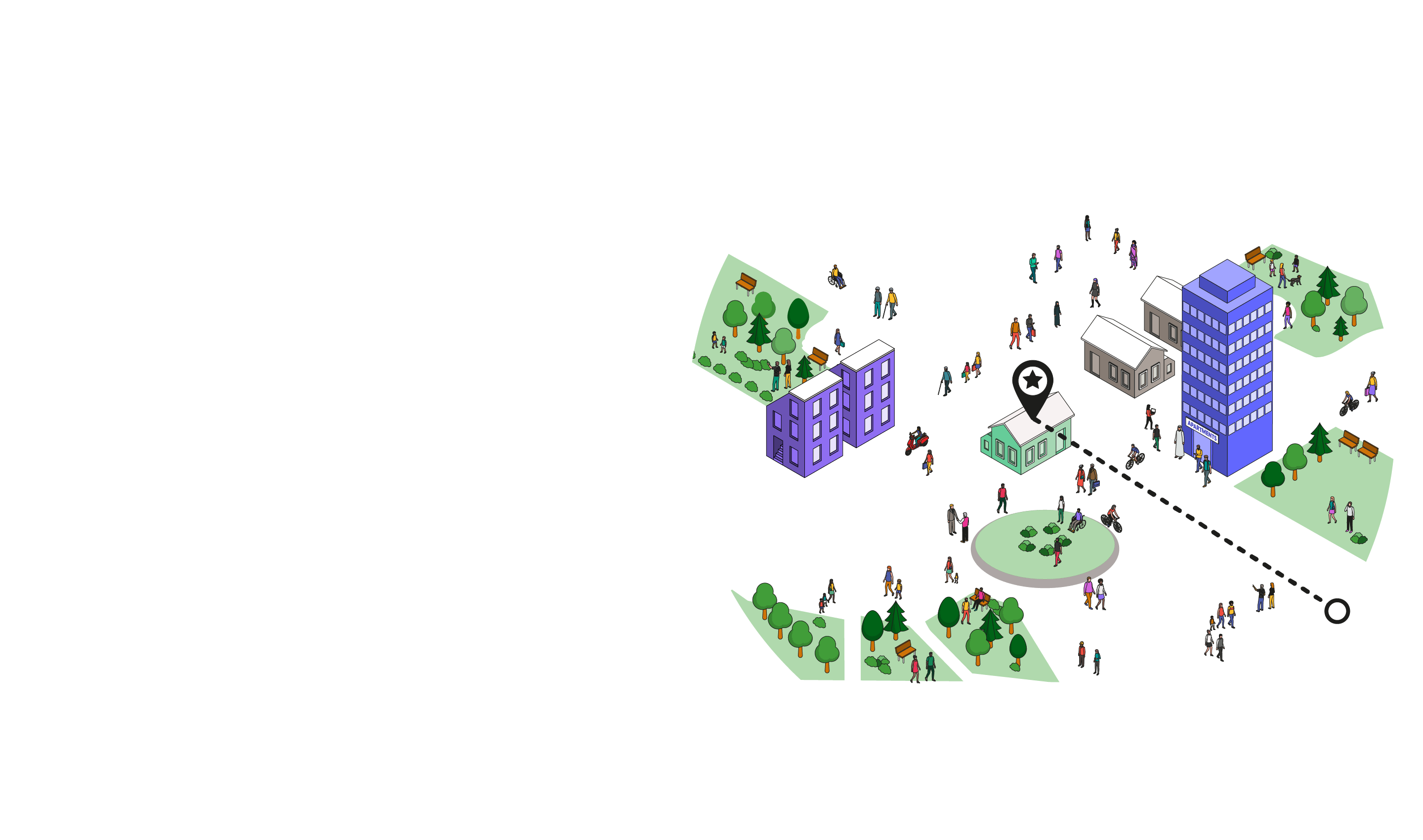

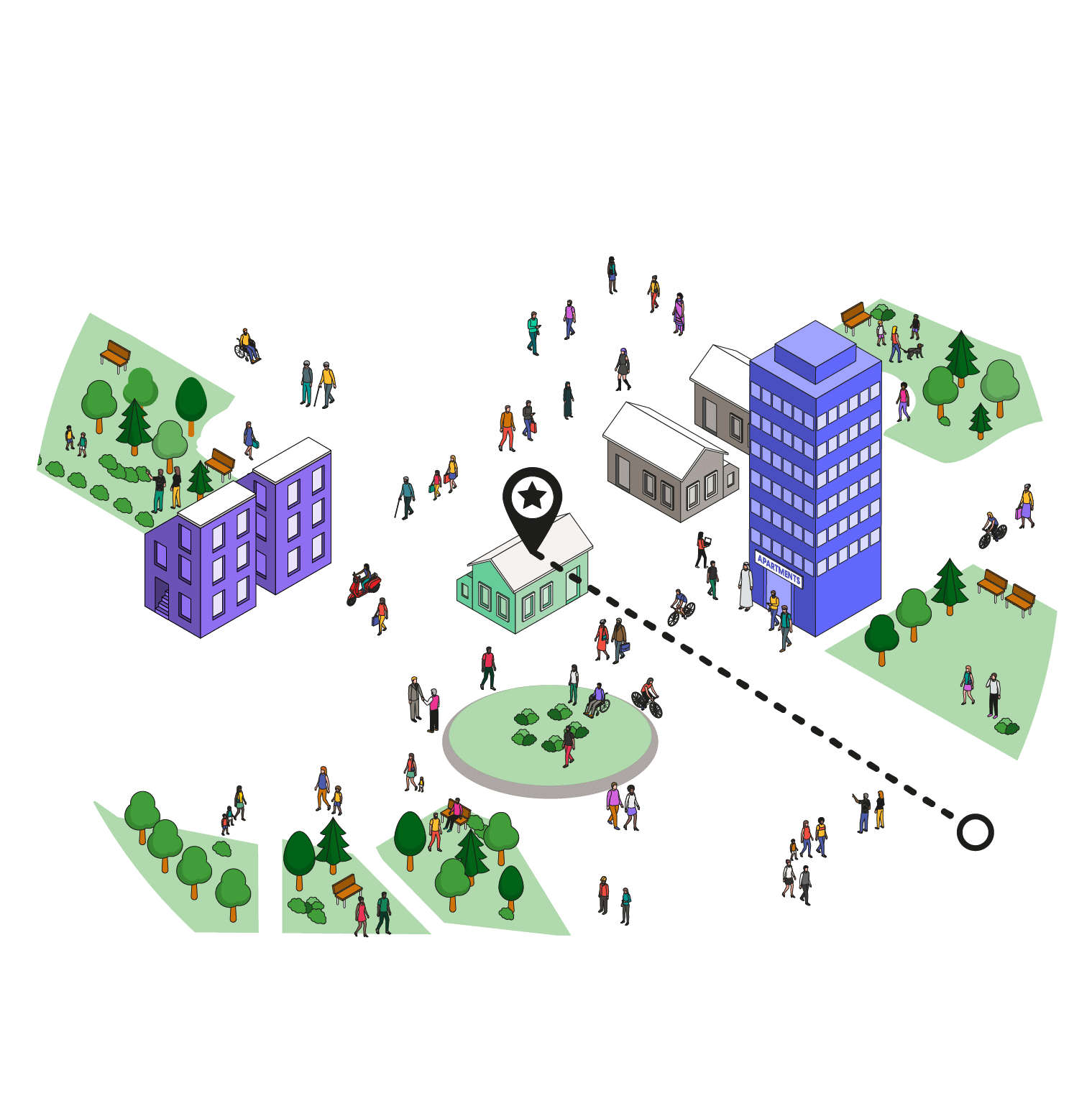

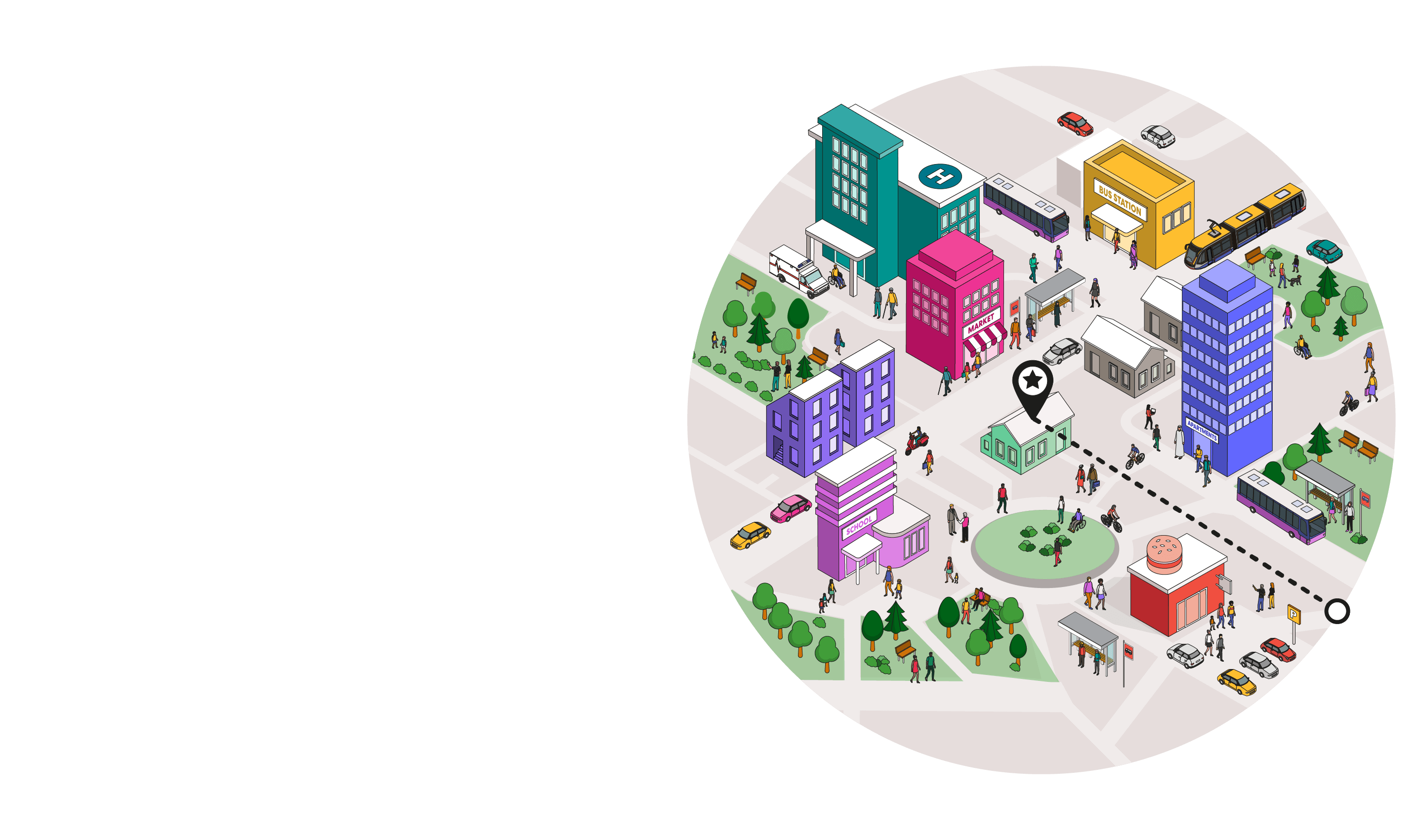

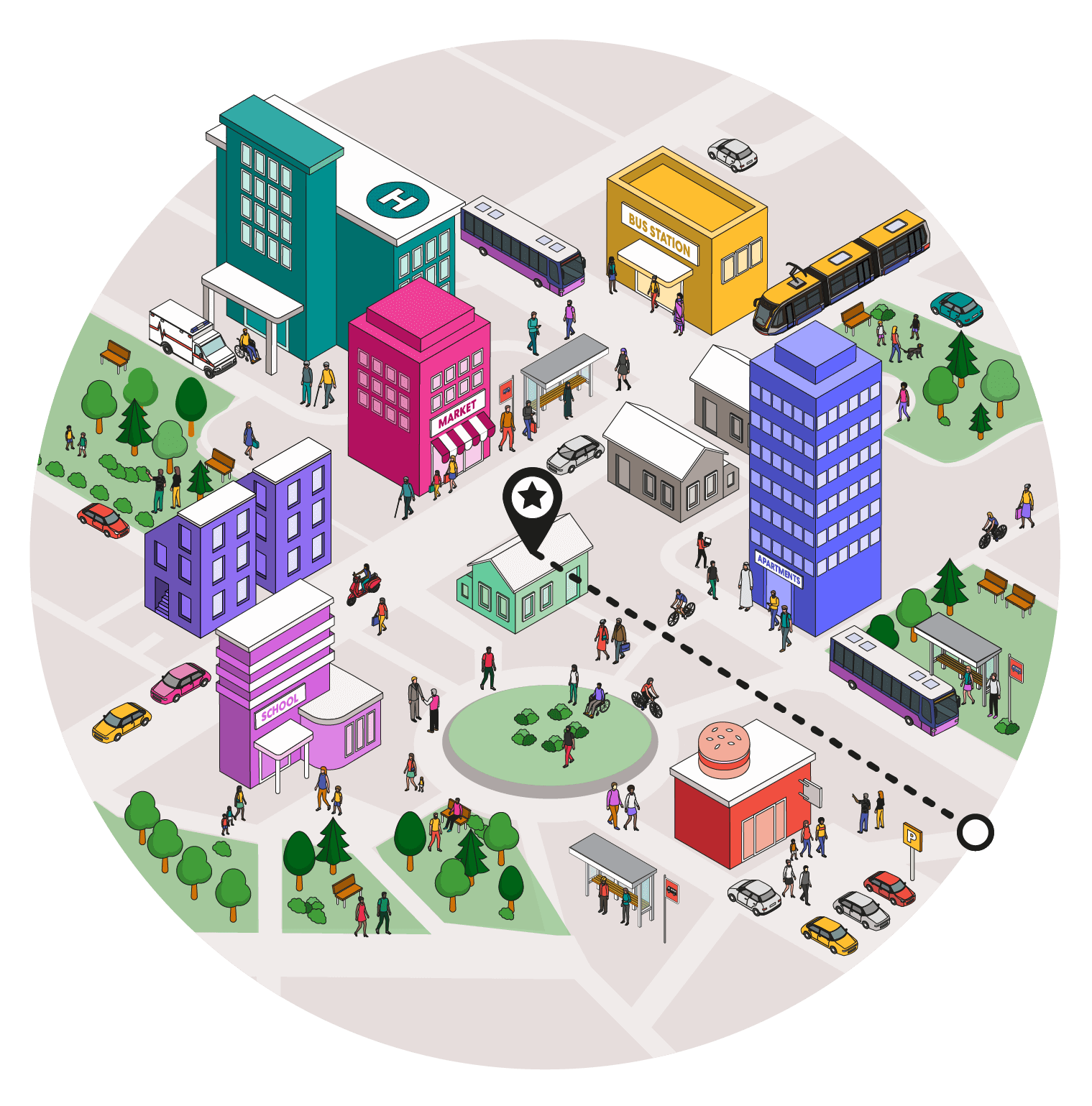

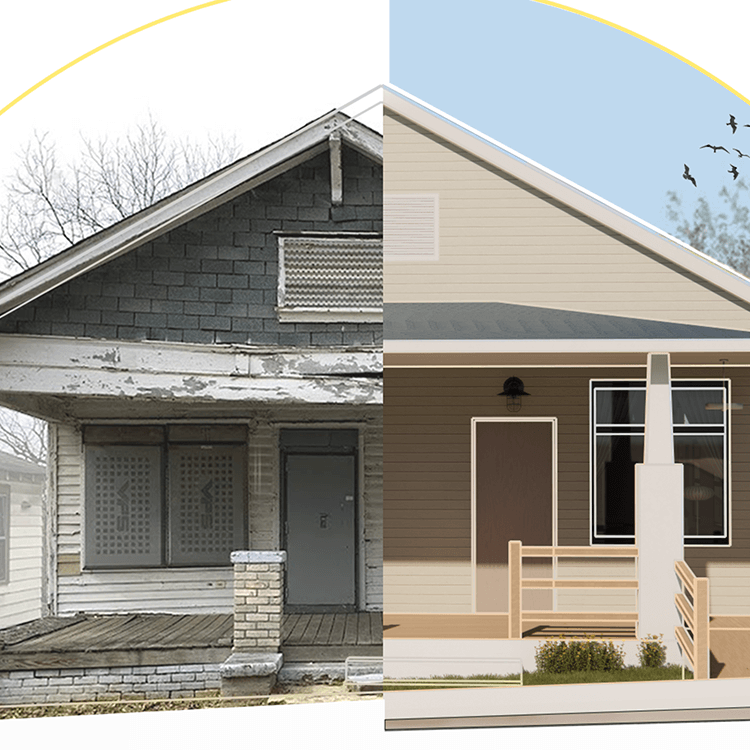

It used to be that density was the key to urban design because local resources and transit can serve a condensed, highly populated community more sustainably than a sparsely populated, sprawling one. But we now know that equity and livability are equally as important, if not more. Healthy, thriving cities aren’t just dense metropolises; they’re vibrant ecosystems that welcome, support, and serve everyone. And the way they’re designed—from the length of their blocks and the width of their sidewalks to their proximity to transit, healthcare, education, food, and open space—is critical to their success.

But the common metrics many urban designers rely on don’t even begin to address the reality of a neighborhood and the people who call it home. While density is still a key factor—it tells us where to build a project and for what purpose—equity and livability need to take priority.

In 2019, I set out to conduct a little experiment. I teamed up with a fellow urban designer to review the typical process for evaluating neighborhood-scale projects. We found that project teams seek answers to important questions about design, but they don’t necessarily ask questions like, “Who lives here?” or “What’s life like for the people who live here?” From a historical point of view, this kind of limited data-gathering has contributed to discriminatory practices that still exist today, like redlining. That alone is a compelling enough reason to change the urban planning process, if you ask me.

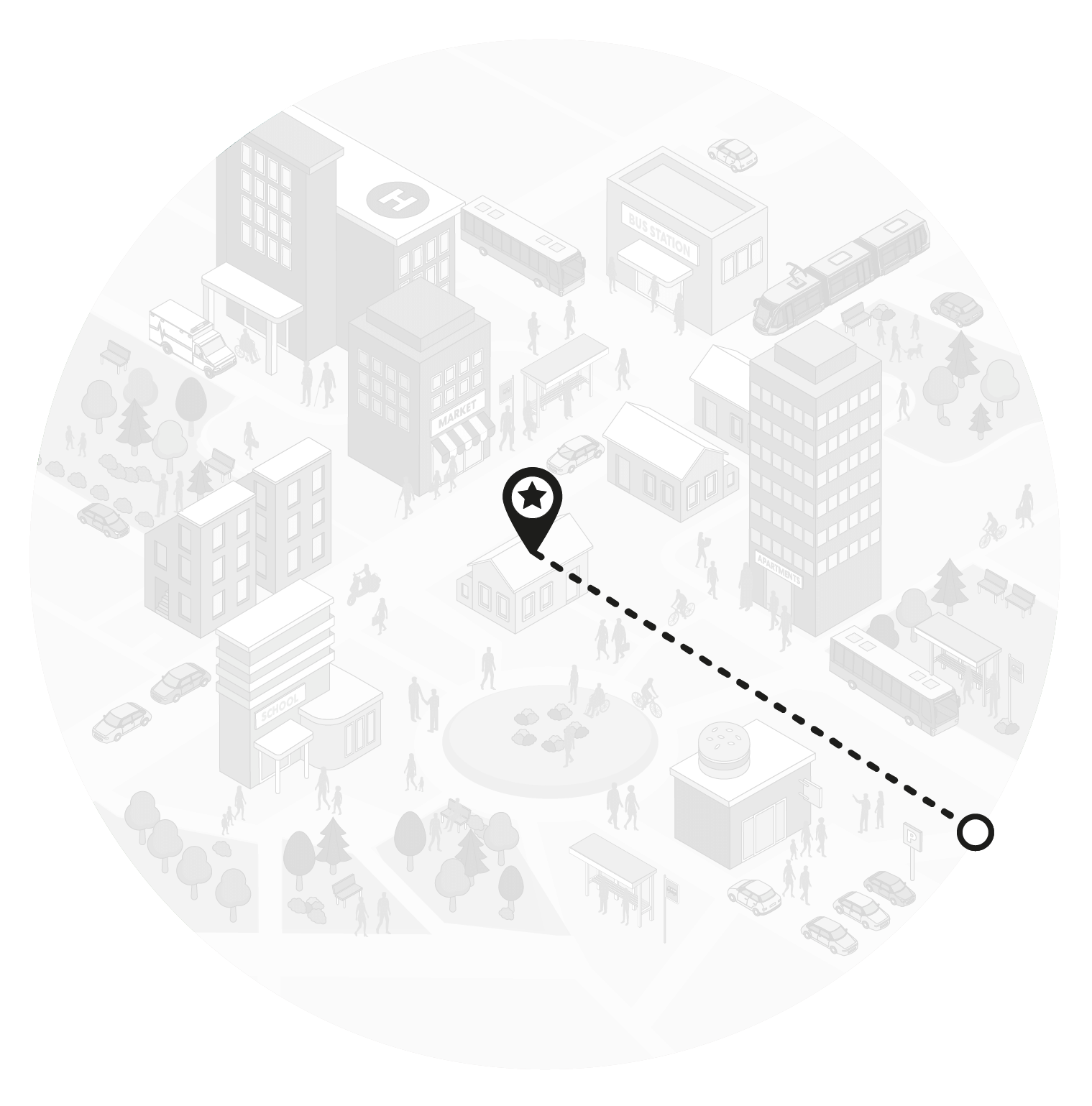

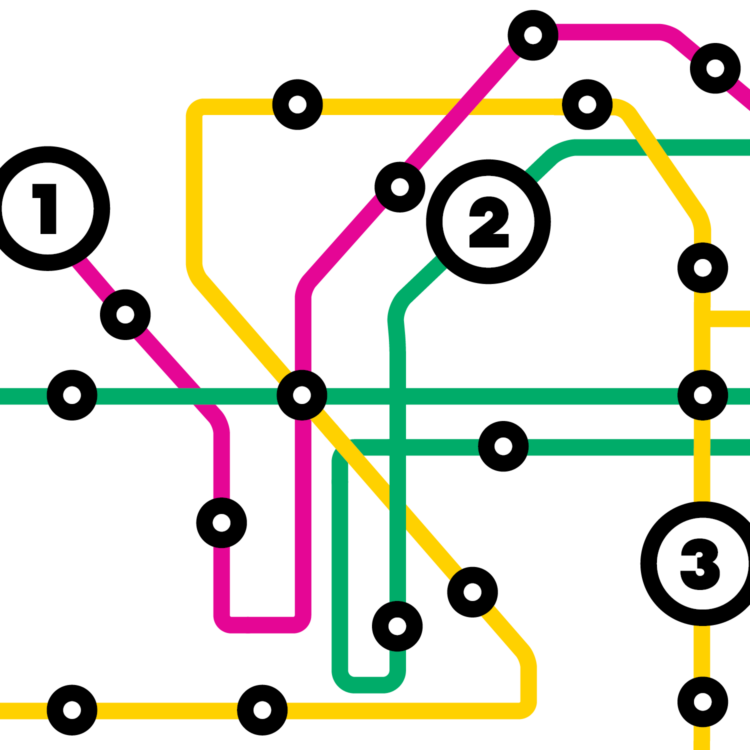

Here’s another reason: Urban designers are often looking for ways to cut car use and encourage people to take public transit, bikes, or other modes of mobility. This makes good sense because cars pollute the air and release an enormous amount of carbon emissions. And yet, what’s often overlooked is the fact that many low-income families rely on cars to get to work, go to school, visit the doctor, or reach the nearest grocery store, often because their neighborhoods were designed without walkable access to these resources. In cases like this, a new development that removes street parking can cause added hardship for families who are struggling to get by.