Adrian Watson: Design in the Palimpsest City

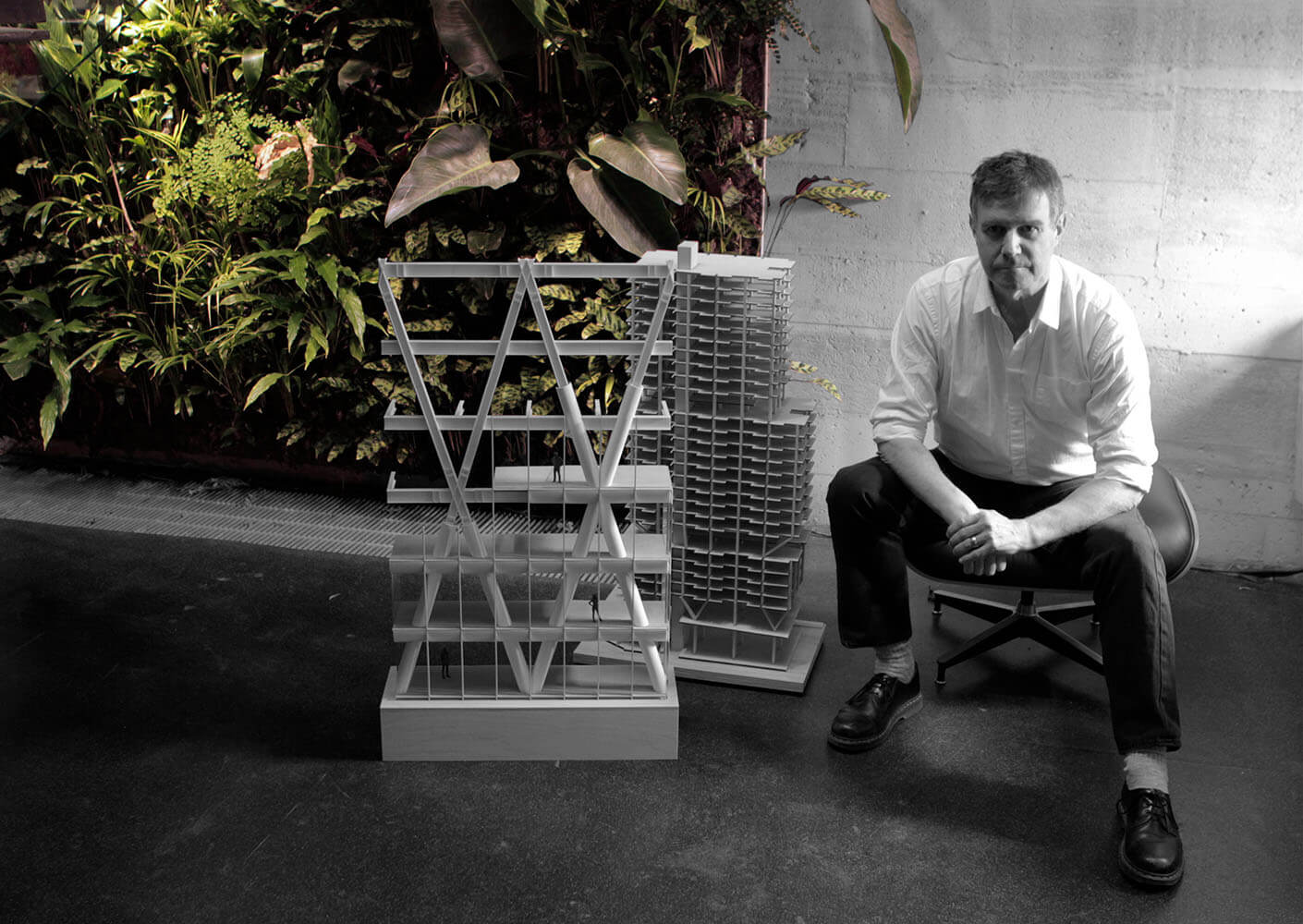

Every day, Adrian Watson, the design director of our Vancouver studio, arrives at work early. He relishes the quiet of the morning before everyone else shows up. It’s a time for him to reflect upon how fortunate he is to live in and design for this beautiful city.

Born in Vancouver but raised in the U.K., Adrian returned to his birthplace at two pivotal moments in his career. The first time was after graduating from university in the summer of 1987, when a friend introduced him to the work of the architect Peter Busby, whose firm, Busby & Associates, joined us in 2004. The second was eight years ago, when he joined the firm as design director.

Adrian approaches his design-leadership role with deep respect for Peter Busby’s legacy and great humility about the studio’s power to shape the city. His sensibility, much like that of his mentor, is philosophical: “Architecture is, for me, a branch of metaphysics,” he says.

Welcoming speculative design and thought experiments, he also endeavors to stay grounded. From the windows of the studio, which is on the 22nd floor of one of Arthur Erickson’s best buildings, the city is always in view, its gleaming towers girded by mountains, forests, and ocean—a constant reminder of the responsibility of the designer to serve humankind while caring for our fragile ecosystem.

Recently, Adrian answered some questions about his influences, his philosophical perspectives, and the studio’s part in shaping the future of Vancouver.

Peter worked with Norman Foster on the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank Corporation Headquarters building, which was the building that I admired and that was a great influence for me.

I am a Canadian even though my family left for the U.K. when I was a child. At the time I first came back in 1987, a lot of the work in this city was strongly influenced by American classical postmodernism—with one exception, and that was Peter’s studio. It was distinct and its influences resonated with me very strongly. The invitation to join the studio that had meant such a lot to me from a formative perspective was therefore quite remarkable.

“Less is more” or “Less is a bore”?

Less but better (Dieter Rams).

Page or screen?

Page (see answer 1).

Football or cricket?

Watching football, especially Nottingham Forest, and playing cricket (at least in my memory).

Pen or pencil?

I generally use an inexpensive Lamy Safari fountain pen with black ink.

Something that blew your mind recently?

Mitsugi Saotome.

I’ve been here for eight years now, and my role is really designing the studio process as much as designing architectural works.

There are one or two projects where I am the design leader, but for me the most important aspect of anything that we’re doing is recognizing that architecture is a collective challenge. I am very conscious of the ambitions of others, that they are creative thinkers first and foremost, and it is important that everyone feels attachment to and authorship of their work, from the most junior person to the principal, that it is work that they are deeply embedded in and committed to.

Architecture is something that takes a relatively long time to realize. There is a lot of personal commitment and time invested in the work, and I think it is vital that we all feel that connection and ownership of the work.

Our old studio was in Yaletown, very much a postindustrial zone of the city. It was pretty sketchy as I remember it from the 80s. I think even when the studio established itself there, it was on the outskirts of where you would locate an office or an architecture studio. I think our studio has always had a pioneering spirit in this regard.

But now we are much more in the Central Business District—in a building that I still think of as the MacMillan Bloedel building. From my perspective, it’s Arthur Erickson’s best building. It’s one that I always admired, and so finding our home there is fantastic.

A new environment has given us a great opportunity to take a breath and look at things with a fresh eye. The move provided an opportunity to apply our values around reuse of materials and disassembly. We were serious about reusing a lot of the material, not just simply furniture, but taking apart the things that we had built in our previous studio and repurposing them in our new home.

There was a thought experiment that I played mischievously here in the studio. I asked the studio to try to define what architecture is—because it’s a term we use every day. And then I asked everyone to visualise the building we were in and to incrementally remove elements from the building until it no longer registered as architecture.

I was inspired by an image of Louis Kahn’s Trenton Bath House, which was at the time in severe dilapidation. So in the thought experiment I was asking, “as you pare the building down, at what point does it no longer resonate with you as a piece of architecture?”

For me, the answer to this question, lays within the formal, numerical relationships of the structural elements of the building. This is the aspect that I consider to be essential to the understanding of architecture. If you consider Stonehenge, it had an architectonic function which was to represent its builders’ understanding of their own self-image through its purposeful creation. To me, that’s the ontological truth of architecture, which works beyond all the other practical, aesthetic, sociological and environmental concerns. Our built forms become mediators between us and things which are unknown. That’s what I mean when I say we build to know.

Gestalt is the way we choose to work amongst ourselves in the studio, how we work collaboratively. For me, one of the most important functions of the studio is to hold space for individuals to find self-fulfillment. Gestalt is the balance between personal drivers towards fulfillment and that energy being harnessed to collective ends. From my perspective this is the appropriate definition of my role as design director.

