Studies have shown that a diverse medical workforce leads to better health outcomes. “There’s a huge push right now to train health professionals who look like and talk like and culturally understand the patient population they’re going to serve,” says health education design leader Heidi Costello.

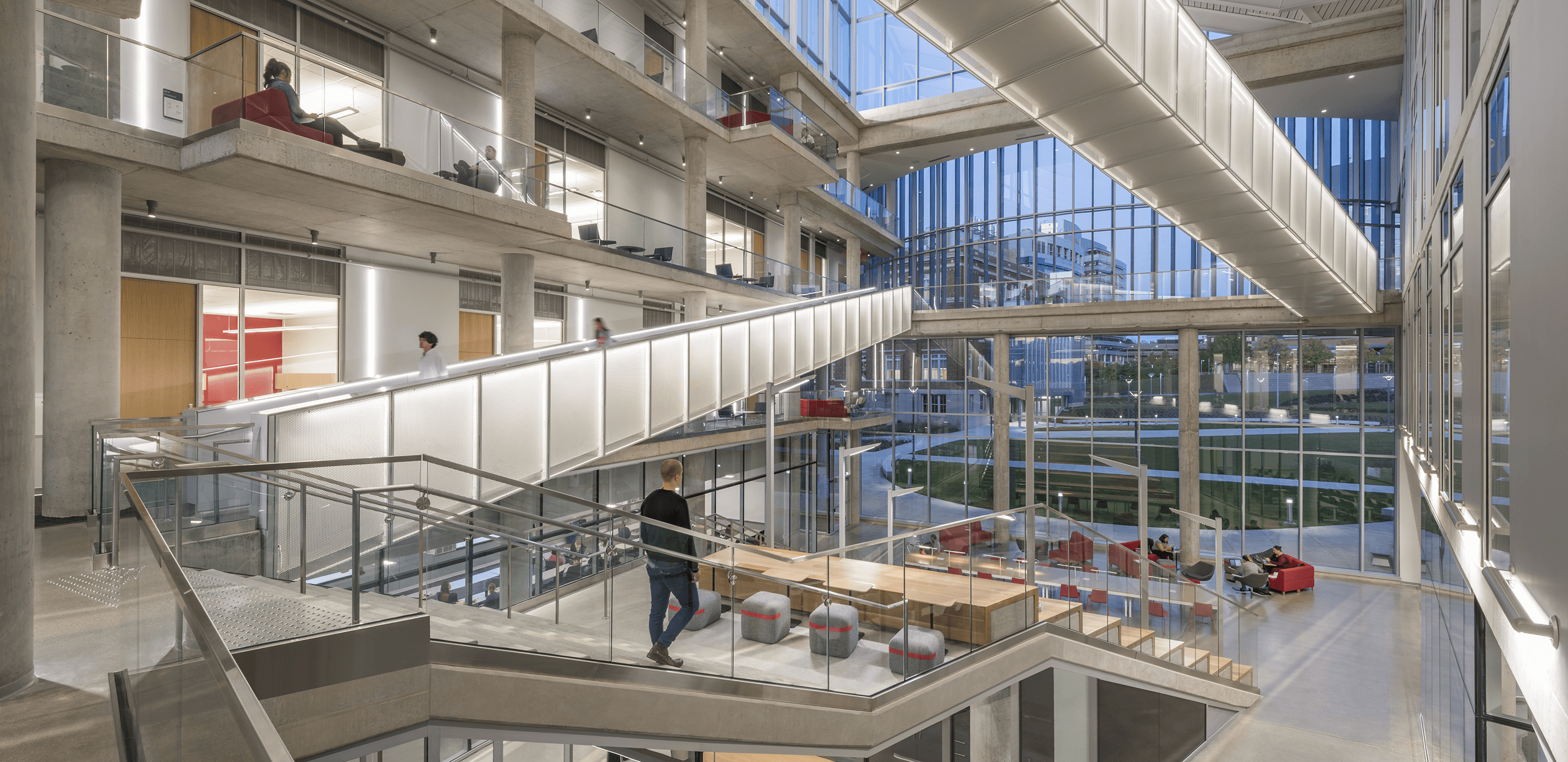

Colleges and universities hoping to meet the needs of communities where their graduates will practice medicine are putting diversity front and center. Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine took this challenge quite literally, in fact. Early in the design process for its new building, students on the college’s anti-racism curriculum committee advocated for a physical manifestation of equity and inclusion efforts.

“We met them, and they said they wanted a presence in the new building,” says architect and designer Jerry Johnson. “And they didn’t want to be tucked away in the back or on a top floor. They wanted to be up front; they wanted a space that was open and welcoming right away.”

With the support of the administration, Johnson, Costello, and their team delivered just that. “We located our Office of Inclusion in the atrium, one of the most prominent spaces in the new building,” says Ken Johnson, executive dean and chief medical affairs officer. “Our campus dean is collocated in that space now as well. It’s a visible commitment to the work.”