In 2021, the U.S. Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), allocating $550 billion to help improve and modernize the nation’s aged and crumbling infrastructure. That this measure moved forward at all in today’s polarized political climate is a triumph; it’s a sign that unity is still possible when the stakes are high enough. And the bill makes historic investments in public transit, rail, clean energy, and electric vehicle infrastructure—all elements that are vital to the future prosperity of the nation. Yet, the bill could go even further to incentivize mass transit, reduce the climate impacts of transportation, and rebuild transit-adjacent communities that have long been underfunded or ignored.

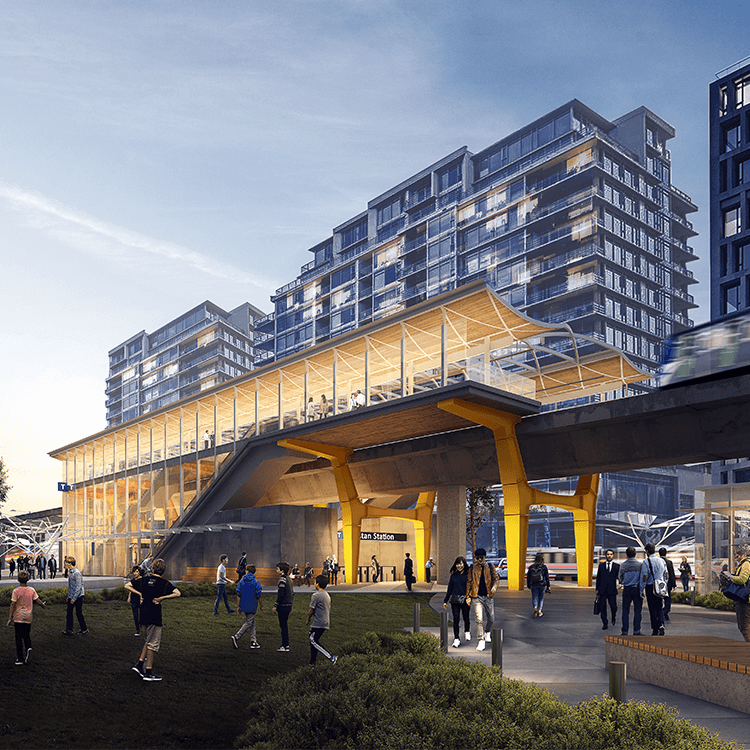

The question then becomes, what happens next? Given the pace of infrastructure rollout, it’s not too late for America to make the most of the IIJA. That will involve a shift in perspective—not just viewing infrastructure as a powerful tool in and of itself, but also as a key building block to create something both activists and developers agree they need: better communities.

Fortunately, America may not need to look too far for inspiration. In 2016, its northerly neighbor launched the Investing in Canada Plan (IICP), allocating more than $180 billion over 12 years for federal infrastructure. (This is a huge investment, considering Canada’s population is about one-ninth that of the U.S.) Despite similar hurdles within the Canadian government’s bureaucracy, the IICP—unlike the IIJA or the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act—has made a concerted effort to grow the country in a sustainable and equitable way. Not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because it makes the most financial and practical sense, particularly in the context of building effective places.