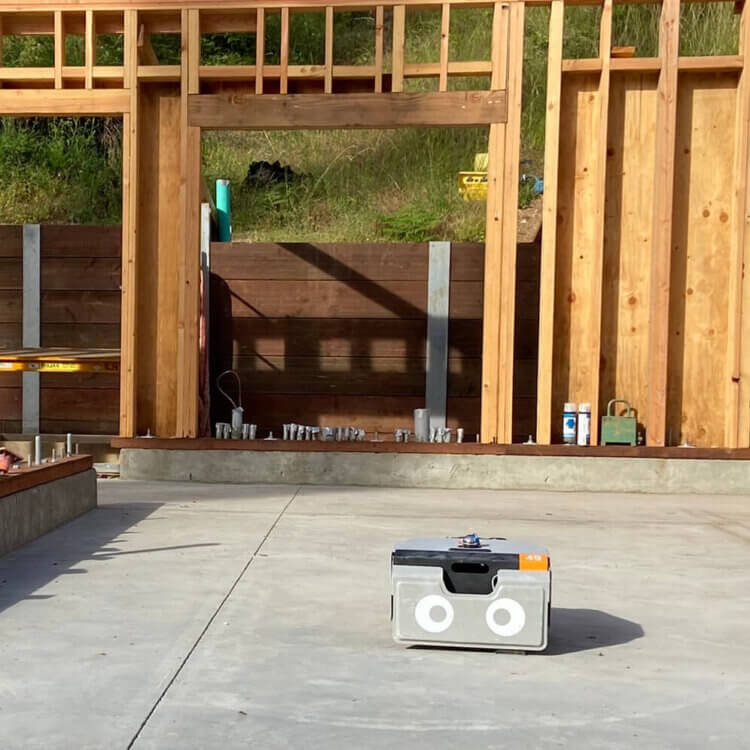

When architects began designing the new Morrow High School in Atlanta, Georgia, they didn’t only consult teachers, administrators, and other stakeholders. They also referred to public health data, which showed that the surrounding community had a high rate of obesity. To address this issue, they created an S-shaped building with prominent stairways that encourage students to take more steps throughout the day. The school, which opened in the fall 2022, embodies an active design.

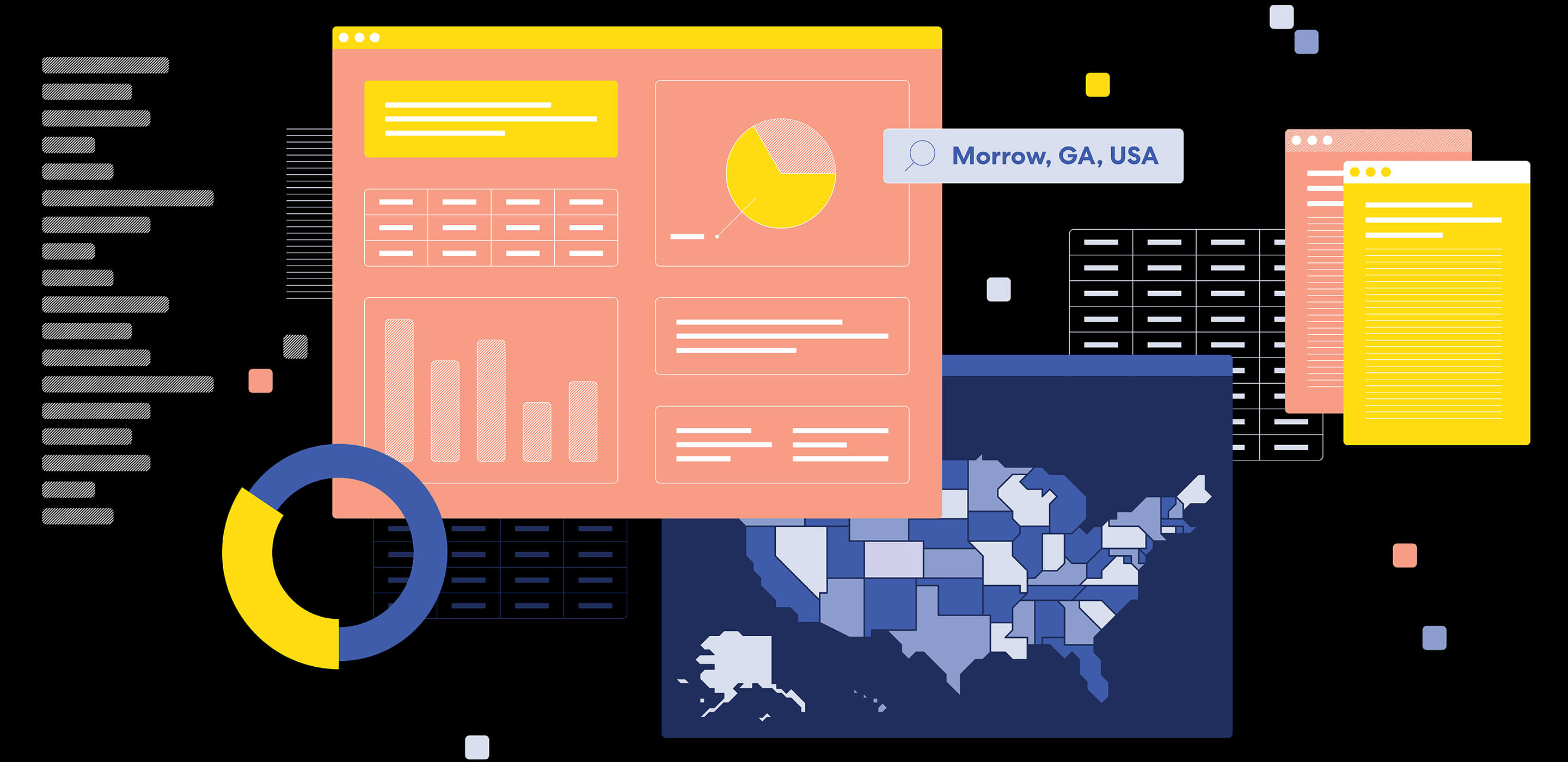

Not every designer has the resources to mine and analyze public health data. But now, a team of researchers and public health experts has brought the power of big data—from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and other organizations—to designers throughout the country. They created PRECEDE, which stands for Public Repository to Engage Community & Enhance Design Equity, with the help of $30,000 in seed funding from the American Society of Interior Designers (ASID) Foundation. Free and easy for designers to use, the PRECEDE dashboard and website identify the top public health concerns for a given project site, along with educational public health materials and design strategies for improving those outcomes.