On a recent walk on the Atlanta BeltLine Westside Trail, my son excitedly pointed out a bluebird next to the trail. As we enjoyed the song of this bluebird, I reflected on how wonderful it is to experience nature in the city. The dance of colorful butterflies, the soaring flight of a hawk, all of these natural wonders depend on the plants we preserve and plant in our parks, homes, and campuses. We are part of an interconnected web of life, and the decisions we make have a profound impact on the other species in this web.

Recent research published in Science shows bird populations have plunged since 1970. With the loss of nearly 3 billion across North America, that’s an overall decline of 29 percent. When forests and meadows are replaced with roads and buildings, valuable habitat and food sources for wildlife are lost. We can, however, maintain this habitat through strategic preservation of habitats in developed areas and by the types of plants that are planted in the built environment.

The return of the Atala butterfly is a great example of how plant selections impact the wider ecosystem. In South Florida in the 1970s, entomologists started to see the species they thought was extinct. It turns out that the sole host plant for the butterfly was a hot new plant in ornamental landscapes, the coontie. In fact, the plant wasn’t new at all. It was a native plant that had been removed from the wild over the previous century. The return of the Atala was directly tied to the decision to plant coontie in landscapes. So you see how our landscape choices can meet our aesthetic desires while also supporting the ecosystem we are part of.

We applied this principle in the design of the Atlanta BeltLine Westside Trail, a linear arboretum with 1,417 new trees and 17.5 acres of native Piedmont meadows. A typical linear trail in the region would have acres of sterile turf grass with little habitat benefit for wildlife. Instead, thousands of Atlantans can now encounter a rich variety of plants and animals as they stroll the Westside Trail. The presence of bluebirds, like the one my son spotted, is tied directly to the native plants along the trail. These “native plants” are the indigenous species that existed in the area before Europeans arrived, and, like the coontie attracts the Atala, they attract the insects the birds eat. Without these plants, there are no insects, and without insects, the birds don’t have food to eat. So many animals depend on insects for food that without the right plants to sustain them, the web of life is broken.

In a fascinating study, entomologist Doug Tallamy discovered that a native oak tree supports 557 species of caterpillars—a key bird food—while ginkgo trees support no caterpillar species. Non-native plants like the ginkgo usually have chemicals in their tissues that keep native insects at bay. In the study, the researchers demonstrated that there is a clear link between the number of native plants in a landscape and the success of the Carolina chickadee, a common bird across the Eastern United States. When the native plant biomass exceeds 70 percent within a landscape, chickadees have a chance to reproduce and sustain their local population. Imagine the potential for other birds to thrive if landscapes featured more native plants.

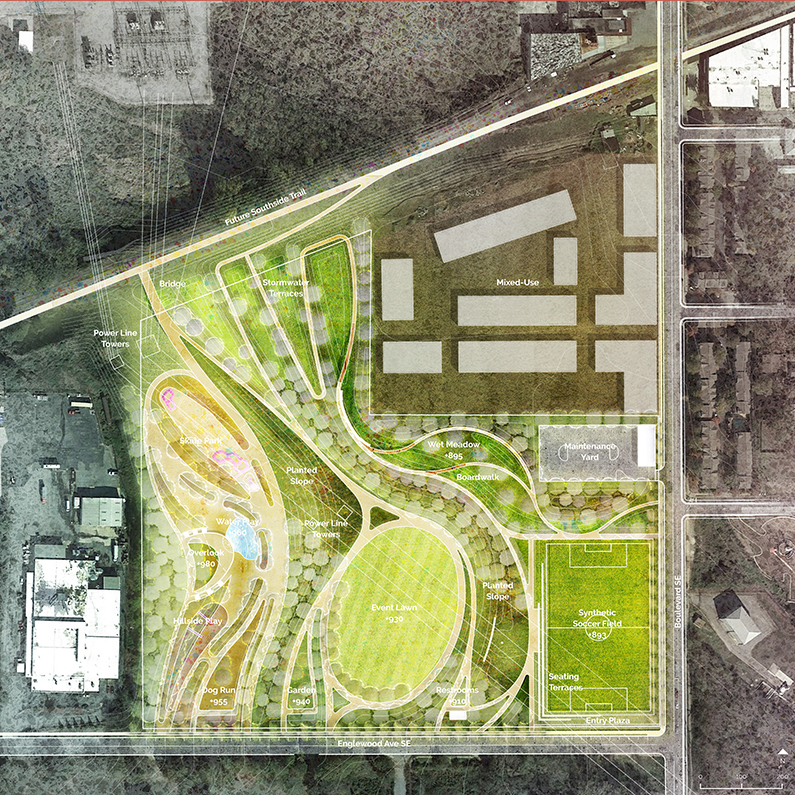

We’re going to find out because we will meet this 70 percent threshold for Boulevard Crossing Park, a 25-acre park in Atlanta that we are leading the planting design for in collaboration with design lead Agency Landscape and Planning. Over 70 percent of the landscape will feature Piedmont native plant communities, consisting of 52 tree species and 67 different shrubs, grasses and groundcover species. This diverse palette of plants will ensure a wide variety of food and habitat for wildlife and will be more resilient over time than a traditional park landscape. It will require less maintenance and less water in the long run. This is part of a holistic vision for the park that considers the needs of people and wildlife habitat as well as stormwater management.

The design choices we make can support the rich—and necessary—variety of the natural world. Plants can be more than just ornaments for our enjoyment. They can also be vital players in the web of life we are all part of.