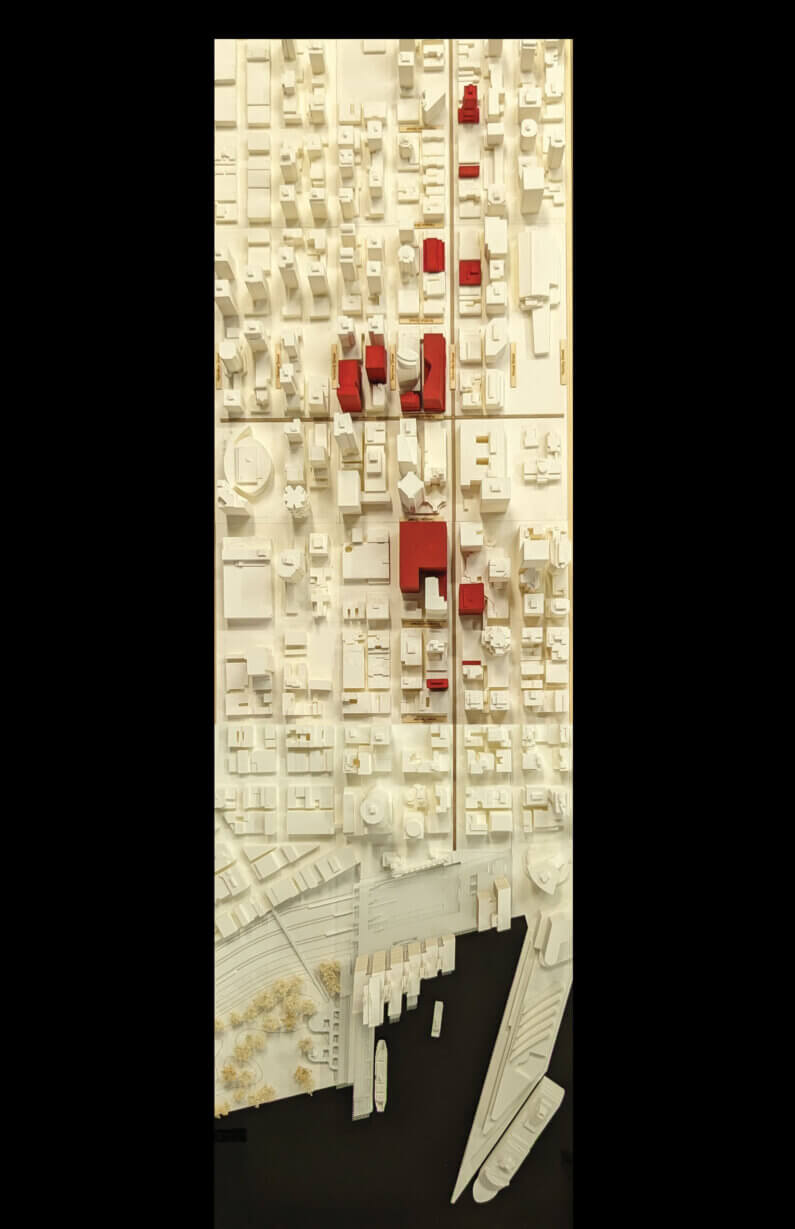

This studio is in a privileged position to be engaged in several projects where we are working directly with First Nations groups, and we are all starting to appreciate how little we understand in respect to the precolonial narrative of the city. That’s why I use the term “palimpsest” to describe Vancouver. There is modern Vancouver—that which we can see in built form—but understanding what underlies that is key for the image of the city as we look to the future.

Now, recognition tends to be very tokenistic. It’s at the level of the icon rather than an understanding of underlying and fundamental value systems that should form part of the self-image of the city. That’s not just a challenge for me or for the studio. It’s a challenge for everyone who is part of this wider community.

Yes, that’s exactly the case. I think we need to find ways to move beyond decorative application of motif, although symbolism is important, and to be more inquisitive at a deeper level. And the storytelling aspect of that is something that I think is absolutely the critical first step.

But how does that translate into a sincere engagement? These are unceded territories, so this is not actually an issue of just recognizing a past. This is about a living heritage, ownership, and stewardship of the land that we have been privileged to be able to find our place and our home within.

As a designer, how do I unlearn to be able to have a sincere dialogue with those who have a very different cultural perspective from the one I have inherited?

