Susan Ealer is a Senior Medical Planner and a Documentary Filmmaker. She is based in New York City but maintains roots in L.A.

Susan Ealer is a Senior Medical Planner and a Documentary Filmmaker. She is based in New York City but maintains roots in L.A.

First, the setting:

New York, NY: The epicenter of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Perkins&Will architects and planners scramble to create desperately needed space for beds as 500-800 people perish every day.

Los Angeles, California: A potential hot-spot as the rolling epidemic sweeps the country. Perkins&Will designers look to solutions for homelessness, one of the longest standing pandemics in the country, to inform designs addressing COVID-19.

Now, the story:

New York

It’s a freezing day. I’ve just returned to my “stay-at-home” office from a long drive across the Hudson River in an ice storm—a thwarted appointment to get a COVID-19 test at a pop-up testing site. The pop-up wasn’t there—just an empty parking lot with other desperate people like me, wearing masks and driving in circles. Apparently, not enough health care workers showed up to help that morning.

My phone rings. The ID says, “Mark Tagawa, Associate Principal,” one of the Senior Designers in our L.A. studio. It’s early for a call from L.A.— not even 9am Pacific time. It must be important. I pick it up.

Mark heard that the New York studio completed some preliminary layouts for an emergency COVID-19 conference center retrofit and is hoping I can send them. The L.A. studio is developing a surge facility kit-of-parts based on modular homeless shelters they’ve recently designed. They need the latest standards—guidelines that have been tested on the front lines of the pandemic. I send him the layouts I’ve been working on with Chuck Siconolfi, a Principal and Healthcare Design Strategist in our New York studio (and one of the most experienced planners working in healthcare today). It is in this moment that I begin to realize just how powerful national collaboration can be during times of crisis.

In choosing our professions, healthcare architects, planners, and designers take a silent pledge to not only “do no harm,” but also to improve the quality of human lives. Never did any of us think this meant our designs would literally mean the difference between life and death for thousands of people around us. COVID cases were tearing through New York. Hospitals were overflowing. Morgue trailers were starting to line the streets. Dire predictions in the headlines everyday were warning that New York City would soon be short 140,000 beds. This was the reality when the Greater New York Hospital Association (GNYHA) Task Force called Carolyn BaRoss, our Global Healthcare Interior Design Director, inviting our firm to join a coalition of architects, engineers, and builders working under Governor Andrew Cuomo to adapt hotels, conference centers, and nursing homes to provide much-needed hospital beds.

Led by Brenda Smith, Healthcare Practice Leader in New York, our team mobilized immediately. Rob Goodwin, Design Director in our New York studio, donned a mask and gloves and risked his life, literally, by walking with the engineering team through buildings in the heart of the epicenter to assess their viability. From the list of buildings to be adapted, the GYNHA Task Force assigned Perkins&Will the GE Training Facility Campus in Crotonville, New York, about an hour north of the city. The GE facility was chosen for its potential to provide a large number of beds in a well-maintained hotel-like conference center complex.

I met virtually with Chuck and Jason Towers, Senior Medical Planner, to quickly plan a building type none of us had ever seen before. The pressure was on—task-force designs needed to be implemented in a matter of weeks. It turned out we were a good match. With Chuck’s strategic planning experience, Jason’s knowledge of large-scale international healthcare projects, and my programming focus, we came up with innovative adaptive-use solutions quickly. These included turning the GE campus’s large open-plan greenhouse into a triage center and using the dormitory building’s wings and pods to separate patients based on the severity of their illness.

Los Angeles:

It takes me a good, long moment to slow down and adjust to the pace of the thoughtful and beautifully executed drawings sliding by on my screen. They describe a modular surge facility developed by the newly formed L.A. Proactive Response Team, under the guidance of Yan Krymsky, Design Director of our L.A. studio, and David Sheldon, our L.A. Corporate and Commercial practice leader.

I’m attending the L.A. studio staff meeting virtually from New York, along with my L.A. colleagues who are presenting the surge facility project: Tina Giorgadze, Senior Project Designer; Jorge Mutis, Project Designer; and Ksenia Chumakova, Designer. Dialing in from the pandemic’s epicenter, where urgent meetings are being led using hastily sketched drawings and quickly developed Excel spreadsheets, my response to the team’s presentation is mixed. First, I feel admiration, and even nostalgia, for the lovely design sketches I am seeing. But then, from somewhere underneath, I sense dread rising, and the sudden realization that these folks might not really know what is coming for them. I feel an overwhelming need to warn them.

My “warning” ultimately took the form of a presentation that showcased the improvisational work methods we had been using to develop our COVID adaptation projects in New York. The L.A. team mostly benefited from the programming piece, which incorporated planning knowledge we had accumulated on the front lines of the pandemic.

