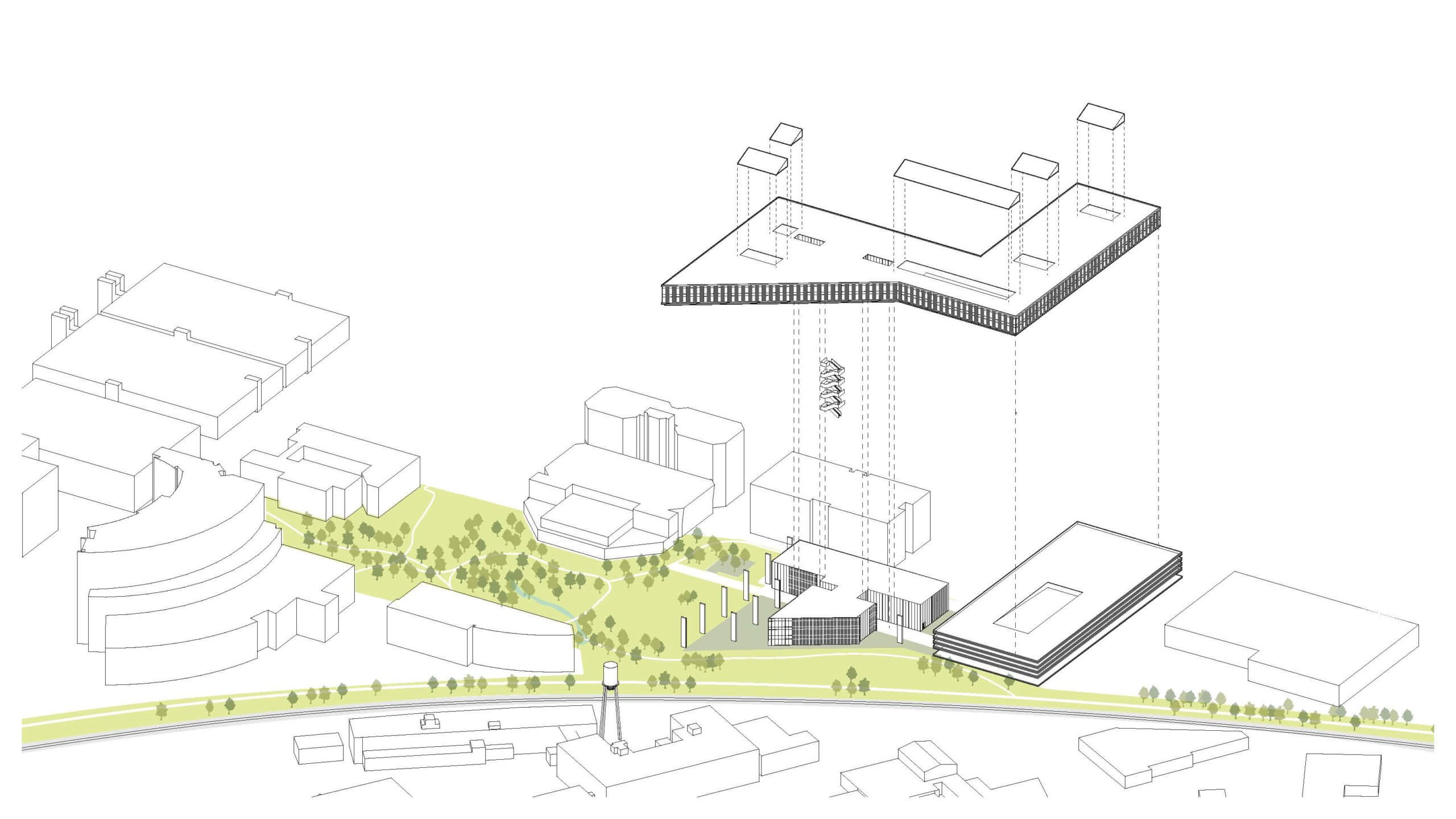

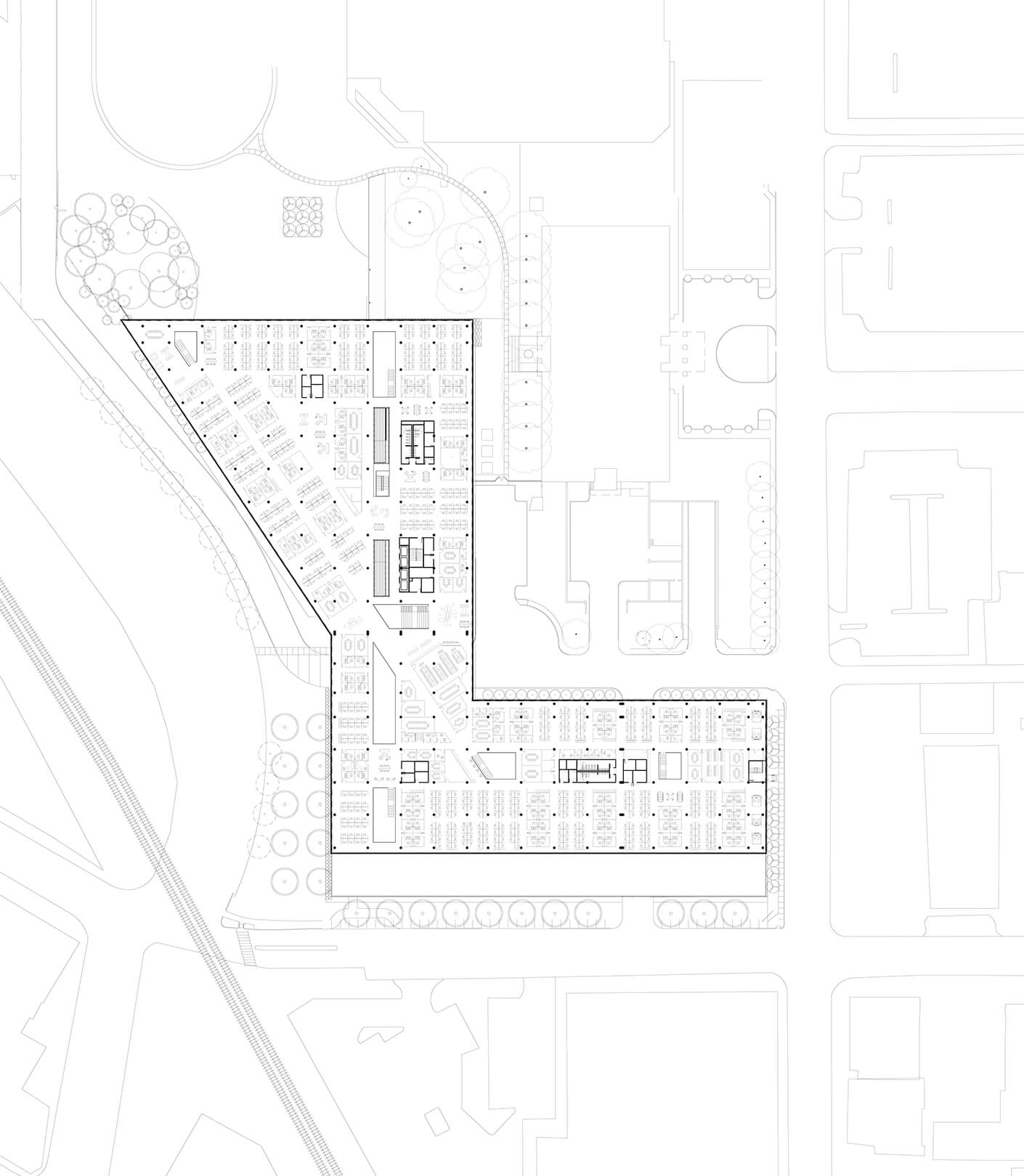

Groundscrapers are defined as buildings that are as wide as skyscrapers are tall. The typology has its origins in the industrial architecture of the early 20th century. Fine examples of these monoliths still exist in Chicago, such as the U.S. Post Office (1932) or the Merchandise Mart, (1930). These buildings hug the Chicago River for as long as they possibly can, a design choice fueled by the desire for waterfront real estate. But in more recent years, Big Tech companies like Apple and Google have also harnessed horizontal forms as their calling card; the “campus feel” of their headquarters stems from the connectivity of the ground-hugging structures, clustered to create a shared and vibrant streetscape.

Cities with room to grow outward, like Dallas, home to design director Ron Stelmarski, are at the forefront of this trend toward connectivity as workplaces adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic. By alleviating the need for a cramped elevator ride, groundscrapers keep people appropriately distanced, as well as more active. They also break down outdated hierarchical systems, placing teams side-by-side to eliminate the elitism of the penthouse.