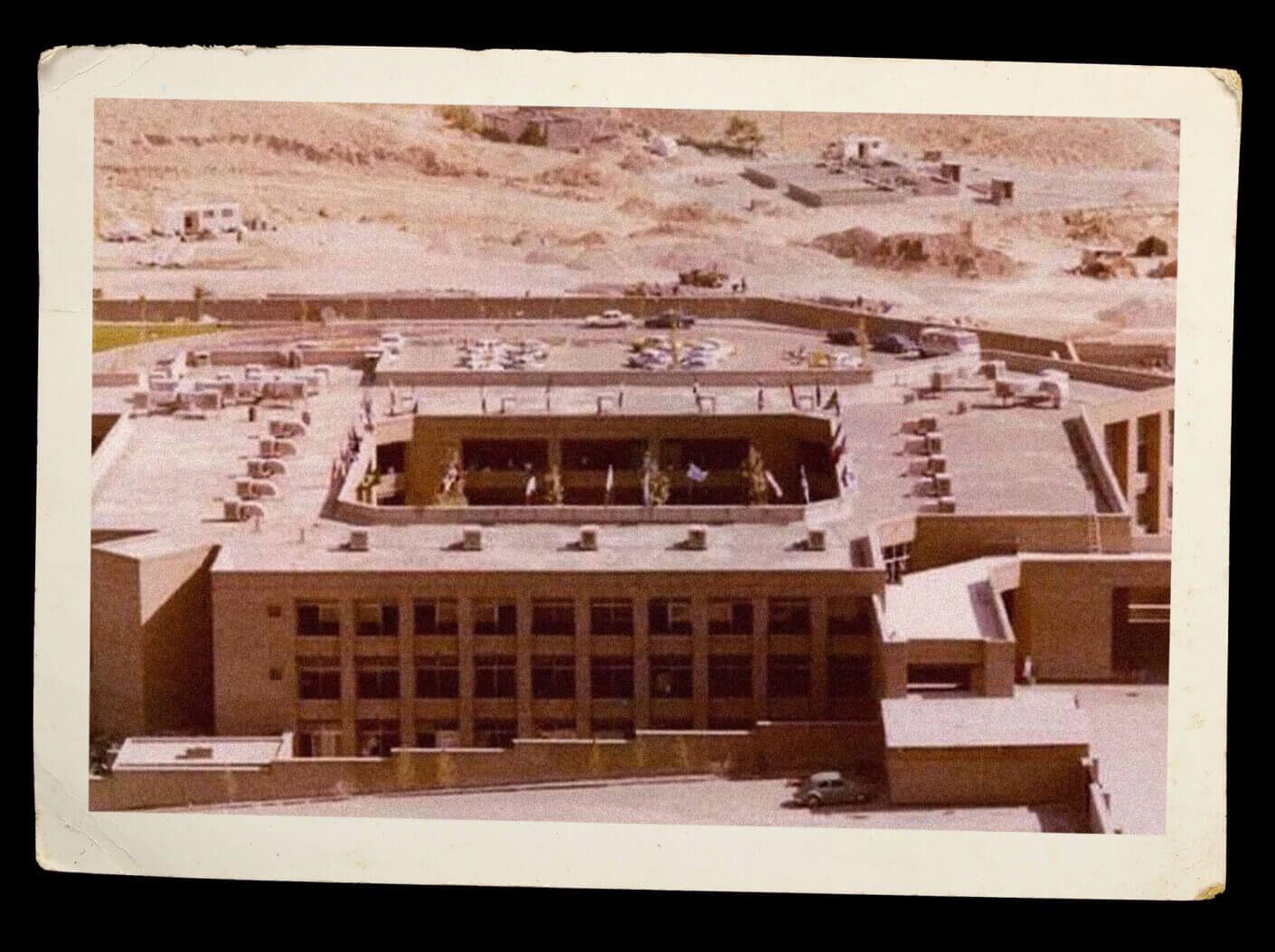

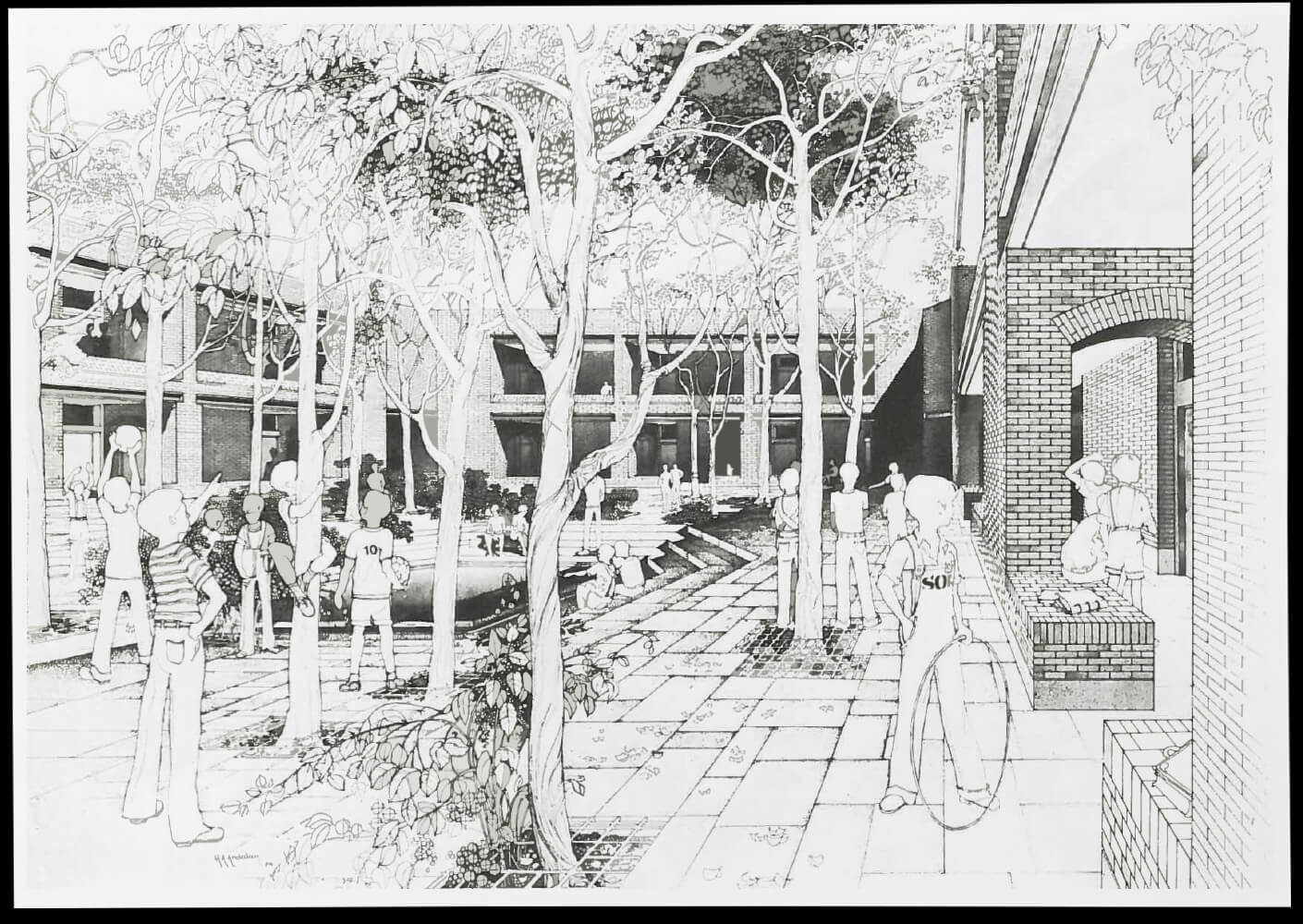

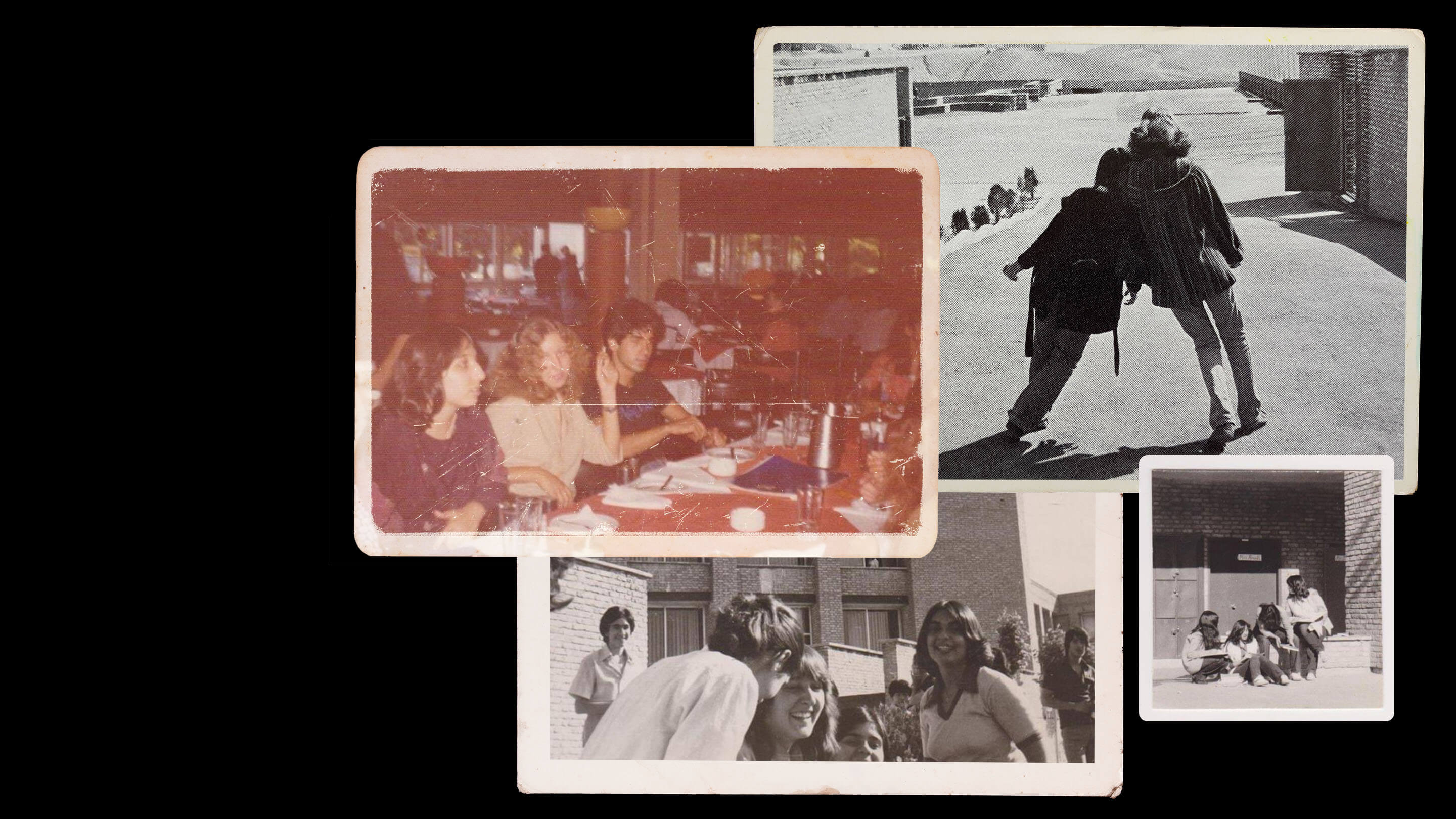

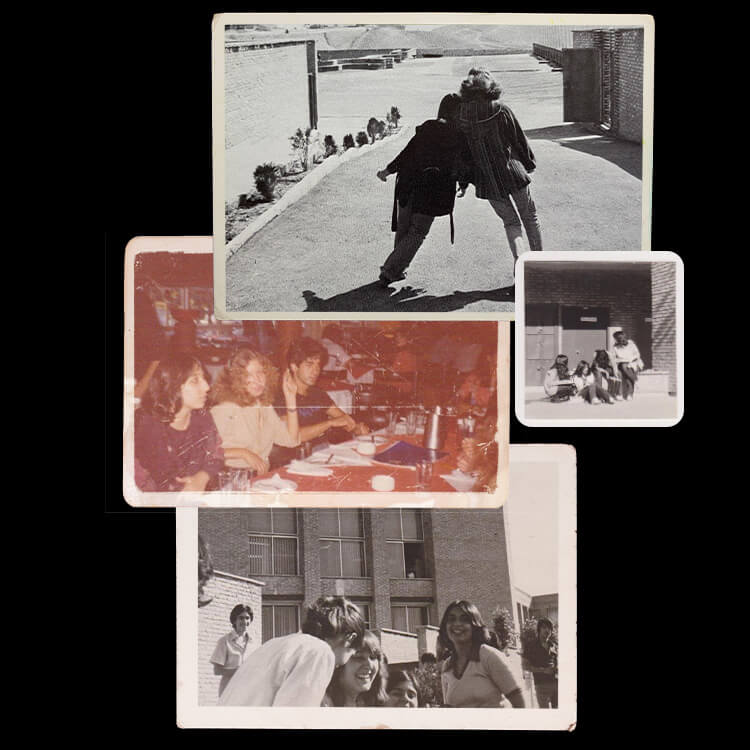

Initially, the private school occupied a large residential compound in downtown Tehran. It hosted grades K-12, with 326 co-ed students and 40 teachers. The most iconic landmark was the grand exterior circular stairs, which became the spot “to see and be seen.” This is where upper-class students flaunted their seniority, young couples sat together, and students played guitar. It was filled with playful laughter.

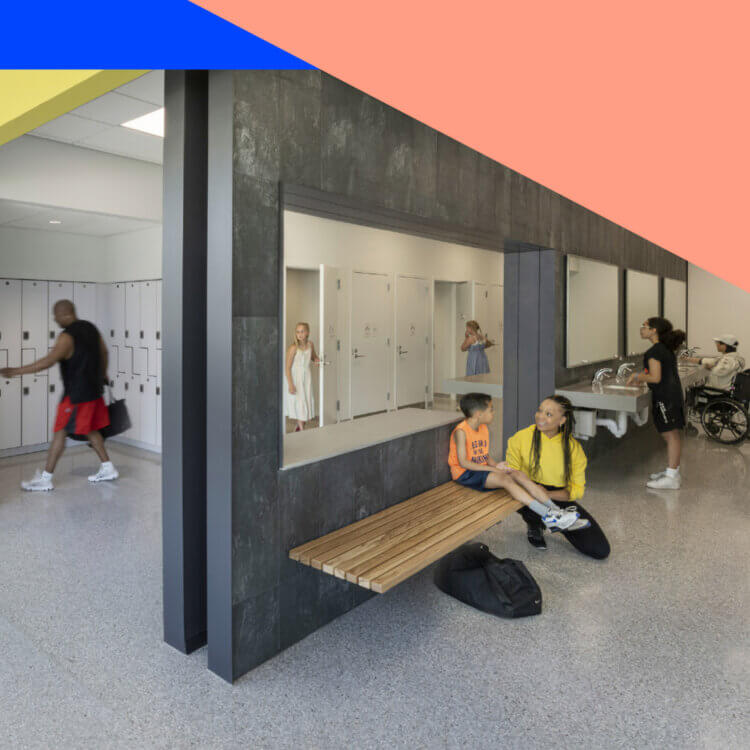

In 1971, I began attending Iranzamin as a 4th grader. I watched the older students with awe and soaked in the atmosphere. The western vibe lasted into the mid-1970s, with students wearing the latest American and European fashions. We celebrated both Persian Nowruz (New Year) and Christmas festivities. Iranzamin created an environment where students could thrive with personalized attention, knowing each family, intentionally hiring international teachers, and accepting students from all backgrounds.

