We’re excited to welcome Mike Bryan, MLA ’26, as this year’s Phil Freelon Fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD).

We established the Phil Freelon Fellowship Fund in 2016 to increase diversity in the field of architecture by providing financial support and expanded academic opportunities to underrepresented students in the design profession. The Fund’s namesake, Phil Freelon, was the design director of our North Carolina practice and a frequent mentor to students at the GSD.

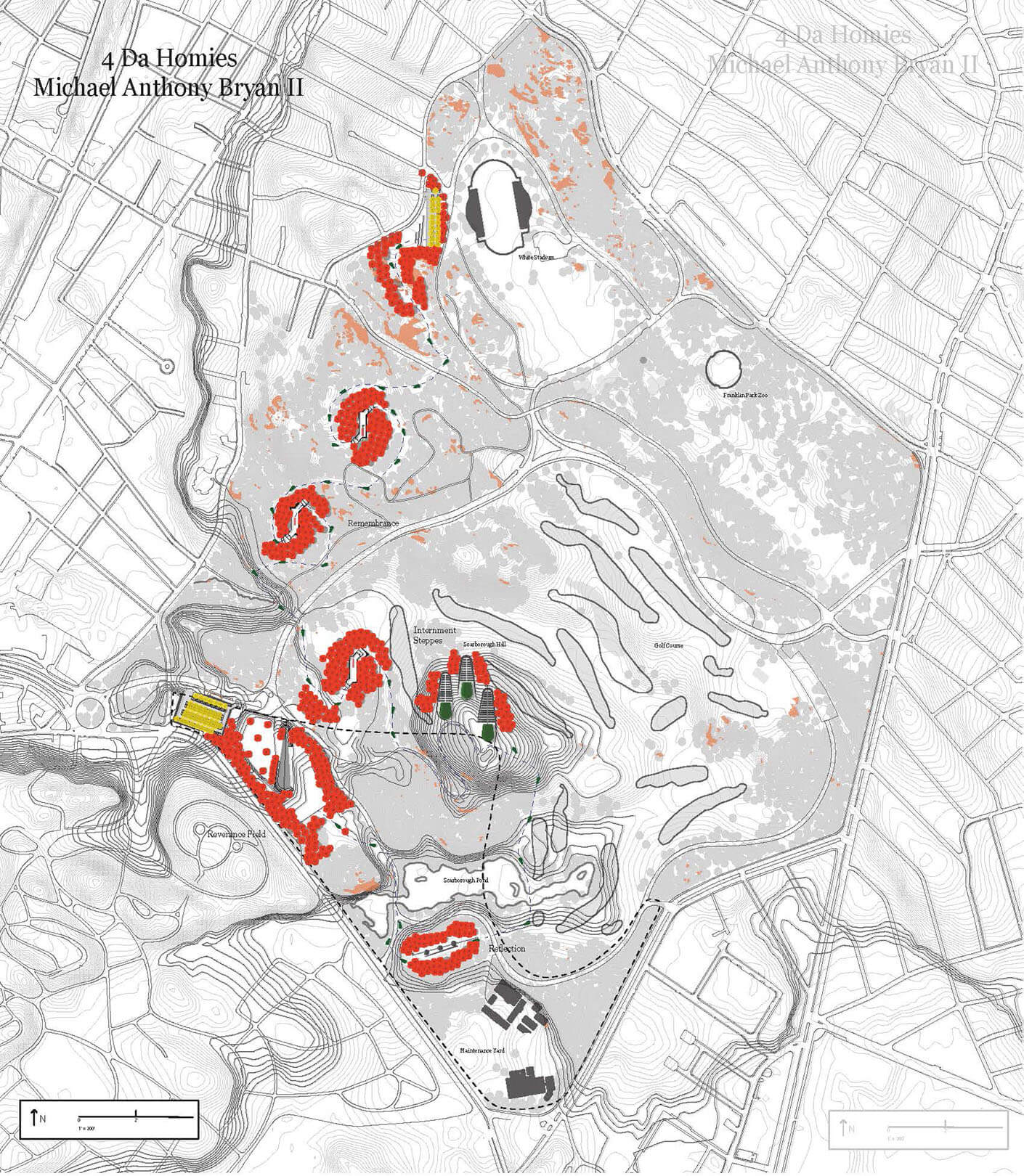

Now in his second year at Harvard, we sat down with Mike to discuss his explorations in landscape architecture and how it can evolve into a powerful tool for environmental remediation, social justice, and cultural memorial.