Ralph Johnson: Pure Designer

It can take a decade or more to establish oneself as an architect. Not so Ralph Johnson. Within a few years of his masters and arriving at Perkins&Will, he was already working shoulder to shoulder with practice leaders and winning the industry’s most coveted honors.

Today, more than four decades later, his portfolio features hundreds of projects, many of national and international renown. He is one of the United States’ most celebrated architects. In 2022, AIA Chicago recognized him with its Lifetime Achievement Award.

A celebrated designer in his own right, Jerry established himself working alongside Ralph on many of the award-winning projects of the 1990s. “There were people who excelled in various roles, but Ralph is a pure designer,” Jerry explains, adding that his mentor could easily have claimed a rightful place among his starchitect peers.

An unusual brand of ambition never compelled Ralph to stand apart from his colleagues, however. In fact, for many, Ralph Johnson and Perkins&Will are synonymous—it is hard to imagine one without the other. Their legacies are now bound together.

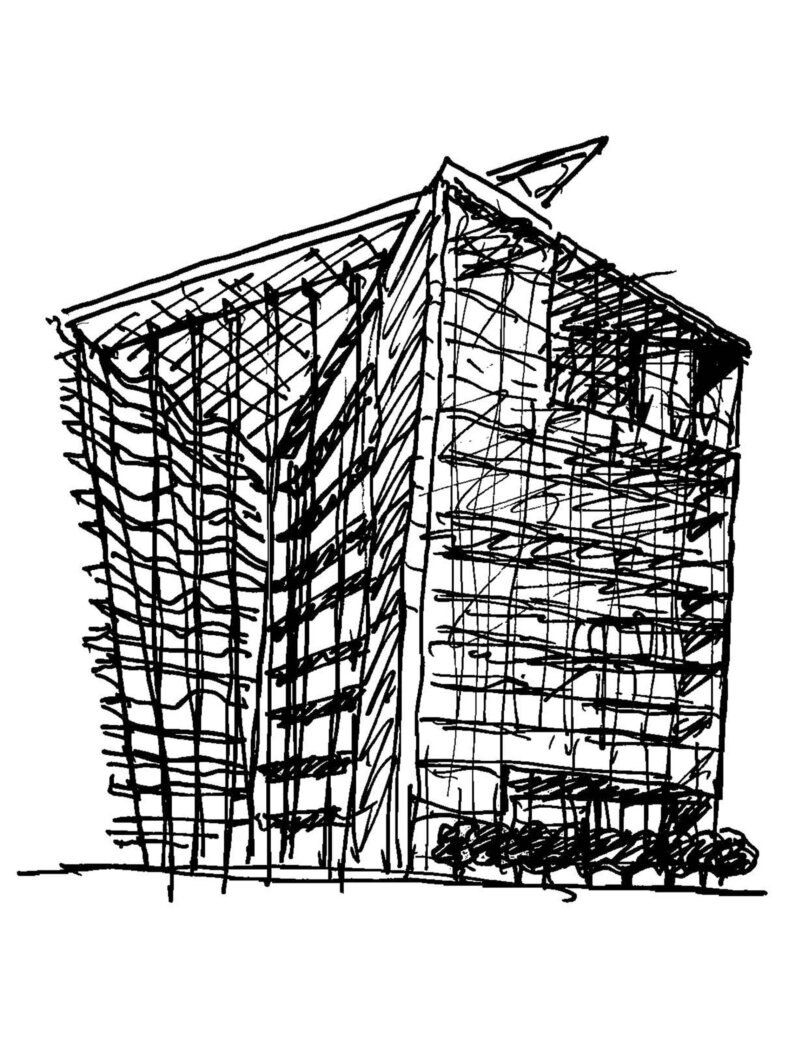

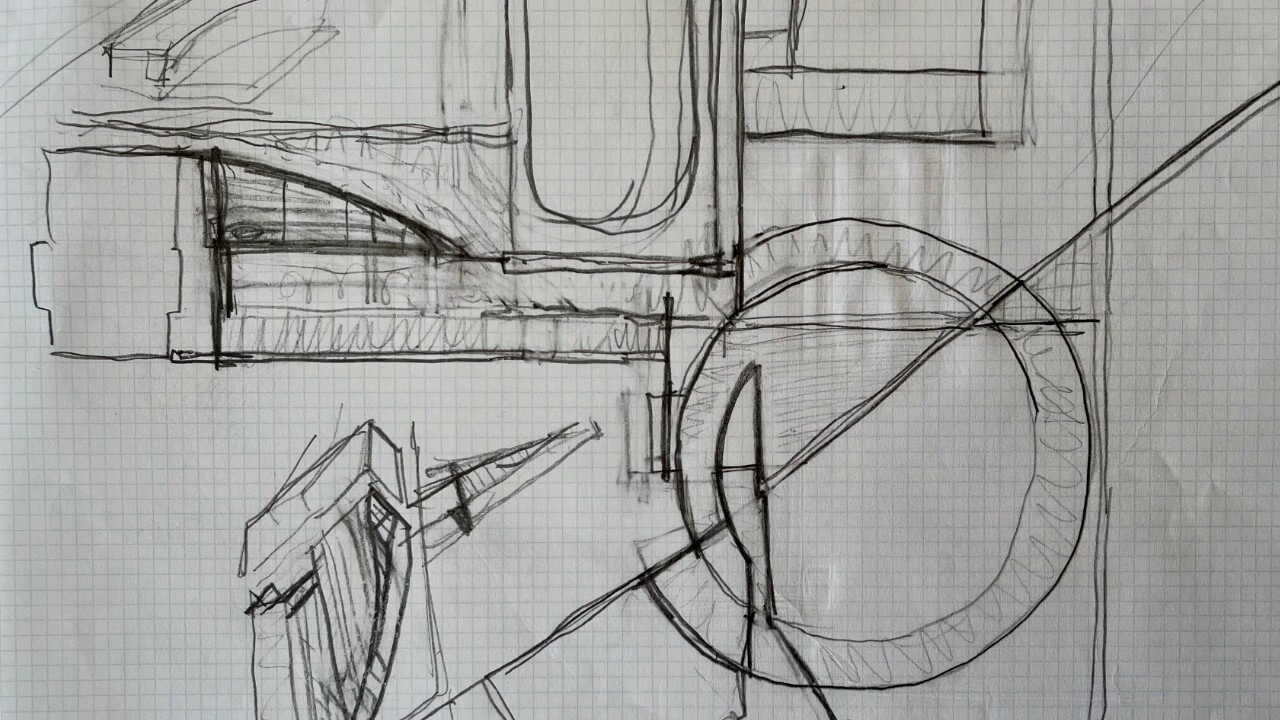

Some of Ralph’s signatures are in his method. Gina Berndt, a colleague since she joined the Chicago studio with The Environments Group 15 years ago, remembers her first impression: “I could see his personal nature, sketching away. He sits quietly in a crit or when looking at someone’s work. Then he can just immediately edit with such clarity of thought and precision.”

Other signatures are in his character. “He has a way of taking notice of things around him that others don’t immediately perceive,” Gina says. Over time, she has also discovered Ralph’s wit. “He’s got a way of reading a situation and making a quick comment,” she adds. “You don’t expect him to be so funny.”

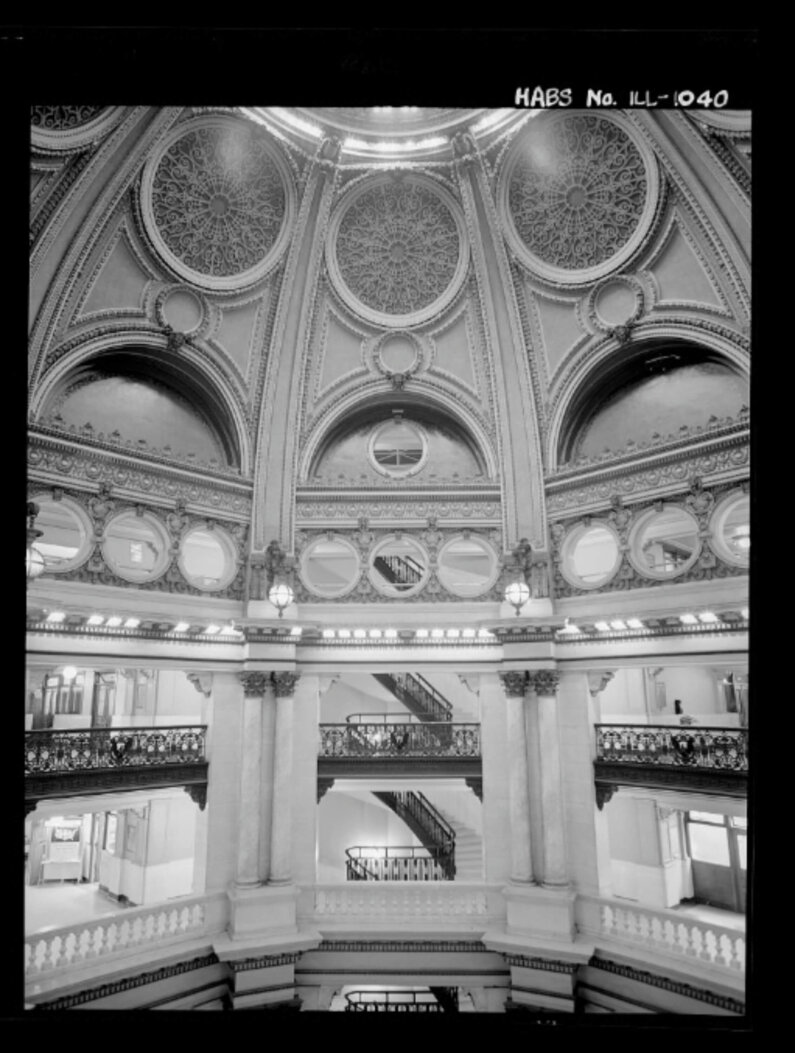

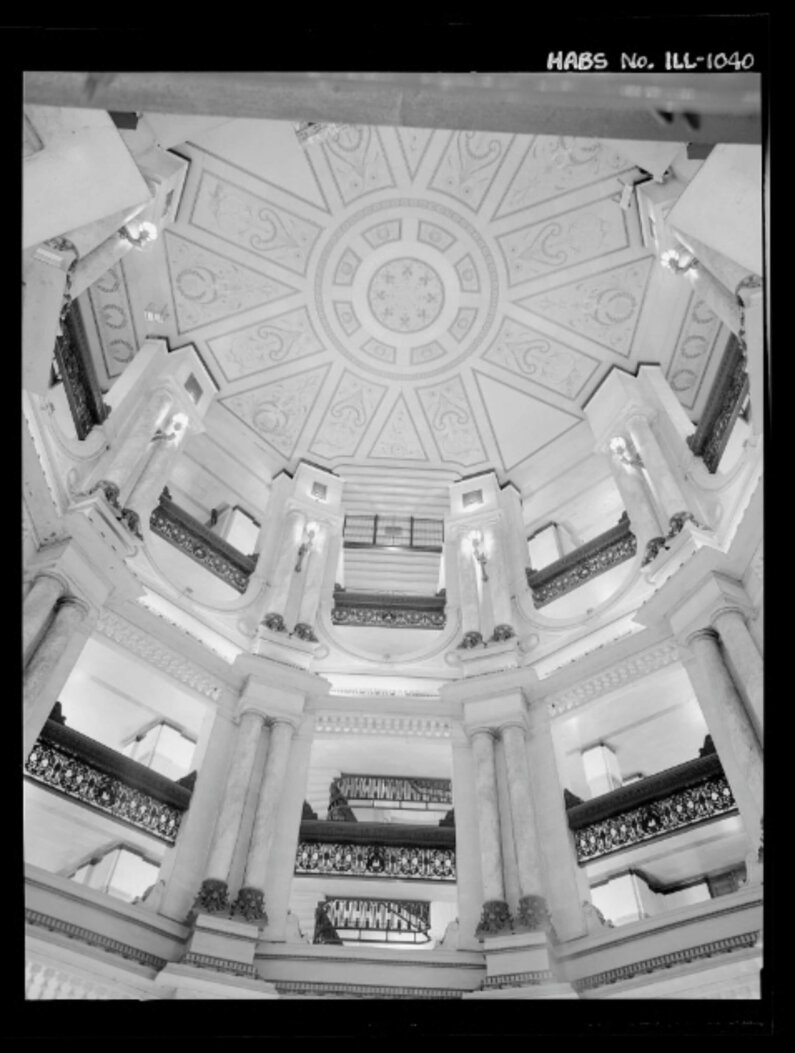

Placing a high value on context, local materials, and American craftsmanship, the Prairie School believed architecture should be born of its environment. Perkins&Will co-founder Dwight Perkins was in the movement. Frank Lloyd Wright was its best-known practitioner.

As it happened, Ralph grew up down the street from Wright’s R.W. Evans House on Chicago’s South Side. He recalls noticing that the house seemed especially alive: “The other houses next to it were just sitting on top of the ridge in a static manner, and this one was projecting out and grabbing the site, engaging the site in a different way.” Ralph has since built his career out of re-creating that vitality in his own designs.

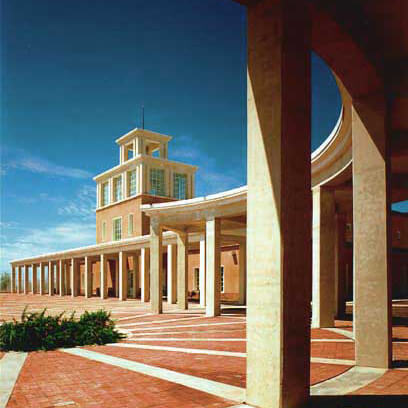

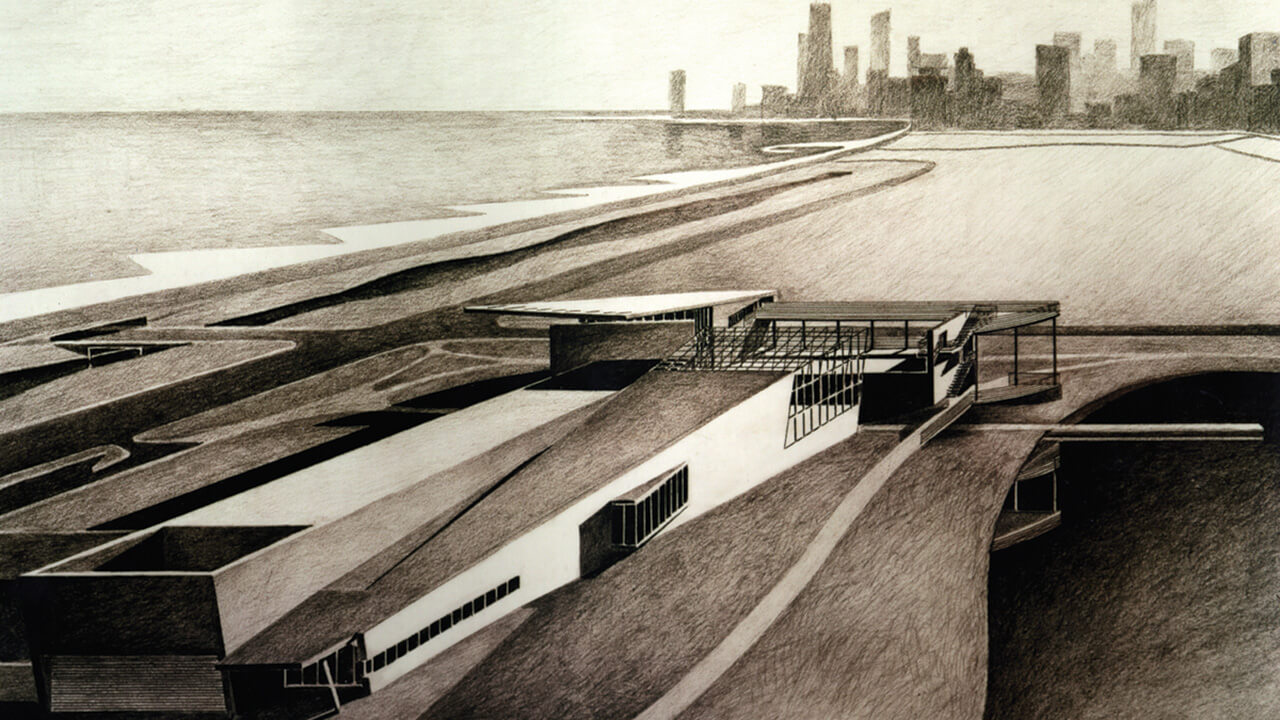

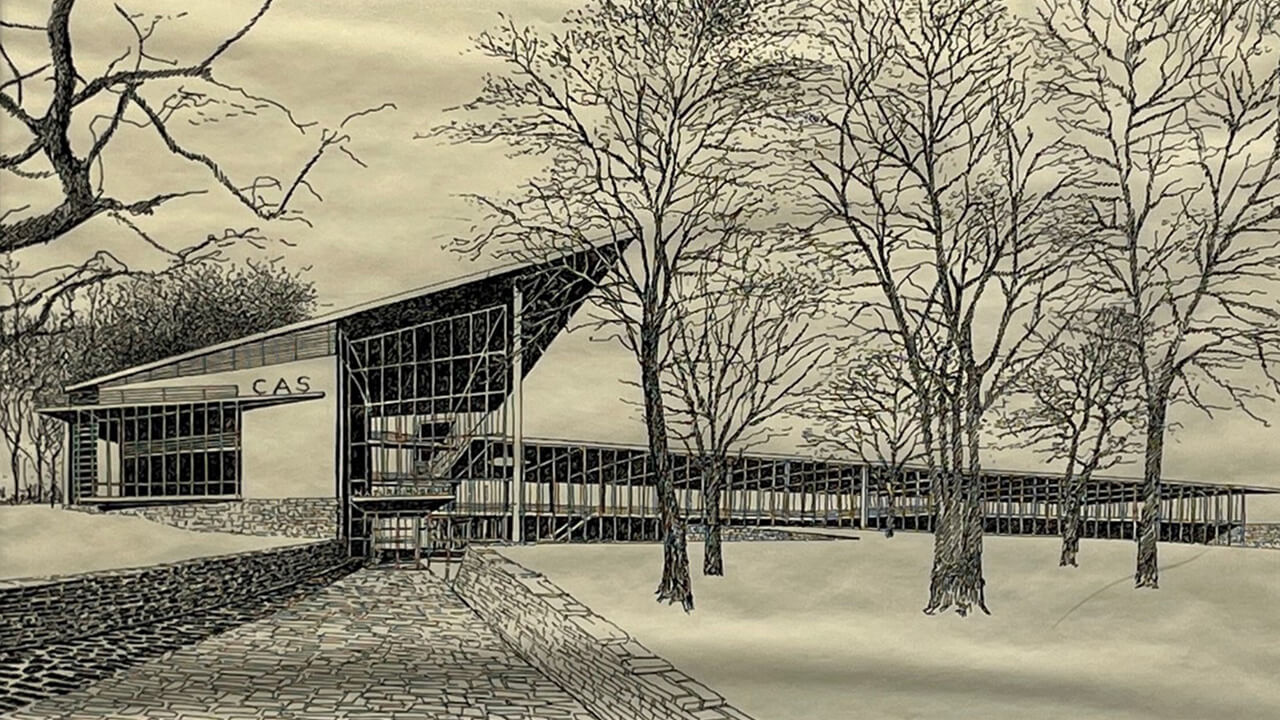

Carl Knutson, design director of Perkins&Will’s D.C. studio, singles it out as a favorite. “Low to the ground” and “thoughtfully integrated into the site,” the building dissolves some of the most conventional physical boundaries—between indoors and outdoors, between ground, floor, and ceiling. The resulting openness draws people along the expansive views of the sky and nearby cultural institutions such as the Cleveland Museum of Art. And that was, after all, the brief: to bridge the separation between the university’s two historic campuses, creating a connector and a destination for the community.

The Center does stand out on campus, but its grandeur does not outshine its neighbors. It elevates the conversation within and among campus spaces, a built expression of its educational purpose.

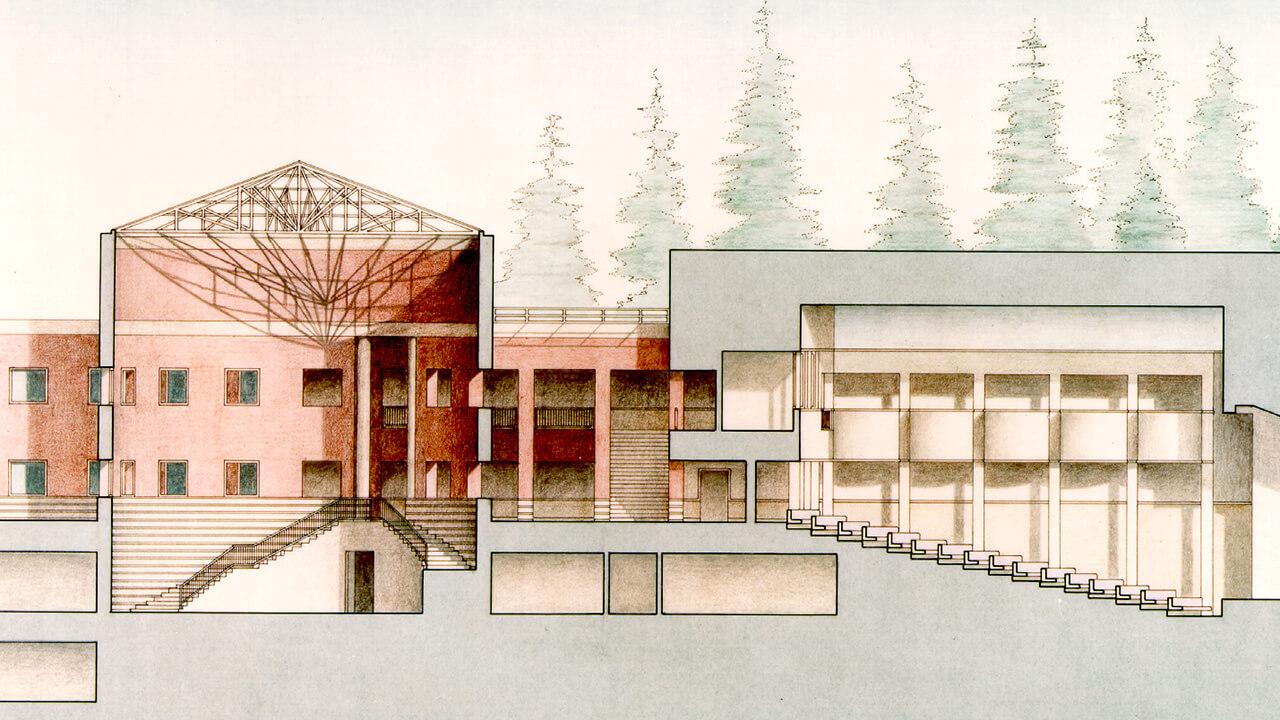

When Ralph joined Perkins&Will, the firm’s only studio was devoted almost exclusively to healthcare projects. Then in the early 1980s, demand for school buildings cycled back. “I guess I was in the right place at the right time,” Ralph says. He began designing K–12 schools with Bill Brubaker, who had been keeping up with industry trends.

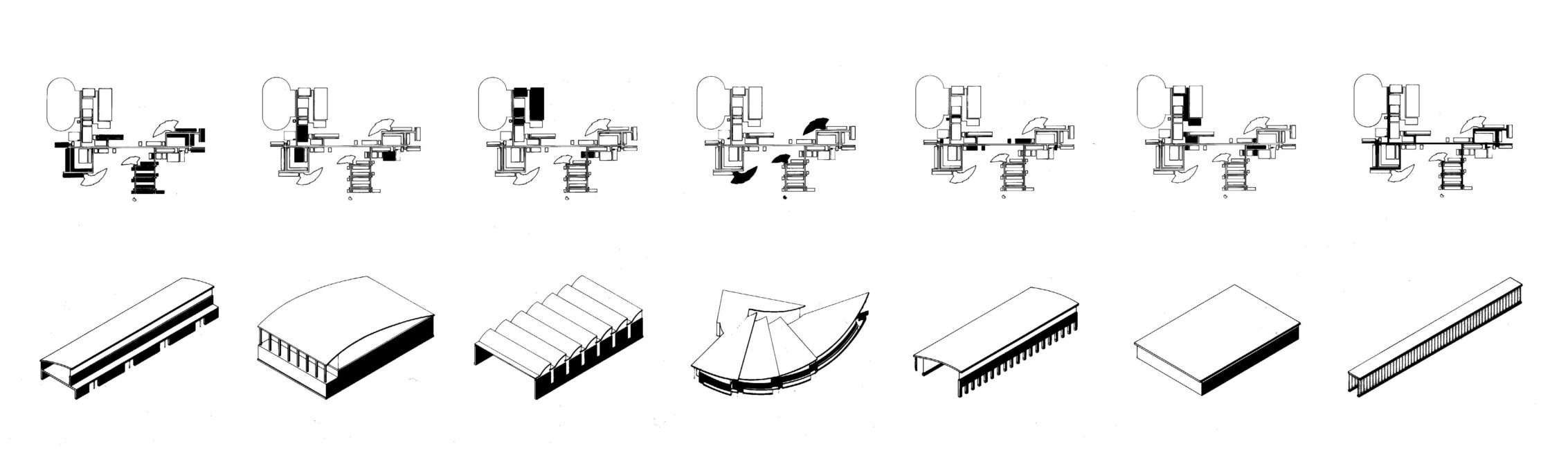

Over the next decade, with Bill planning and Ralph designing, the two architects reinvigorated Perkins&Will’s legacy of innovative school design. Their collaboration lent itself to a “kit of parts” scheme, and Ralph put his Prairie School influence to work playing with regional materials and forms. During this time he evolved the approach that would later produce closely tailored responses to site and context such as the Tinkham Veale University Center.

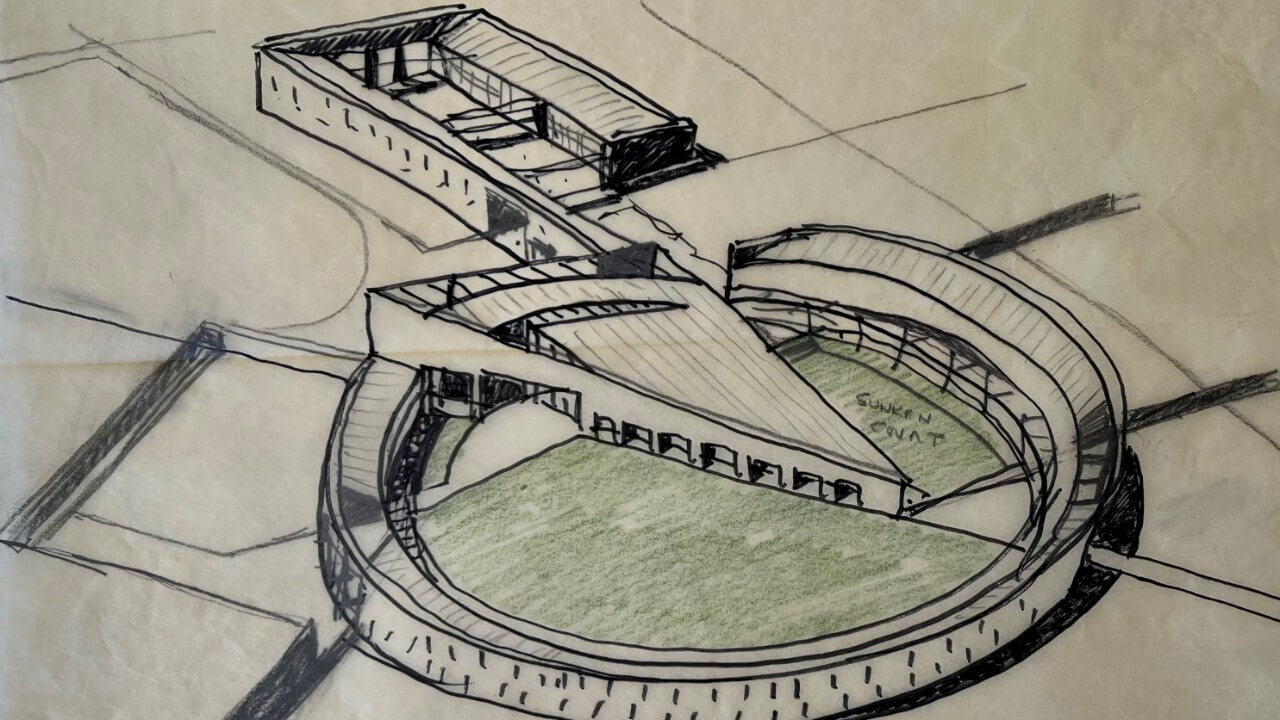

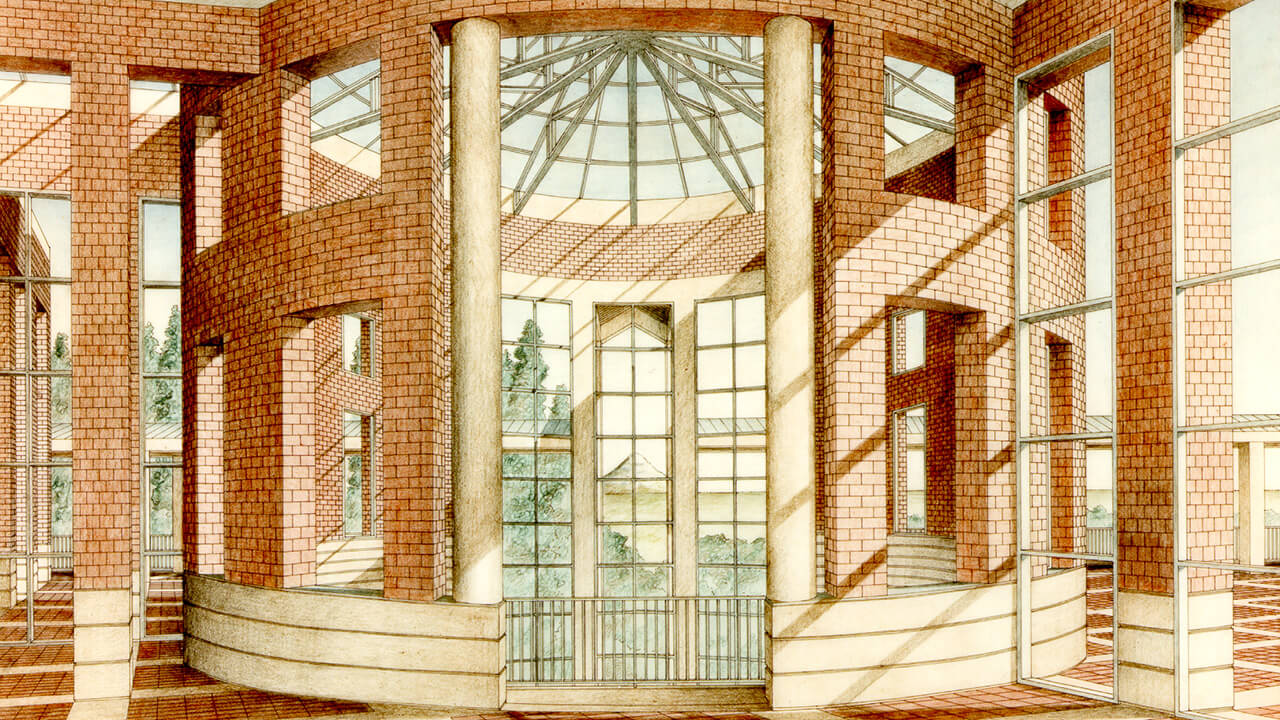

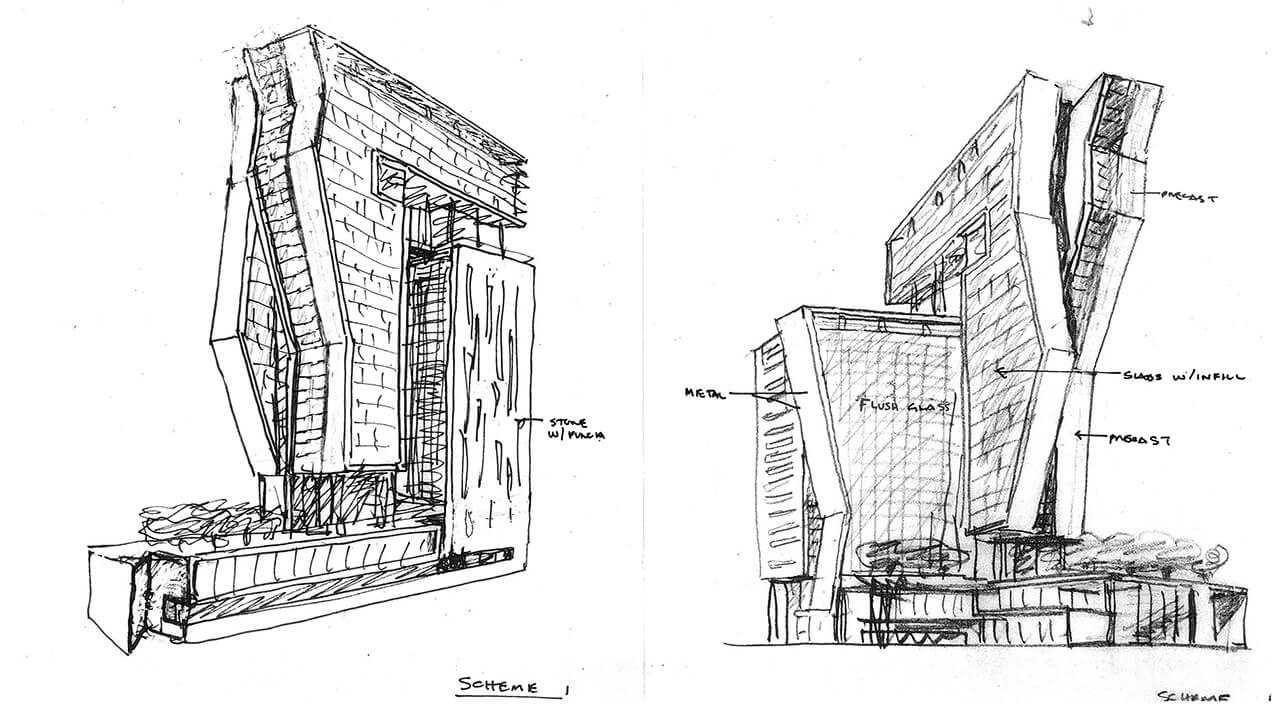

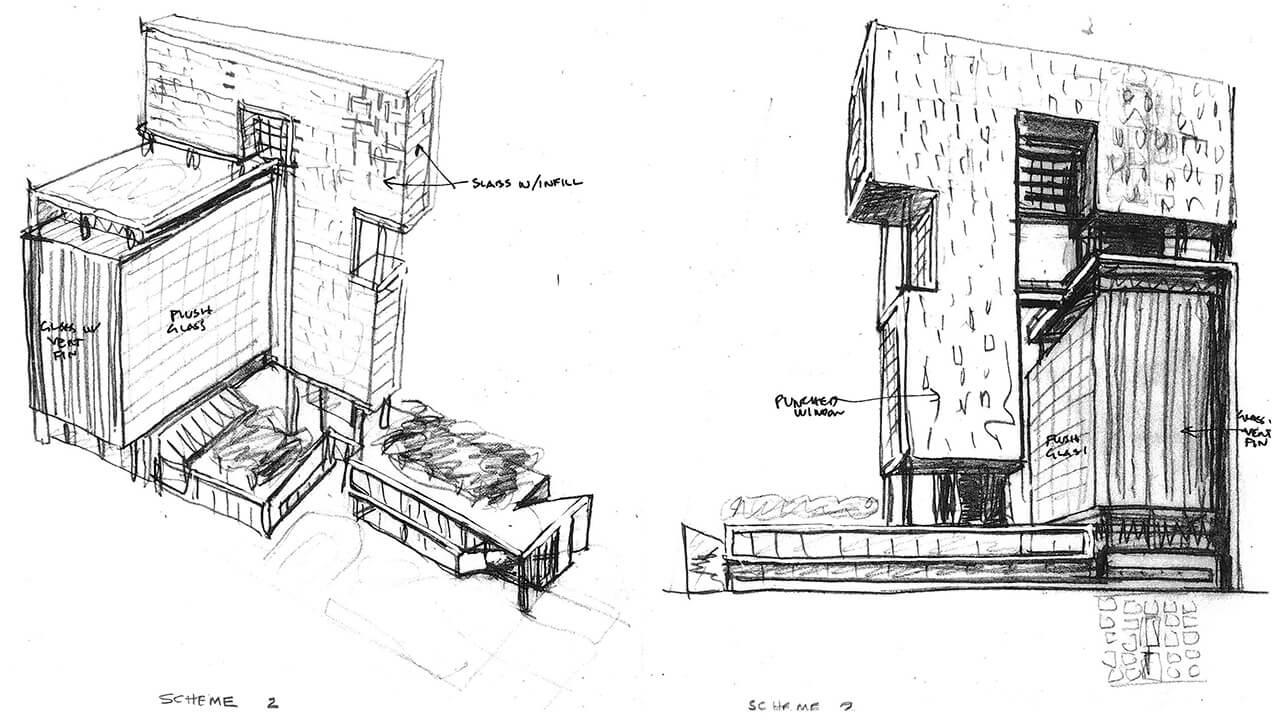

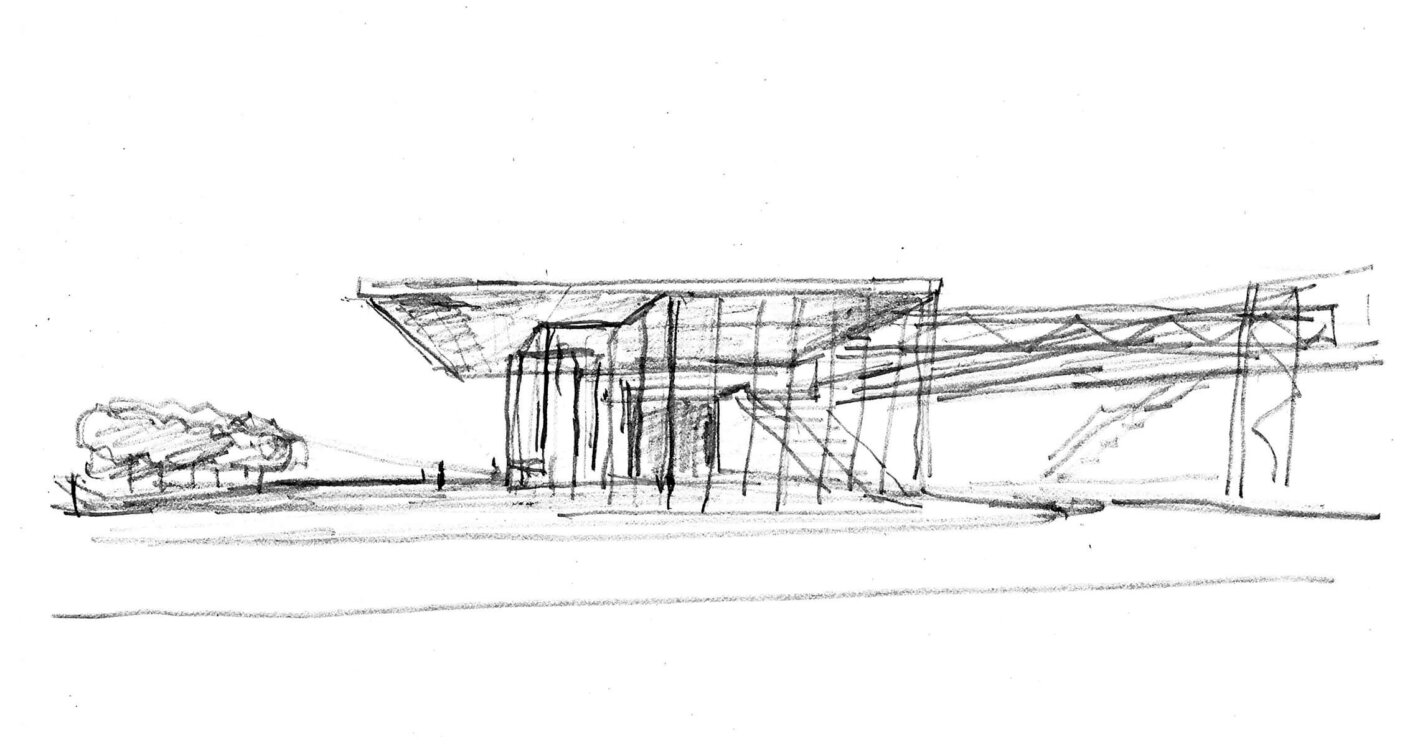

“It doesn’t strike like lightning,” he says. “You learn through experience and struggling.” Of course, architecture is necessarily iterative, and architects are always up against the clock, so Ralph is an obsessive sketcher. He starts inside, with the program and planning; then he turns to the outside. His process consists of “working back and forth, inside again, outside again, thinking about the interior and then the exterior at the same time.”

That is why the drawings are powerful, says Steven Turckes, Perkins&Will’s current primary and secondary education practice leader—because “Ralph designs in sketch form.” The drawings are two-dimensional, but the idea is three-dimensional in his head.

“Some designers are very plan oriented,” Steven explains. “They’re figuring out the floor plan and then think, ‘OK, let’s figure out what that means when it goes vertical.’ Ralph has got all of those axes happening simultaneously.”

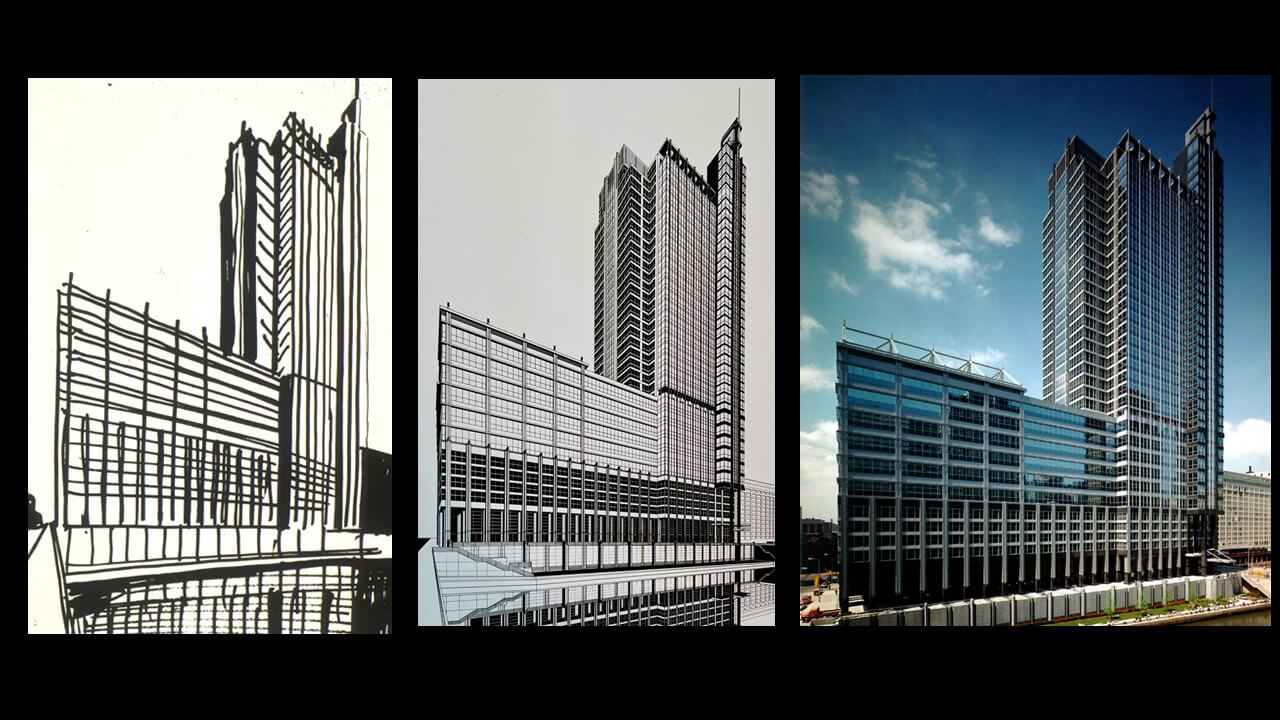

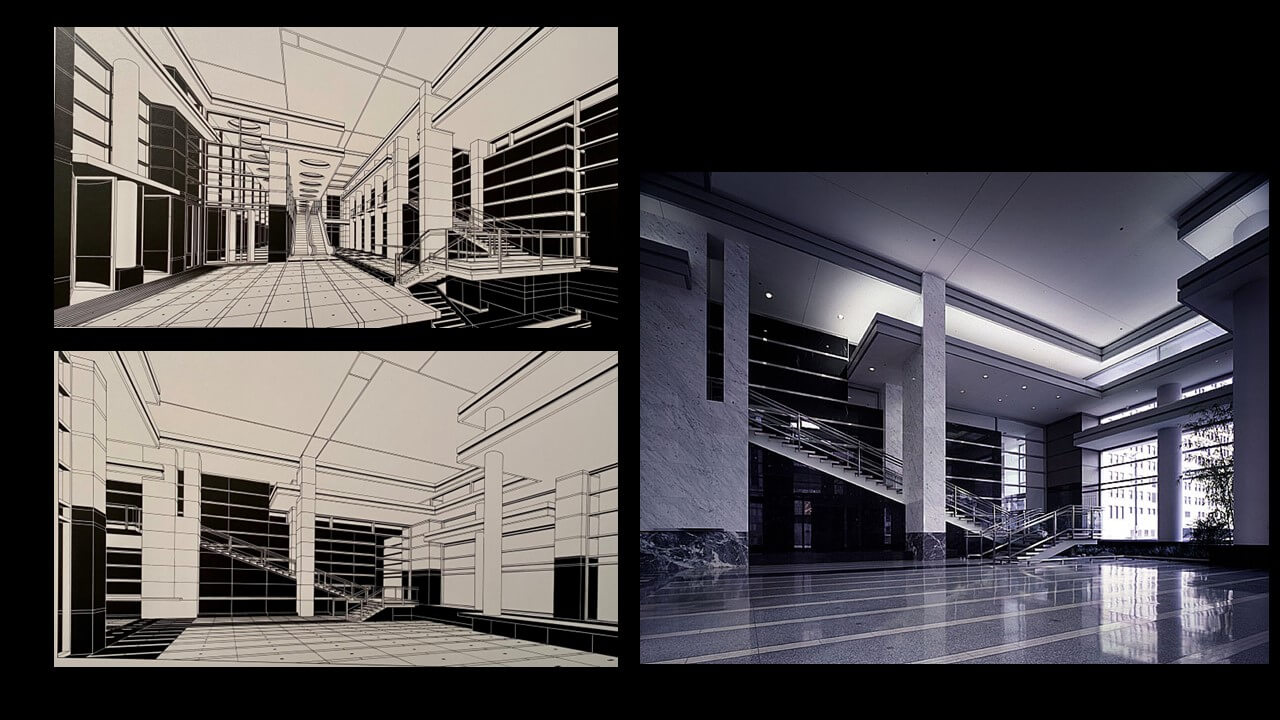

Though not, strictly speaking, a groundscraper like the Kenya Women’s and Children’s Wellness Centre, the Rush University Medical Center triumphs from the same careful understanding of how the building type needs to work on its particular site, wedged between Chicago’s Eisenhower Expressway and the remainder of the Medical Center’s campus.

As with the early groundscrapers, the kit-of-parts approach proved critical. “We didn’t force the technology to do something it didn’t want to do,” Ralph says of the inside-outside process. “We followed strict rules for the design of healthcare and then worked with those to create the architecture and sense of place, scaling the building down into humane environments.”

Hospital functions were divided between a square base, housing “onstage” operations, and a curvilinear “butterfly” tower, housing patient beds. The base then responds to the expressway with a billboardlike façade while the tower engages the campus with greenspace, courtyards, and circulation areas.

After more than four decades of consistent design excellence, Ralph shows no signs of reining in his imagination. Projects and prospects on multiple continents, in cities across the U.S.—and at home—are keeping him fully engaged in the currents and challenges of designing the built environment.

Asked recently by Bryan Schabel, his successor as design director of the Chicago studio, whether there is a building type he has not yet designed, Ralph quickly replied “a spiritual structure.” It seems the thought of what to do next is never far from his mind.