Teams of diverse architects and designers are essential for creating inclusionary places across the world. After all, diversity and inclusion are where creativity thrives. But we all know they can’t do their job alone; they depend on any number of partners and subconsultants.

Now imagine what inclusive design could look like if architects and designers prioritized partnering with diverse collaborators to help bring their vision to life: From design concepts to lighting and acoustics to exhibits and landscape, every element of placemaking would be informed by a potpourri of creative input. Clients would get more innovative design solutions from a team that aligns with their values: According to the Urban Land Institute, 92% of real estate companies prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion. Meanwhile, as investors continue to make ESG (environmental, social and governance) a priority, having teams with varied perspectives behind one’s projects can create a compelling story for the social aspect of their work to attract more investor attention. Clients would also enjoy cost savings—potentially up to 8.5% year-over-year, according to research published by McKinsey. Clients may even be more competitive in attracting and retaining talent, since recent data suggest that 80% of workers prefer to work at companies that are committed to equity and inclusion.

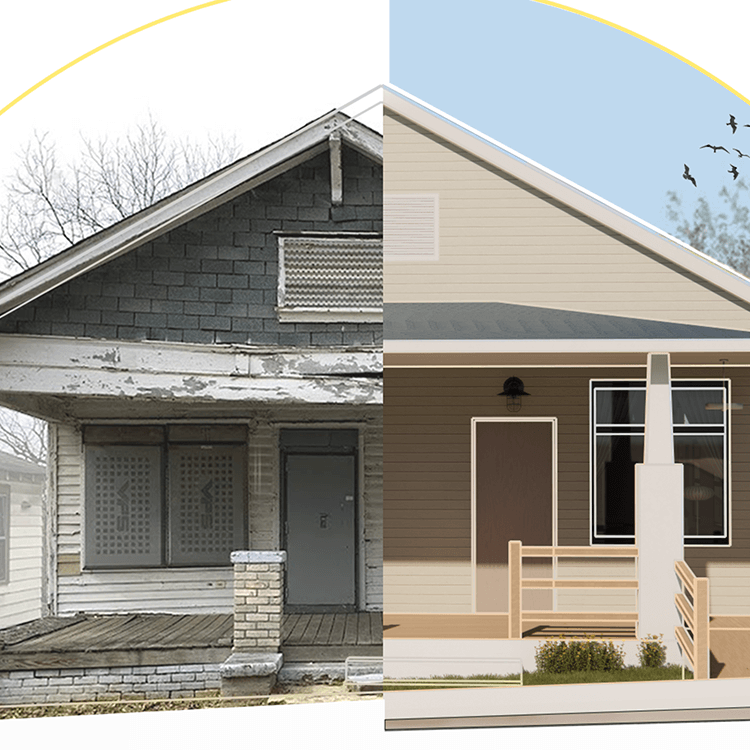

At one of the world’s largest and most established architecture firms, intentional co-creation with myriad partners and subconsultants is a matter of course. Designers from Perkins&Will collaborate closely with women- and minority-owned business enterprises (WMBEs), building enduring relationships, creating opportunity, and enriching the collective human experience. Here are the stories of two recent projects that are raising the bar on inclusive design through co-creation: