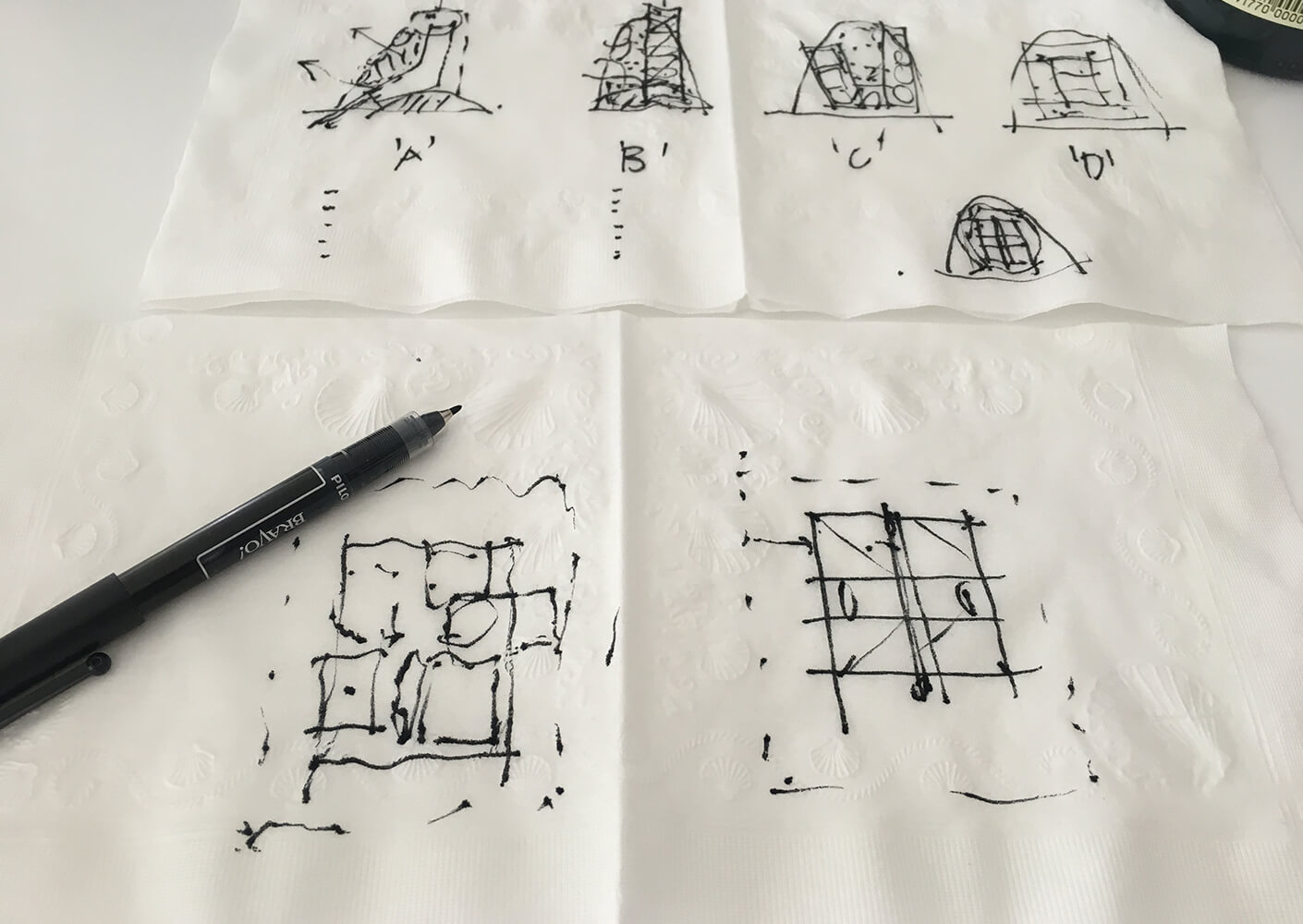

To meet his goal of combining aesthetics and sustainability, Bussard often starts with a personal exploration: “For me, the most interesting time to work on a project is the very beginning. It is incredibly formative—this moment where you’re trying to think about new ideas and how to develop and nurture them.” He’s the kind of architect whose work is shaped by his lived experience of the built environment. Just as he considers how his buildings should meet the ground, touch the sky, and achieve their user’s needs, he also thinks about the long arc of architectural history and how other designers have developed innovative solutions to complex problems.

Many of Bussard’s favorite projects are collaborations with clients near and far who share his social and environmental ethos. One client was the Water Institute of the Gulf, a Baton Rouge-based research hub focused on tackling the challenging conditions facing the Gulf coastline and its waterways—including the Mississippi River. The river’s banks are the lifeblood of the city that surrounds it, and the new Water Campus there has become an important hub for the environmental science community. In fact, the Mississippi River and its interface with the Gulf have long offered researchers crucial insight into the impacts of the global climate crisis.