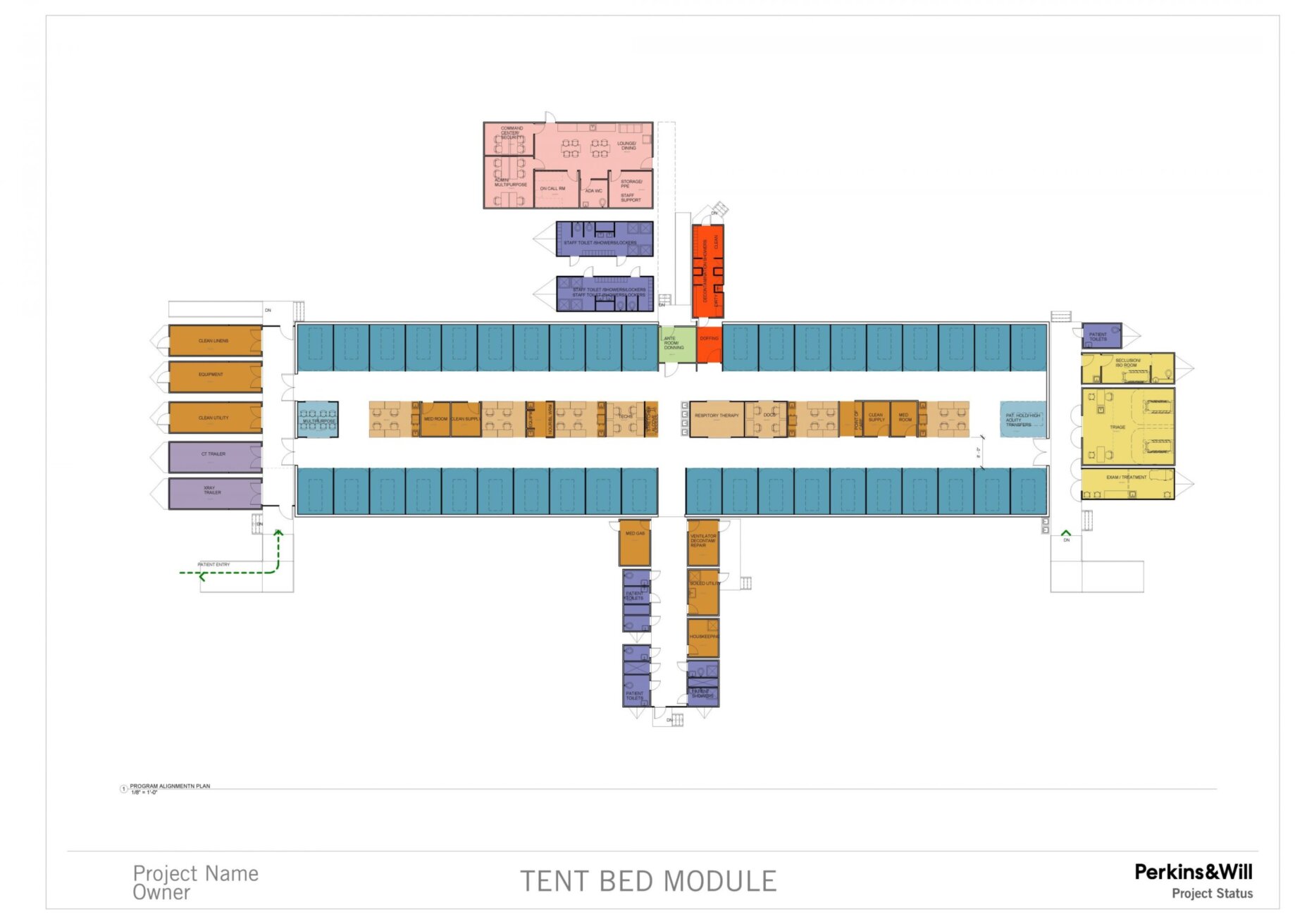

I collaborated closely with Tina, who was putting together the kit-of-parts. Like the interim homeless shelters the L.A. studio had designed for the “A Bridge Home” program, the main component of the COVID kit was a tent that, in this case, would hold patient bays and clinical support. The rest of the kit was composed of a menu of prefabricated trailers, which included various functions: isolation, imaging, decontamination, triage, staff support, etc. The kit offered a solution that is affordable, can be set up in a hospital parking lot or a more remote location, and can be assembled quickly in an emergency.

Tina and I prepared plans and a program for what we call the “Jean Test”— a review by Jean Mah, our firm’s Global Health Practice Leader (and one of the most eminent medical planners around!). We mostly passed. Jean urged us to simplify and standardize the scheme to make it easier for clients to implement.

Finally, the wrap-up:

Shortly after we completed the kit-of-parts in L.A. the tide of the pandemic in the U.S. seemed to change. Due to the implementation of social distancing and shelter-in-place guidelines, the number of COVID cases slowed and the predicted bed shortfalls thankfully never came to pass.

The efforts of our L.A. and New York studios turned toward the future—toward preparedness for the next round of this pandemic, or another one altogether. Our New York studio’s facility adaptation efforts were incorporated into a formal GNYHA Report—a catalog of possible surge facilities that the State of New York will keep close at hand, ready to use if needed. Our L.A. studio’s modular surge facility kit-of-parts is now being offered to health systems throughout California.

The unprecedented level of collaboration that came out of this crisis-driven, virtual coming-together of our bi-coastal studios is important to hold on to. We will all be better for it, our client’s projects will be better, and we will make this world a better place.