Los Angeles County is home to the largest unsheltered homeless population in the United States. The largest concentration of that population lives a few blocks from Perkins&Will’s studio in Downtown Los Angeles. The struggle of the man sleeping on the bus stop at one end of our block and the woman asking for change at the other is just part of our daily lives. In 2017, our studio decided to become part of the solution to the crisis in our city, and that decision has led our design practice to experiment with exciting and inspiring new expressions of our firm’s social purpose.

There was a moment, though, when we almost decided not to go down this road, when we almost decided not to rise to our mandate as designers. And that story—the story of how we turned the philanthropic mindset our studio has always had into an integral dimension of the work we do—started with a plan.

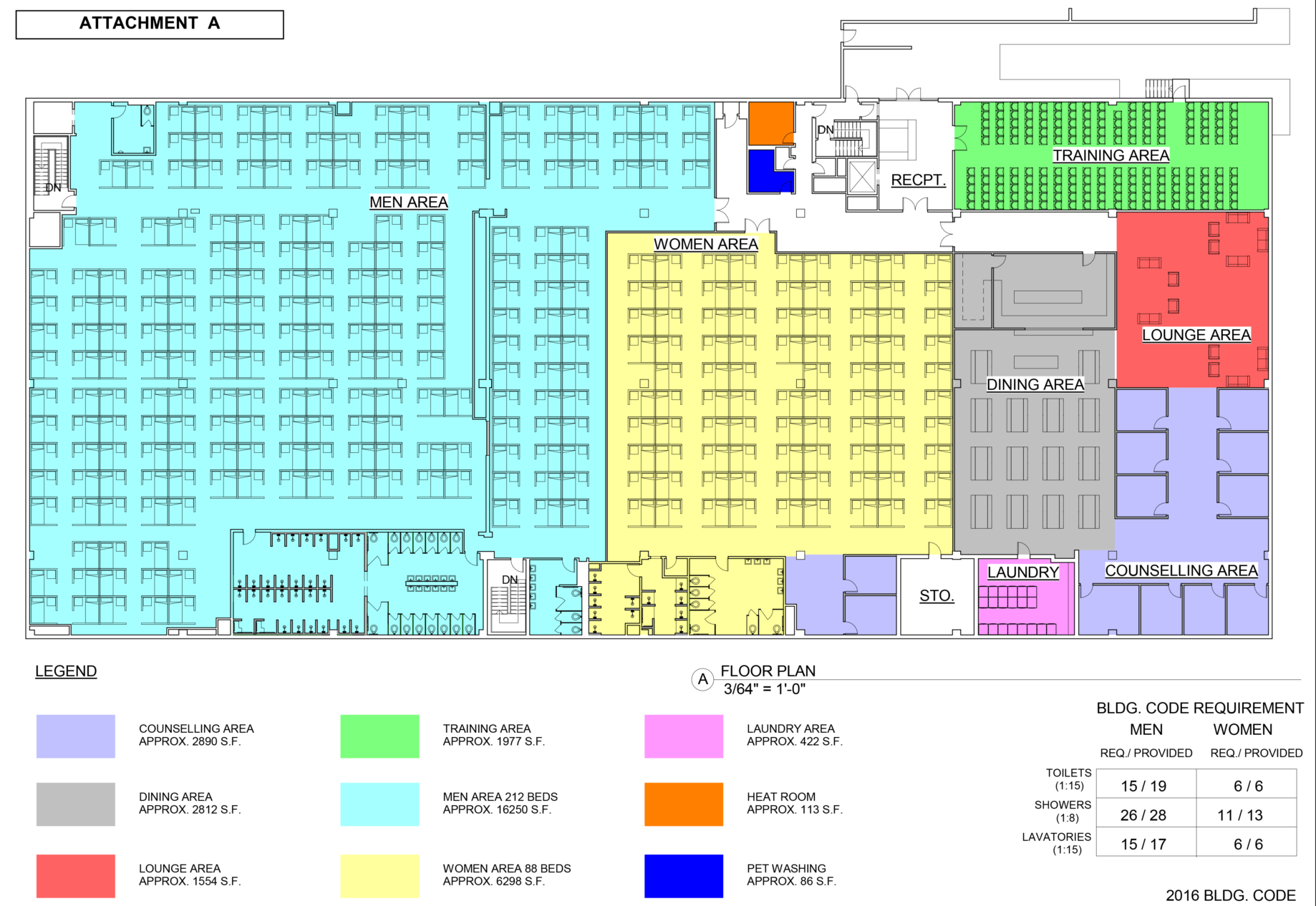

More precisely, it started with this plan: