Ferry Building

In the early 20th century, tens of millions of travelers took their first steps in San Francisco in the Ferry Building. Though the 1898 Beaux Arts structure stretching along the San Francisco Bay had survived a 1906 earthquake and fire, it could not outrun the advent of the automobile. Ferry ridership plummeted with the opening of the Golden Gate and Bay bridges in the 1930s. A mid-20th century conversion of the transit hub into generic office space literally covered its interior and exterior grandeur.

Our adaptive transformation restored the Ferry Building as a quintessential San Francisco destination. We brought new life to the historic landmark by elevating its original design and introducing a diverse mix of commercial uses. Through the city’s economic swings, the project has continued to thrive. Filled with companies occupying its Class A offices, patrons of its farmer markets, artisan food merchants, and independent restaurants, passersby enjoying its promenade, and passengers of a reinvigorated ferry service, the Ferry Building has a long future ahead as the jewel of the waterfront.

Though the 1950s office conversion spared the Ferry Building from demolition, it did little else of benefit. An inserted floor plate truncated its grand nave spanning the second and third floors, while retrofit ceiling and wall finishes covered skylights and windows. Nondescript cladding obscured much of the building’s exterior while the Embarcadero Freeway to its immediate west cut off its connection to downtown.

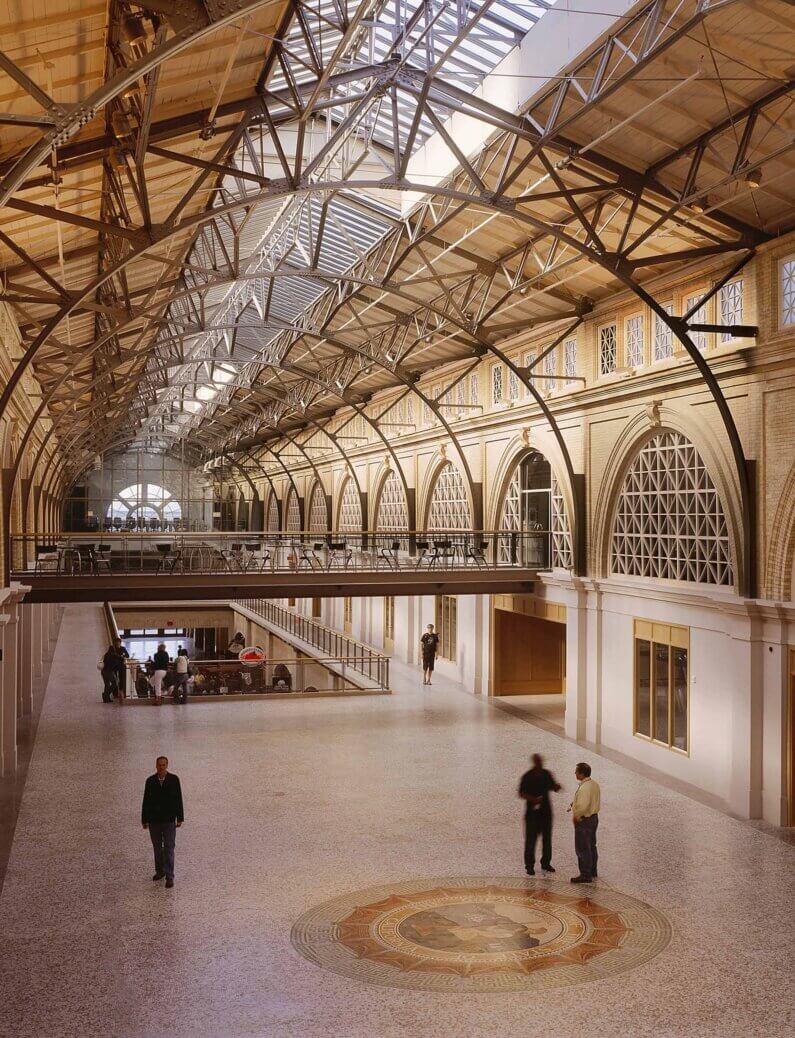

The freeway’s removal following damage from the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake helped stir interest in the Ferry Building. In response to a 1998 competition to reimagine the landmark terminal and activate the city’s waterfront, we and the developer made a bold proposal: We would not only reopen the nave but also cut out large swathes of the second floor to connect the nave to the ground floor. This would visually unite the interior and allow natural light to reach the entire building core.

Though our proposal significantly reduced the amount of leasable floor area, we knew this was the right move for the project’s long-term viability. Though the State Historic Preservation Office and National Park Services were hesitant to alter the original floor configuration, we respectfully negotiated the length of the second-floor openings to five bays on either side of the nave’s center, marked by the restored floor mosaic of the state seal.

Fortunately, the midcentury renovation had left intact portions of the nave’s brick arcade, albeit with the arched windows infilled with drywall. Rebuilding the arches in brick and the geometric window mullions in wood was ideal, but economically untenable. Instead, we completed the arcade with 22-foot-tall glass fiber panels cast from a mold of a surviving arch, and brush-painted aluminum window mullions to create a woodlike texture. Where the mosaic tile floors had been removed or damaged over time, we used material salvaged from the second-floor cutouts. We also restored the grand arcade of metal trusses spanning the nave.

Outside, we recreated the look of the building’s original Colusa sandstone masonry with thin brick painted in what would become our namesake Ferry Building Gray, by Sherwin-Williams. On the bay side, we added arched windows recalling the lunettes of the original’s grand waiting room down the length of the façade, restoring the building’s historic character.

Our deferential and detailed approach helped garner a $23.5 million historic tax credit for the approximately $110.5 million project.

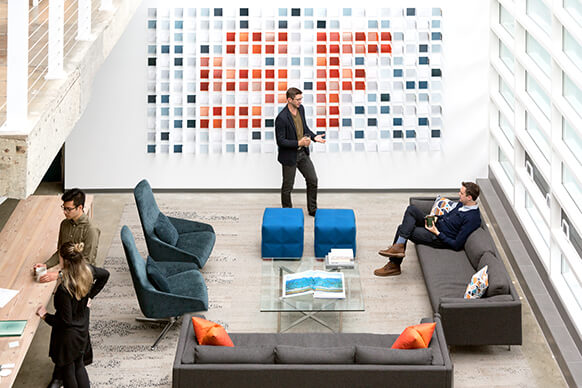

Within the first year of its reopening in 2003, the Ferry Building was an economic success. Residents and tourists alike enjoy its year-round farmers market, renowned restaurants, and eye candy of food stalls and shops filling the ground floor. The open and breathtaking nave has made the second floor a desirable event venue. To increase the amount of leasable office area, we enclosed the nave’s north and south ends with glass curtain walls to create additional space for world-class tenants. On the bay side, we extended the second floor with a 10-foot, gangway-inspired cantilever, with the added benefit of creating a shaded public walkway on the plaza.

On the city side, the Ferry Building’s repaired arched and clerestory windows offer a sense of permeability, connecting the density of the cityscape with the openness of the Bay. Anyone can easily access and enjoy the waterfront, thanks to a 30-foot-wide promenade we wrapped around the building’s north and south ends, making the plaza a popular gathering place even on nonmarket days. And, in a reversal of fate, increasing freeway congestion on the bridges has made ferry riding popular again.

By respecting the historic architecture of the Ferry Building with strategic tweaks to enhance public access and economic vitality, our team of developers, engineers, and architects has created a memorable and authentic community destination. The project truly serves the people and city of San Francisco.