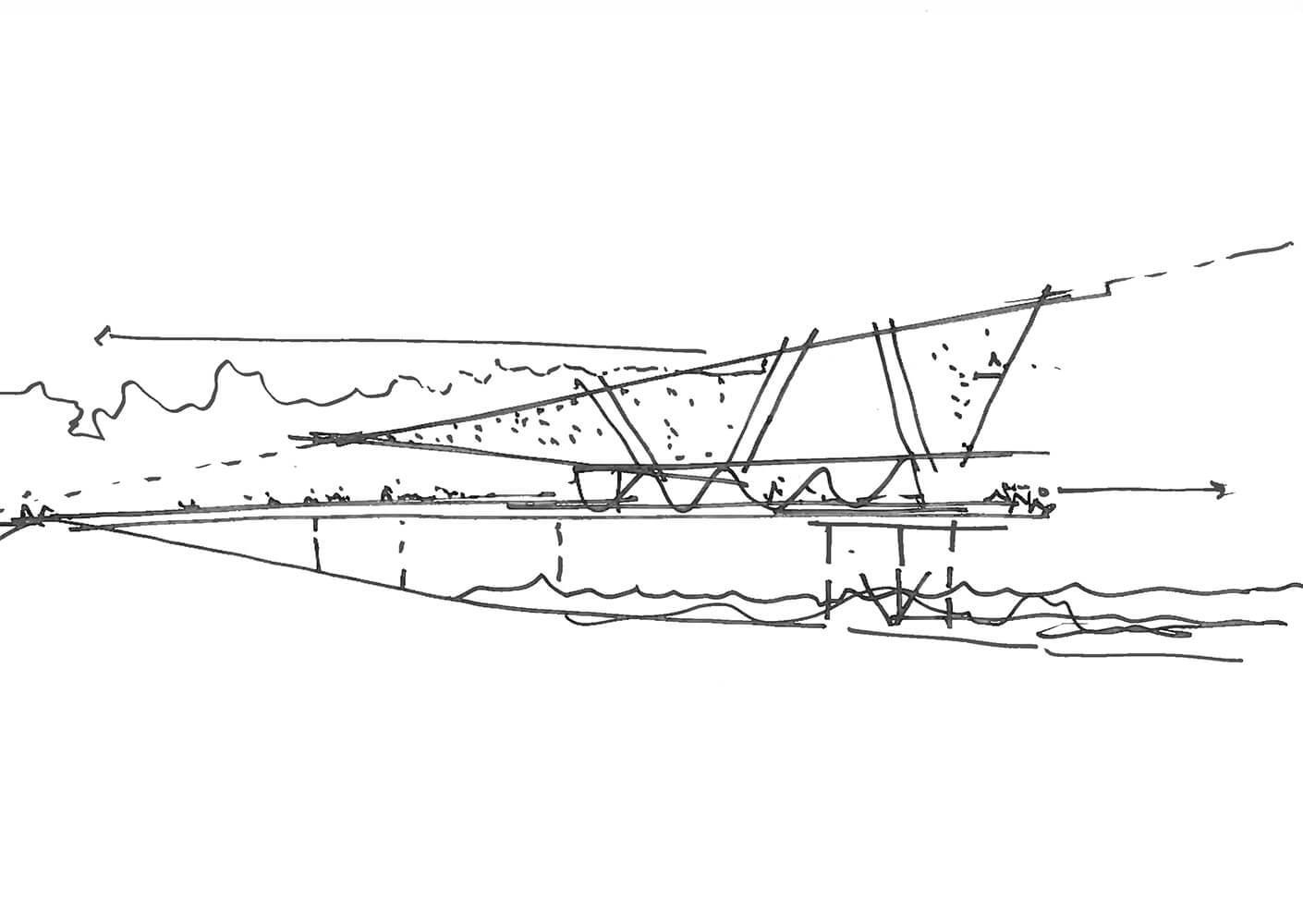

The Water Campus site—home to the Center for Coastal and Deltaic Solutions, which Bussard designed—is a former condemned river pier that once served as a major industrial port. It offers stunning views of the Mississippi delta, but its precarious and narrow foundations put it at risk for seasonal flooding. “When analyzing the river and its behavior, we saw that the entire pier was incredibly close to the high river current,” says Bussard. “But we were determined to create a truly resilient building, one that would keep researchers and their vital work safe in the face of even the strongest surges.” To accomplish this, the Center rises above the pier, high above the flood line. Its glassy façade and bright architectural supports reflect the constantly changing light bouncing off the river’s surface and invite researchers and visitors to view the subject that shapes their daily work.

“It became clear that public accessibility was a key theme for Baton Rouge residents, a value that also aligns directly with our work at Perkins&Will,” Bussard says. So, in his design submission for the national competition, he prioritized the people’s civic pride in the riverfront: The plan opened much of the newly reinforced pier to the public, rather than to campus researchers alone. And, the new public space allows for direct access to the water, a rare opportunity in any urban setting. “By returning the land to the public, we responded to a longing for remembrance of the city’s roots and the local ecology. Simple, equitable occupancy of land did so much more for the city than we imagined.”

This blending of sustainability and aesthetics is also a hallmark of Bussard’s science and technology projects, like the Center for Novel Therapeutics in San Diego, California, A state-of-the-art laboratory specializing in cancer research, the Center houses both university-level and commercial research initiatives in a new, blended typology. But above all, it’s a living lab that challenges the sterile status quo of laboratory design.

For that project, Bussard focused on facilitating greater energy independence. Turning his attention to the generous atrium skylight that illuminates the building, for example, he sourced advanced photovoltaic panels that are transparent enough to allow daylight to penetrate while also maximizing sunlight capture. The resulting effect is soft, calming, natural light throughout the atrium, and an independent energy source for the laboratory.

Bussard understands the realities of climate change and the role the built environment plays in it. But through intentional design and creative problem-solving, he and the team responsibly create spaces of beauty. With rich textural detail, he’s flipping the script: Bussard brings site-specific aesthetics to each project through marriages of light and nature, and connects them to human needs and behaviors. His portfolio of labs, educational spaces, and cultural centers are inspired by the human spirit, reinvigorating our imagination and challenging our assumptions about what architecture for science and tech can be.

“Design is meant to peacefully coexist with our natural environment, no matter what city, town, or site we choose,” he says. “My designs follow wherever the landscape may lead.”