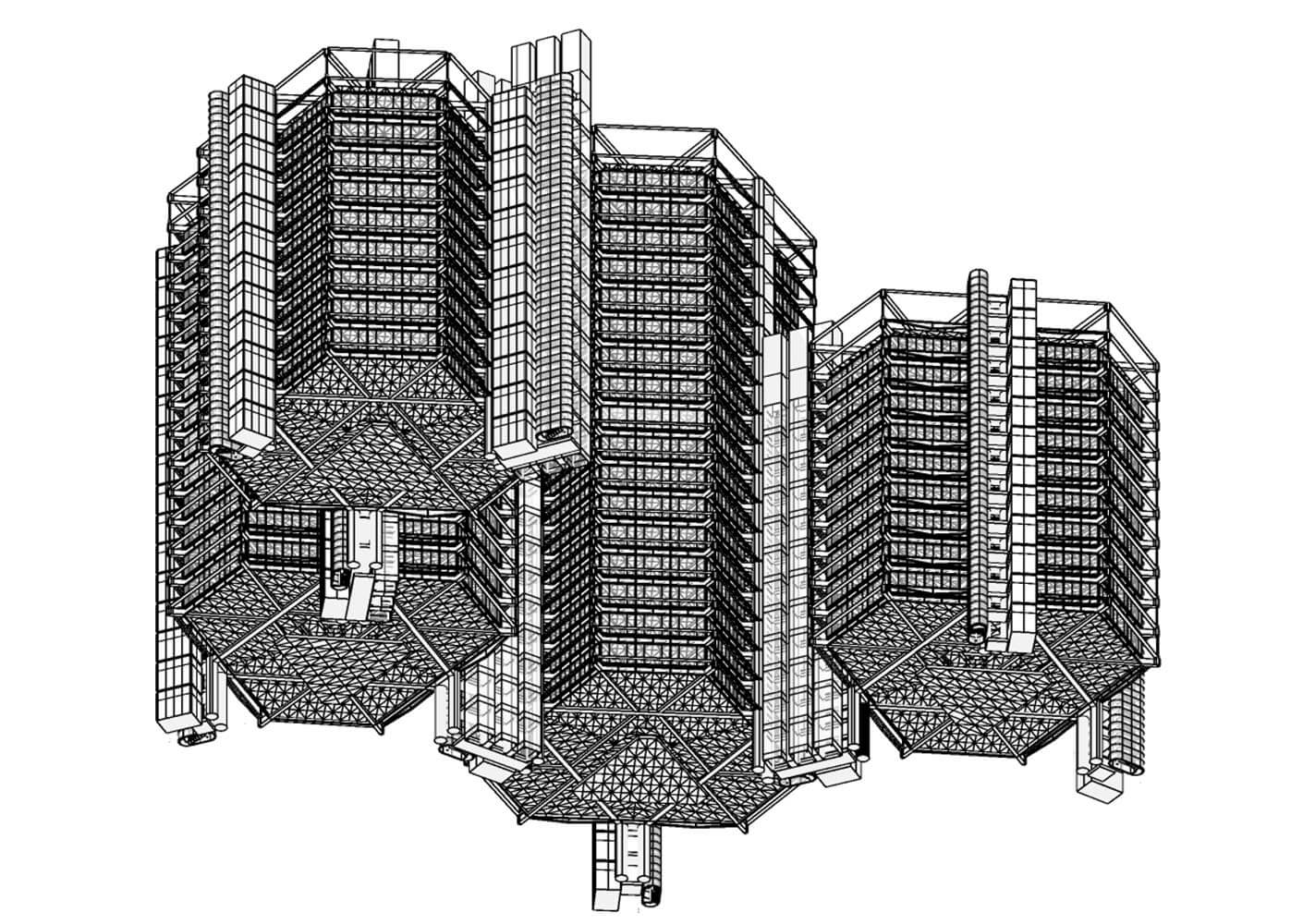

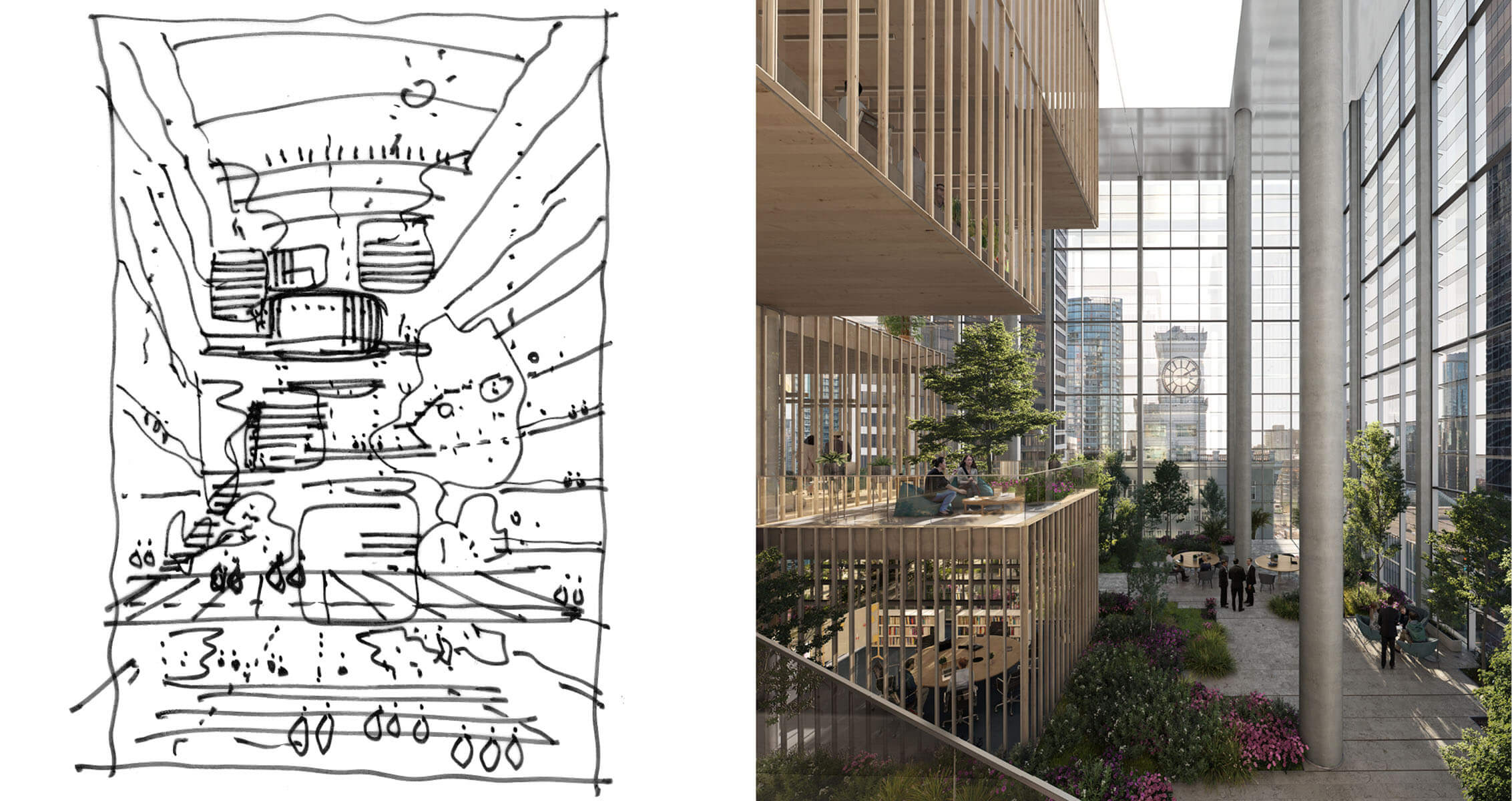

It’s still a challenge for us to come to grips with what this story means to us. We’ve been incredibly fortunate over the last few years to have been entrusted with significant projects in the heart of the downtown core. Understanding those projects not so much as individual pieces but as a suite gives us an opportunity to ask ourselves questions about our role in shaping the image of the city.

We see cities where activity is denuded from the core. Conservation and enhancement of the social functions, particularly entertainment and retail as well as the introduction of more diverse commercial uses, is fundamental to the longevity of the downtown as the vital heart of the city.

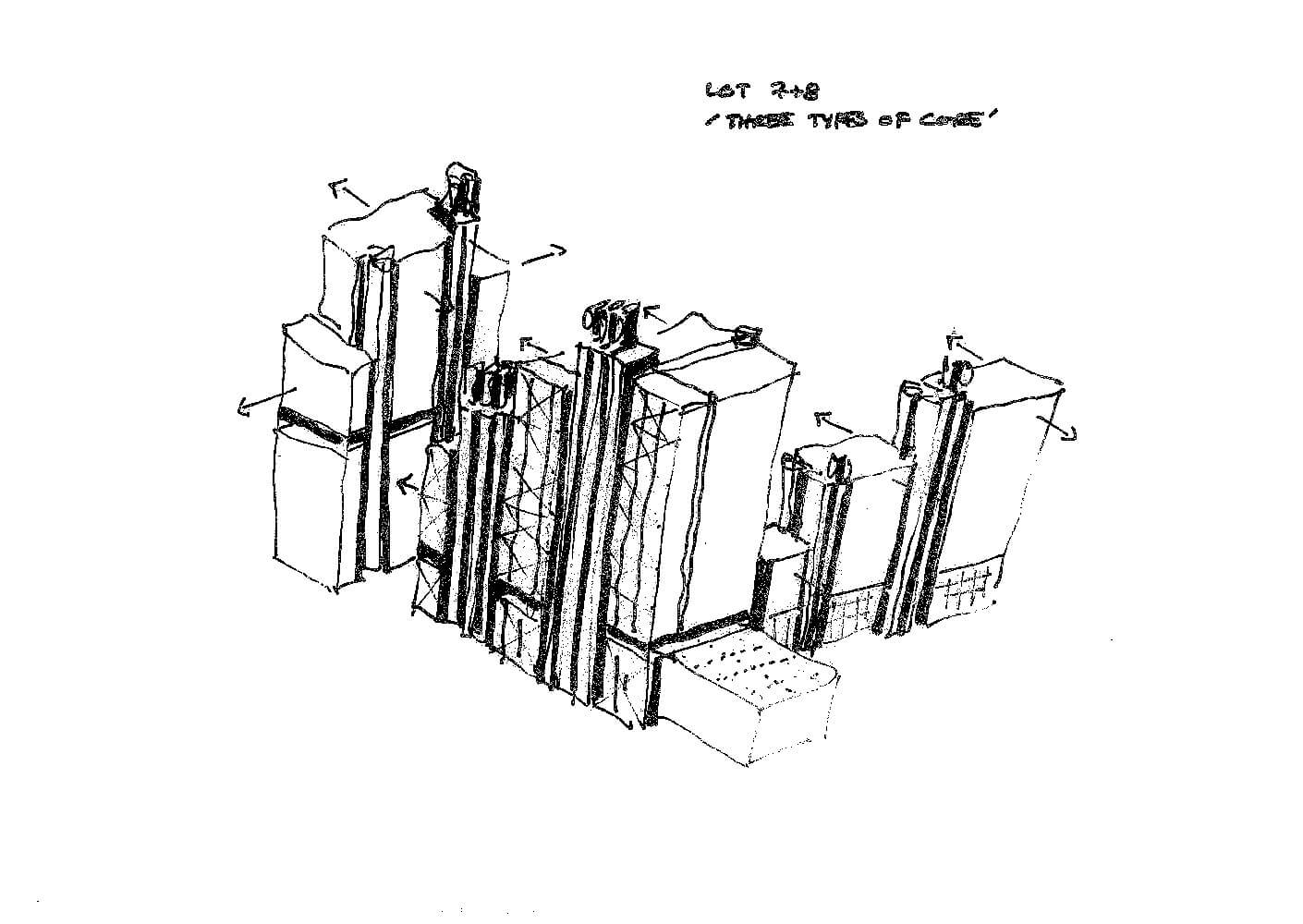

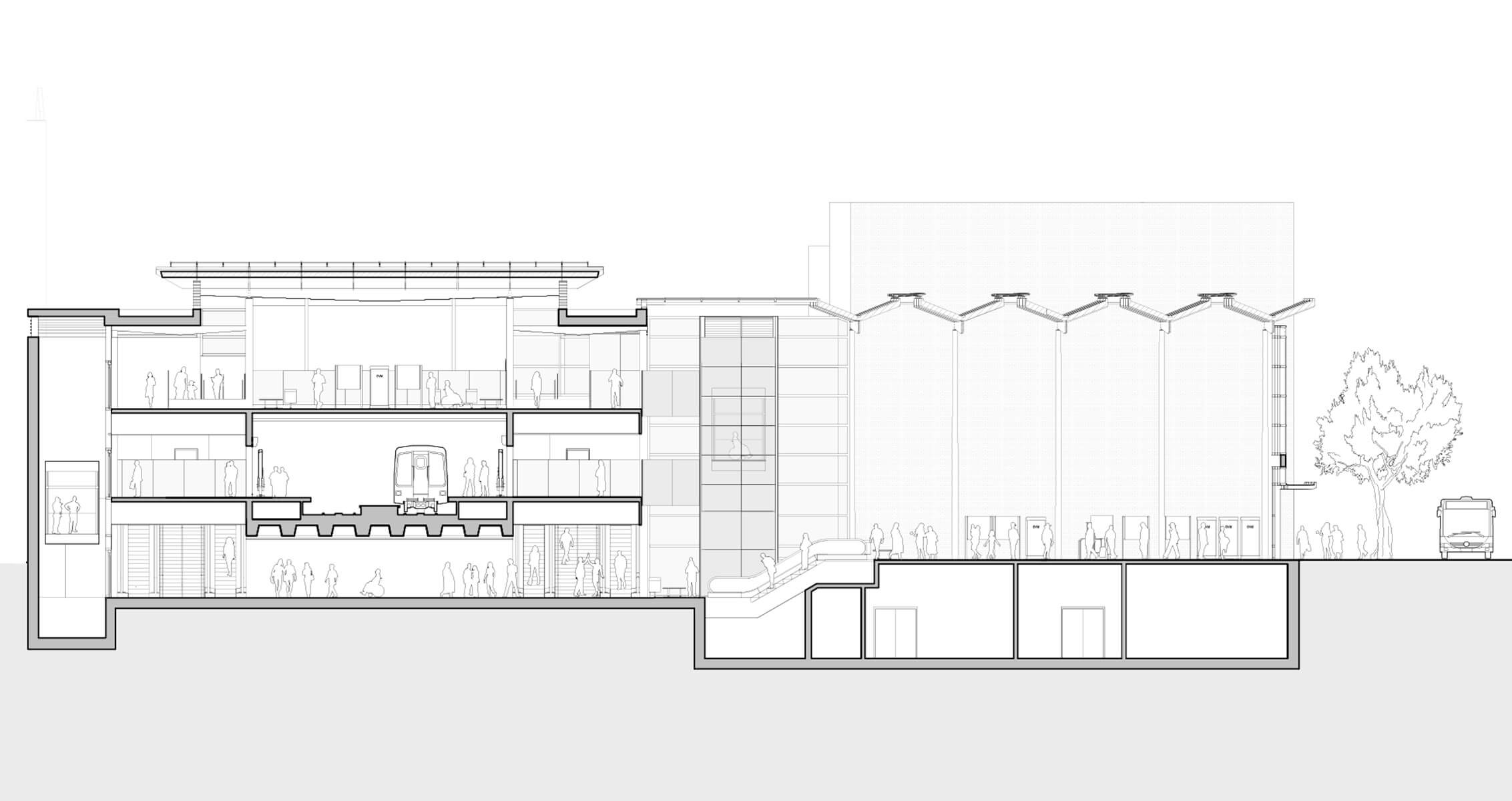

Waterfront Station is a speculative project that came out of research we were doing three or four years ago around the subject of super-modality and the integration of transit infrastructure into the city.

It started as a very small study we shared with a few people, but then took on a life of its own! There was some interest, and then it ballooned and has proven to be a catalyst to engage people in thinking about this location. I feel we have given an indication of how with a little bit of courage it is possible to step beyond the obstacles and impediments that prevent us from looking at this precinct with vision.

Well, definitely our clients. The people that we work with share the same objectives we have at a very high level. Ultimately, we’re working towards objectives that improve the spaces in which we live, that improve transportation connections, to be agents of positive change.

And then the other partner is the city. I think we’re very much in sync with the ambitions of a very progressive city in respect to environmental performance goals. Embodied carbon is the next big challenge for us, and the city’s objectives are in complete alignment with what we have been advocating, as a studio, for 40 years.

Finally, I would argue, that all of us, as citizens, are our most important constituents. We always strive to be sincere and honest, and we share our work with the attitude of open arms, and open hands. That’s our gesture to everyone. We want to put our energy and creativity to effect change in the city and in a way that is an expression of love.