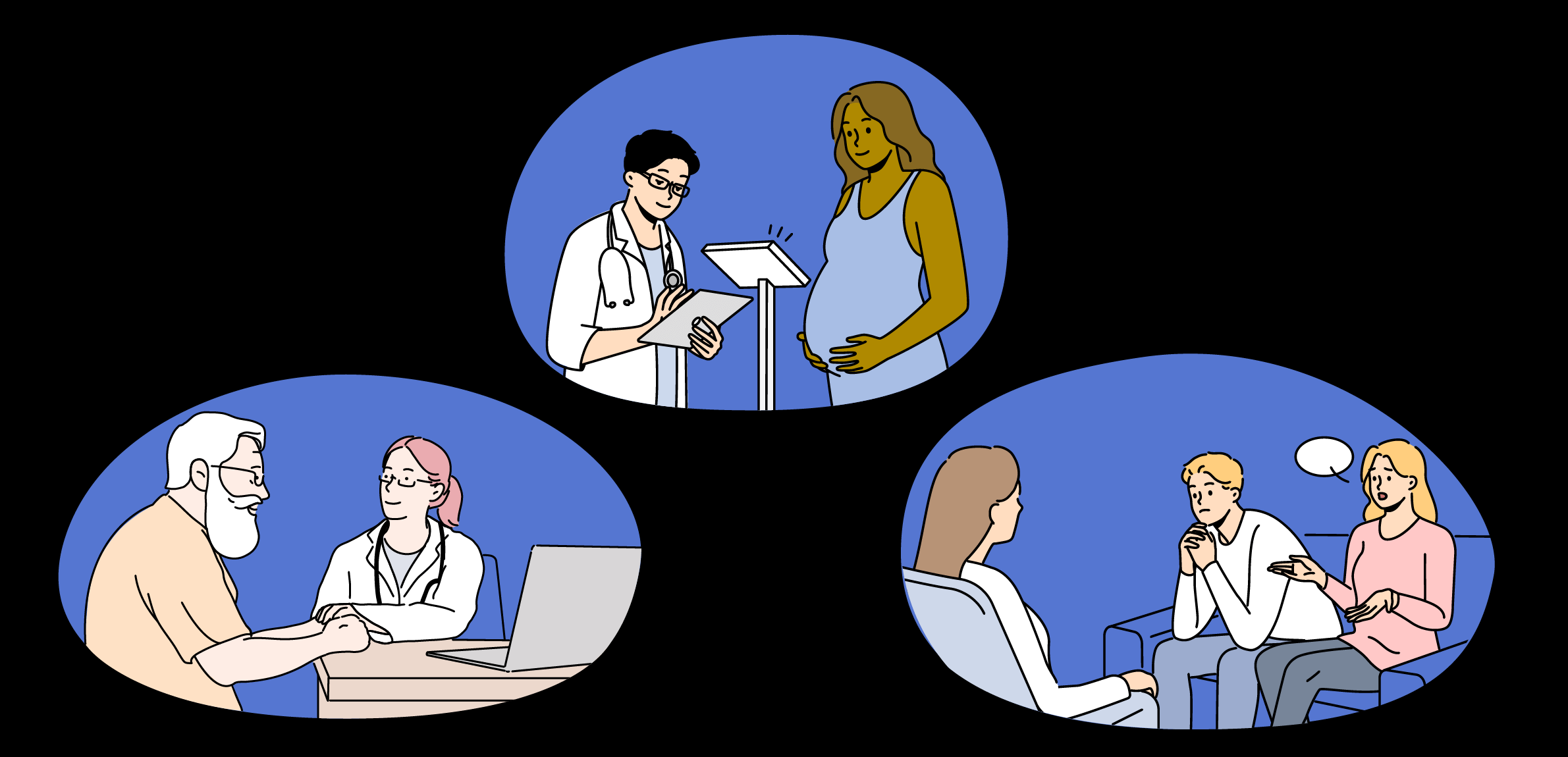

Olivia, a 23-year-old resident of suburban Kansas City, visits her local public health clinic for a prenatal exam and immunization update. When her nurse observes that she is underweight, Olivia says she can’t always afford groceries and is feeling depressed and anxious. These issues are beyond the nurse’s expertise, so she walks Olivia to the mental health clinic and helps her get an intake assessment with a licensed mental health clinician. She also asks a case manager to help Olivia sign up for food assistance.

Thomas is a 72-year-old recent widower who is deeply saddened by his wife’s death. He visits the health services building to talk with a psychologist, and he mentions during their conversation that he’s having difficulties with Medicaid enrollment. The psychologist introduces him to a case manager who explains his Medicaid benefits and, when Thomas says he’s struggling to cook for himself, signs him up for free meals through the Aging and Human Services program.

James is a 56-year-old veteran who was diagnosed with PTSD following his military service in Desert Storm. News coverage of a mass shooting last weekend induced flashbacks and nightmares, and he went to a bar and relapsed after being alcohol-free for 10 years. His wife has brought him to the counseling center for help. She expresses concern that James has also started taking narcotics, so the counselor refers him to the on-site drug treatment program for a same-day consultation.