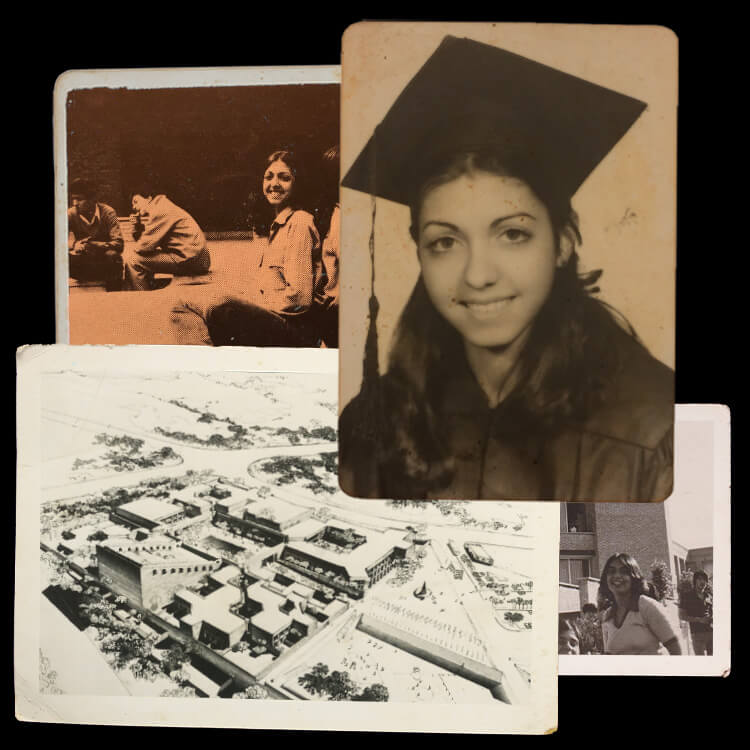

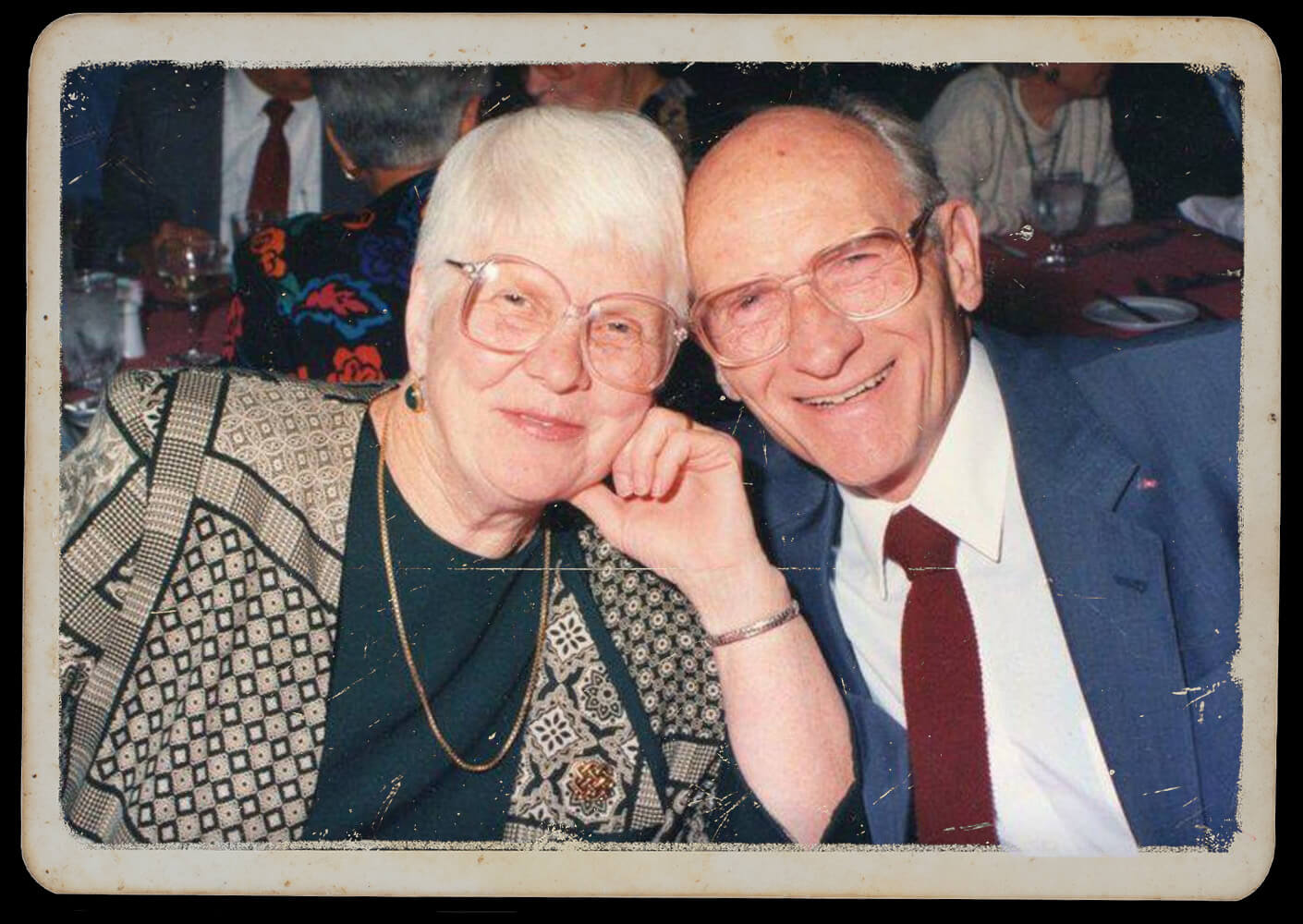

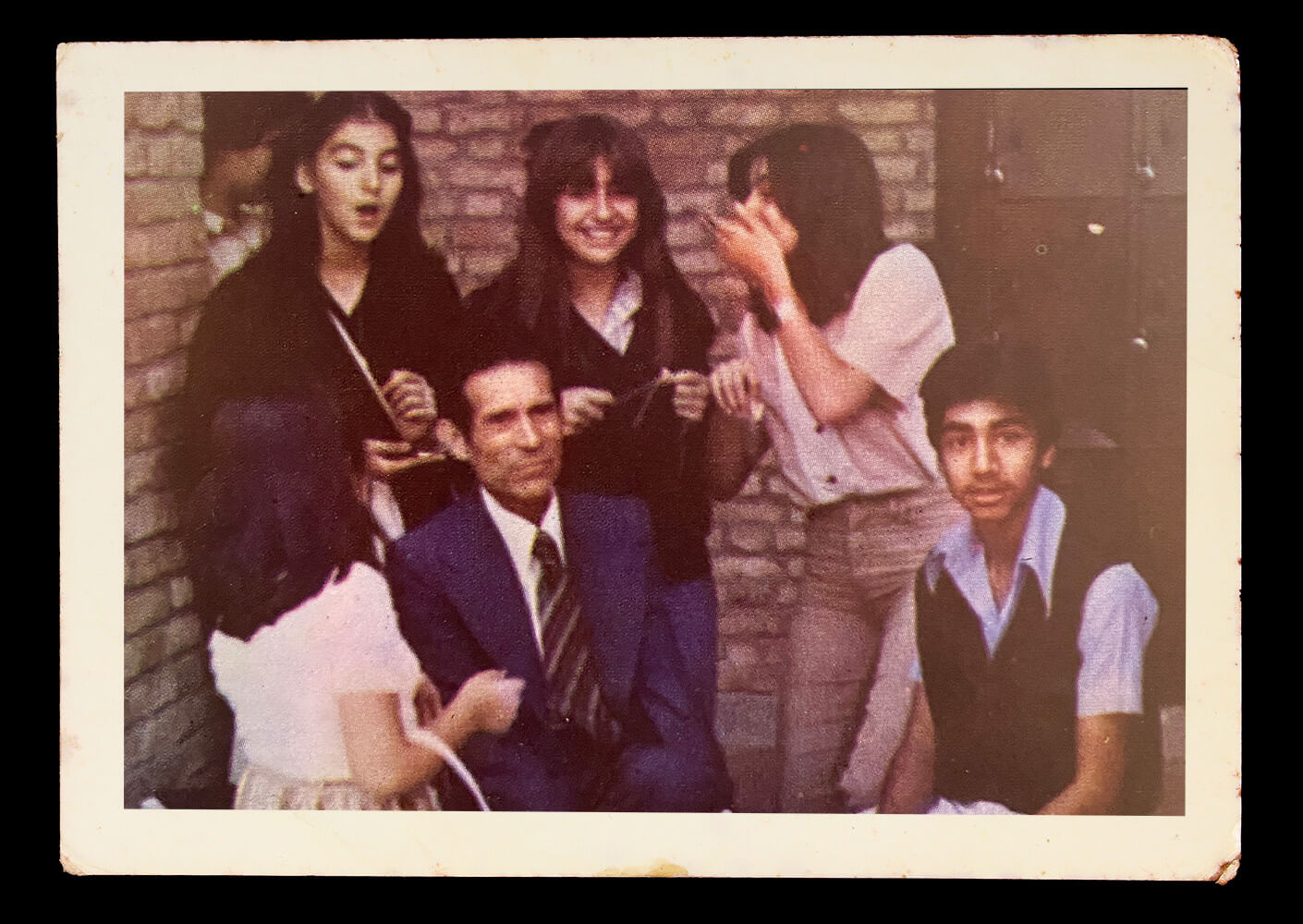

This is why I felt a strong sense of belonging at Iranzamin. Compared to other Iranians, my family was westernized. My maternal grandfather was from Iran. He married an American, my maternal grandmother, in New York, forever altering the trajectory of our family history. My mother, Laleh Bakhtiar, and Iranian father Nader Ardalan, were born in Tehran, raised in the U.S., and met in Pennsylvania during college. After marriage, they both went to graduate school, then moved to San Francisco, where I was born, followed by my sister Iran Davar.

Dad became an architect and mom a scholar before they moved back to Iran to discover their roots. There, my brother Karim was born. Our parents traveled with us throughout Iran’s countryside, documenting the architecture. In 1973, they co-wrote The Sense of Unity: The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture—a pivotal book which guided the design approach for Iranian architects at the time. At home, we spoke in English, watched American TV, listened to DJ Ted Anthony on the American radio station, and played American records, all while learning about Persian culture.